After the premiere of the new Martin Margiela documentary, we recall his extraordinary all-white maison

In Paris’s quiet and principally residential 11th arrondissement is the home of fashion’s most mysterious players. The residents are justifiably proud of the 3,000 square foot space which they moved into a little over three years ago, which dates back to the 18th century. It has a suitably grand and – more importantly, given the label in question – evocative heritage. For nearly 100 years, this was a convent presided over by the Sisters of Charity, functioning primarily as an orphanage.

In 1939, one M Andre Peuble took over the building and founded the prestigious L’Ecole Professionnelle de Dessin Industriel. The vast majority of Paris’s industrial design luminaries from that period were alumni including the designer of the iconic Klein-blue Gitanes packet, complete with whirling Romany dancer and curling plumes of smoke.

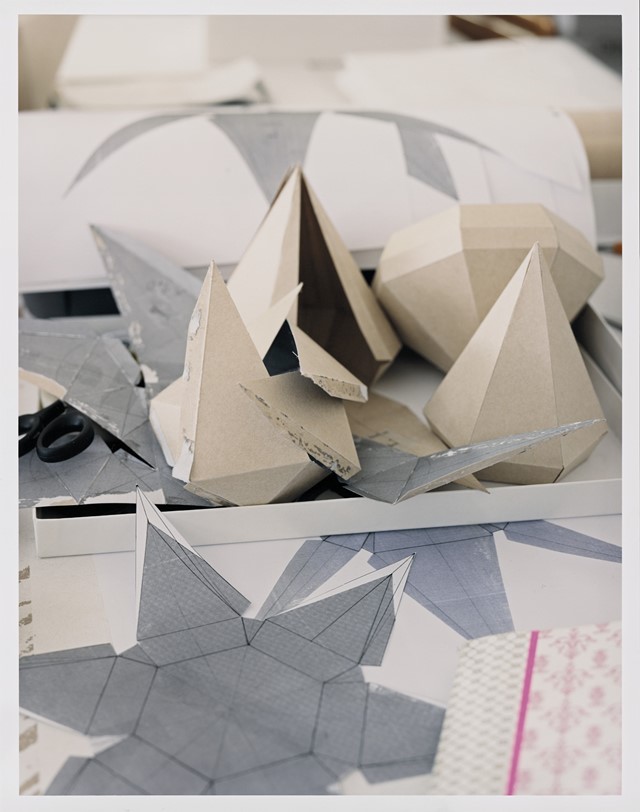

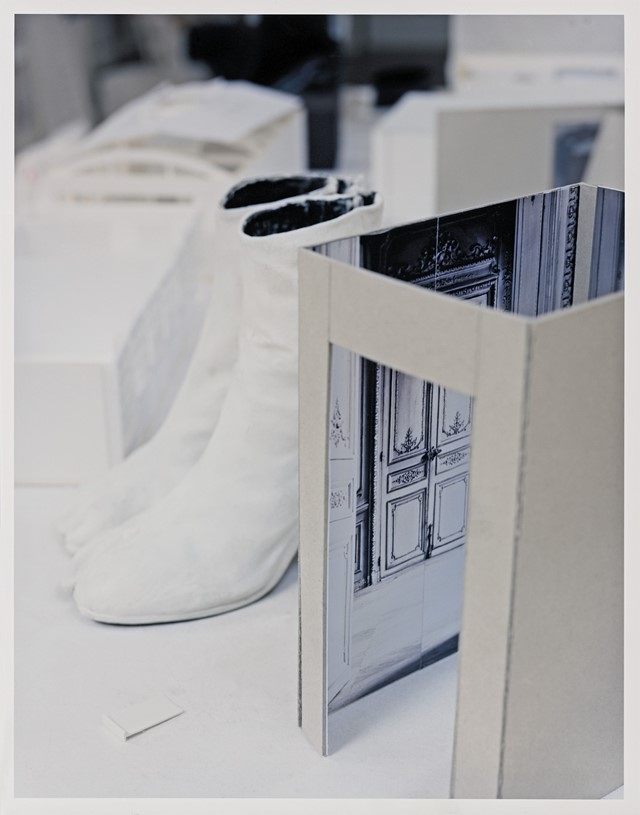

By the time Martin Margiela and his team arrived in December 2004, the place had been empty for a decade or more. The new occupants took up residence, however, only to find the classrooms had been left in just the same state as the day they were vacated – pens in inkwells, exam papers on desks and lessons still chalked on