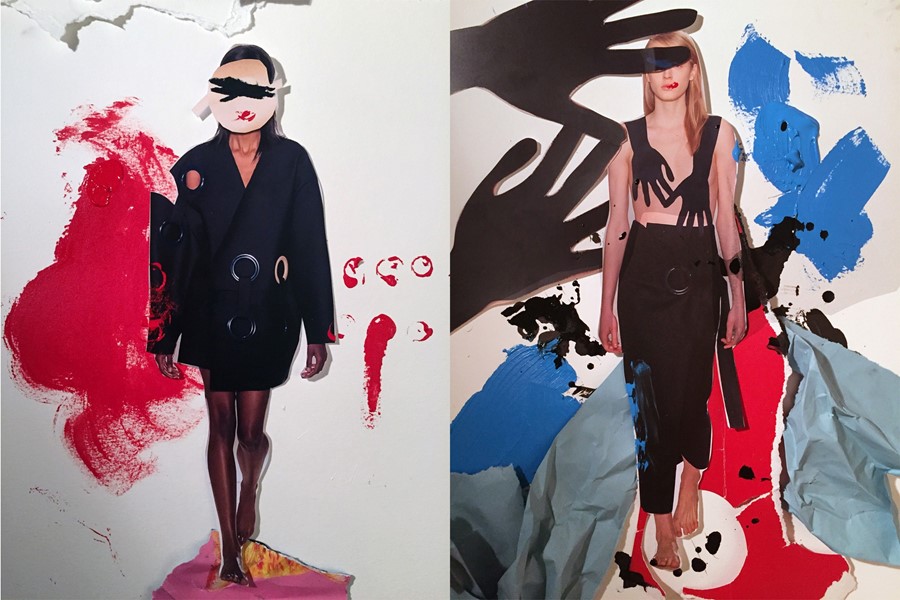

We examine the primitive childhood of Jacquemus A/W15, with collages from Kalen Hollomon and photography by David Luraschi

For A/W15, Parisian designer Jacquemus collaborated with Sebastian Bienek, a German artist who painted the model's faces with kajal and red lipstick to create a disconcerting yet captivating Surrealist illusion on the runway. The impact of the collection can be seen all over social media and fashion press alike, whipping everyone into a frenzy of re-gramming imagery that is simultaneously enchanting and disconcerting. Yet there was something more than a startling visual that could be found in the collection; something more elemental that speaks to an innate innocence rarely replicated with authenticity.

When we spoke to artist Bienek about his collaboration on the collection through the cosmetic application of surrealism, he explained that Jacquemus recently reached out to him to explain that his project "Doublefaced" had inspired the season. And Bienek’s series of fragmented faces was, in fact, originally inspired by his six-year-old son. "The first "Doublefaced" photograph was of my beloved son Bela," he said, "One day, he was sick and was sitting near me with a sad face. I asked him if I could draw a happy face on his sad face and he said 'okay,' so I did it. That was the first “Doublefaced” photograph, made in 2013."

So far this season, the theme of childhood has been all the rage: from Bottega Veneta's soundtrack of Peter and the Wolf to the Dolce & Gabbana runway that not only included embroidery of cats and stickmen, but children themselves. At Jacquemus, an enduring story of childhood continued, but with a distinct edge.

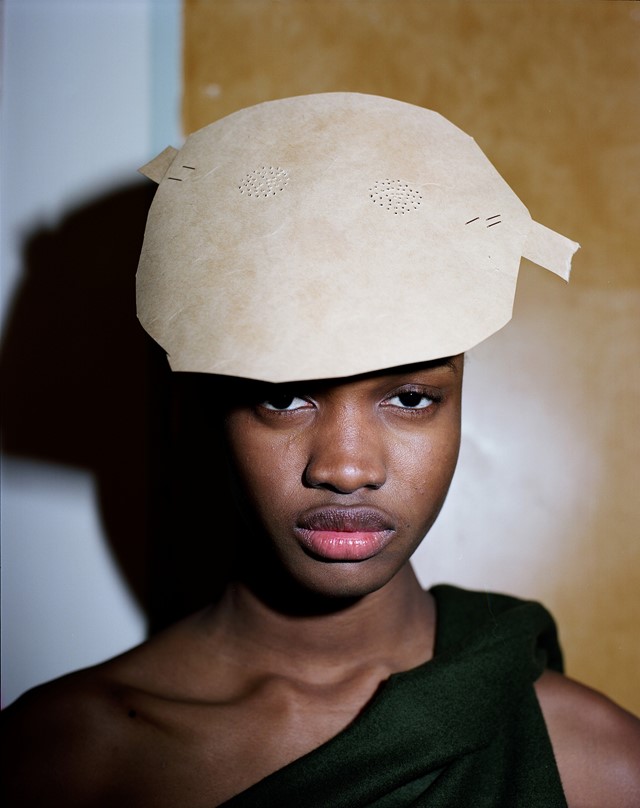

Invitations were decorated with pressed leaves, evocative of a kindergarten art project, occasionally a girl appeared on the runway with a childlike paper mask covering her face. Bare-chested models were not provocative but instead wore a kind of pre-Edenic naïveté. But rather than merely developing the themes for which he has become best known—a colourful, cheery playfulness—Jacquemus pushed A/W15 into primitivism.

The show space was raw, with girls walking amidst crumbling plaster and cables protruding from walls. The soundtrack was tribal, closing to the sounds of a child singing. Clothes were camouflaged, collaged and oversized; revealing breasts and long, barefooted legs. It was fresh, somehow wild, and ultimately powerful—kindergarten fashion at its finest, playful without the kitsch. What Jacquemus offered us was a dreamy, tribal fantasy of a world free from adult, capitalist fears and prejudice. And who doesn’t want to look at that?