to blackboards, all covered in a thick layer of dust. Suffice to say, anyone who is familiar with the mindset of Martin Margiela might argue that, at 163 rue S Maure, the designer has found his spiritual home. After all, the effect of time passing on the world has been a career-long obsession of his.

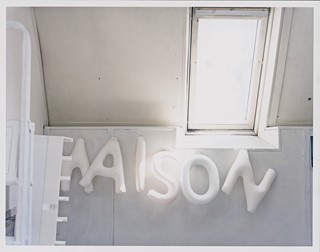

It took four months for the building to be prepared for its new purpose, and the powers that be at Maison Martin Margiela adopted just the same approach to the building’s restoration as they apply to everything else they touch. In particular, the use of white – or whites, in Margiela speak – was central.

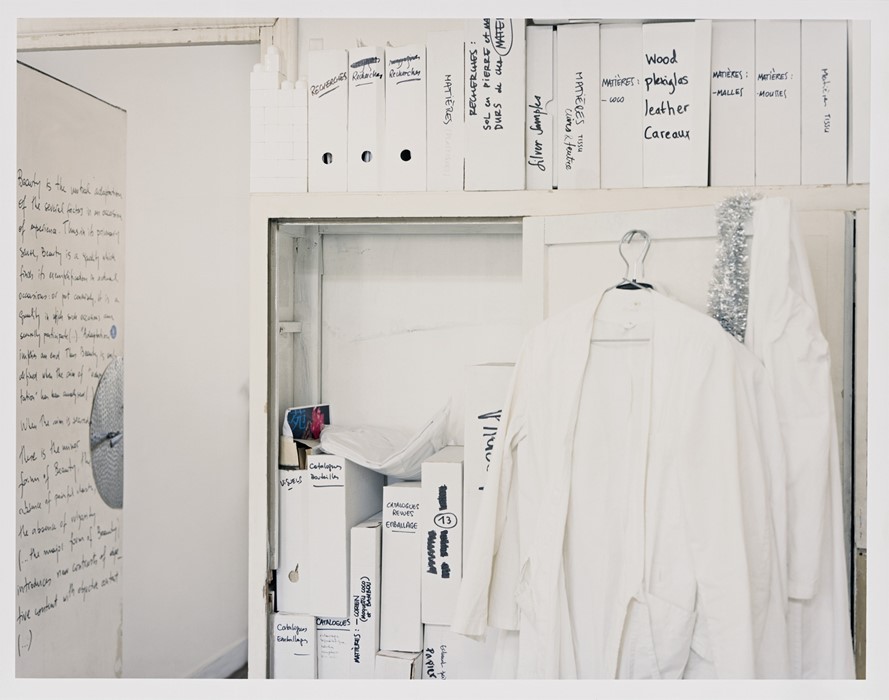

“There are two reasons for white – one practical, one conceptual,” says a spokesperson. It is the stuff of fashion legend that Margiela himself has never agreed to a face-to-face interview, or to his photograph appearing alongside any profile of his work. All statements that are issued by the house are careful to employ the pronoun “we” instead of “I”, thereby catapulting the concept of the superstar designer into oblivion. “When Jenny (Meirens, the label’s cofounder) and Martin started out they collected furniture from all over the place. They had no money and it was all in different styles, so to make it seem coherent it was all painted white.”

Of course, not just any old white will do. White emulsion is chosen to paint all surfaces for two reasons, both for its matt finish, and the fact that it is impossible to clean – any wear and tear caused by daily comings and goings are therefore left to tell their story for posterity. Paint is never applied to the whole space at the same time, so some of the rooms are almost yellow with age, while others are pristine in appearance – well, not quite.

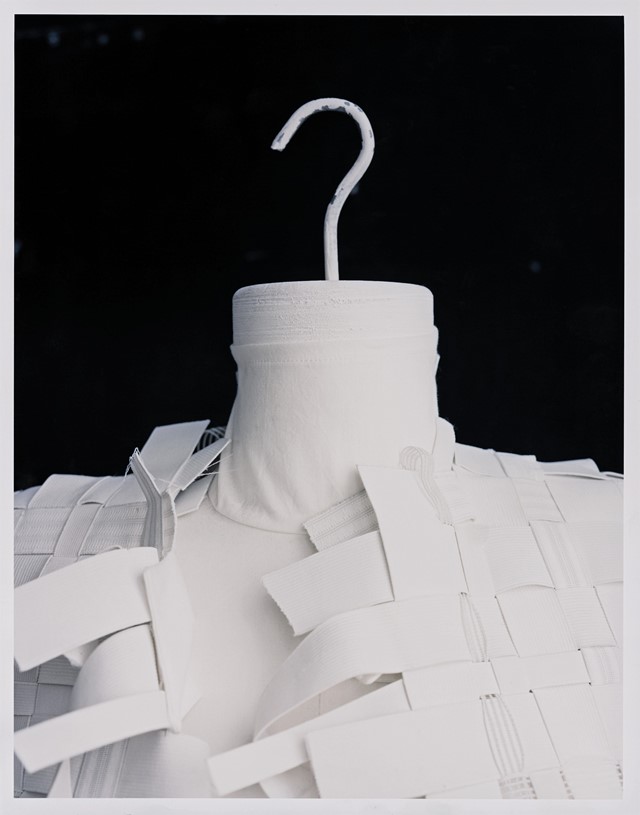

Although Margiela is not prone to analytical statements of his own, it’s safe to say that when he started out 20 years ago white – particularly uneven, scuffed white – was the antithesis of the mattblack aesthetic that dominated and was synonymous with the power-fuelled 1980s. In the same way the clothes he designed – garments principally reconstructed out of found pieces – were about as far from the strong-shouldered, virulently coloured, status-driven designs by the likes of Claude Montana, Thierry Mugler and even Jean Paul Gaultier that came before them.

Ah, Jean Paul Gaultier. Given Margiela’s reluctance to come forward, one can only hypothesise, but those close to the designer have, in the past, argued that his elusive public persona is a result of him having witnessed the merry havoc that the mainstream can wreak on a designer. Gaultier has long blamed the fact that he was overlooked for the top job at Dior when Gianfranco Ferré retired in the mid-90s because of his less than impenetrable image as the camp, kiltwearing presenter of Eurotrash.

Today, there is a full-time employee personally responsible for ensuring white remains central to the brand’s philosophy and aesthetic. This person orders the “blousons blanches” that all staff are requested to wear. The long version is the same as that worn by models in fittings, and the shorter coat is famously the uniform of the petites mains who execute the fine workmanship in the Paris haute couture ateliers. All the furniture, from the armchairs to chandeliers, is draped in white cloth, all notebooks are covered in the same material. “We are all responsible for painting our own desks though,” says our spokesperson, which seems fair enough.

In March 1998, Martin Margiela showed his first ready-to-wear collection for Hermès where he proved there was more to his lexicon than say, frayed ballgowns, skirts made out of old butchers’ aprons and cloven-toed “tabi” boots and shoes. The most perfectly proportioned tailoring, knitwear and deceptively simple – and beautiful – crepe evening gowns were a wonderful exercise in refined and very gentle understatement that has rarely been equalled, before or after. Margiela showed his signature collections and those for Hermès on his friends – women of all ages and professions – as opposed to models, only adding to the quiet dignity of it all.

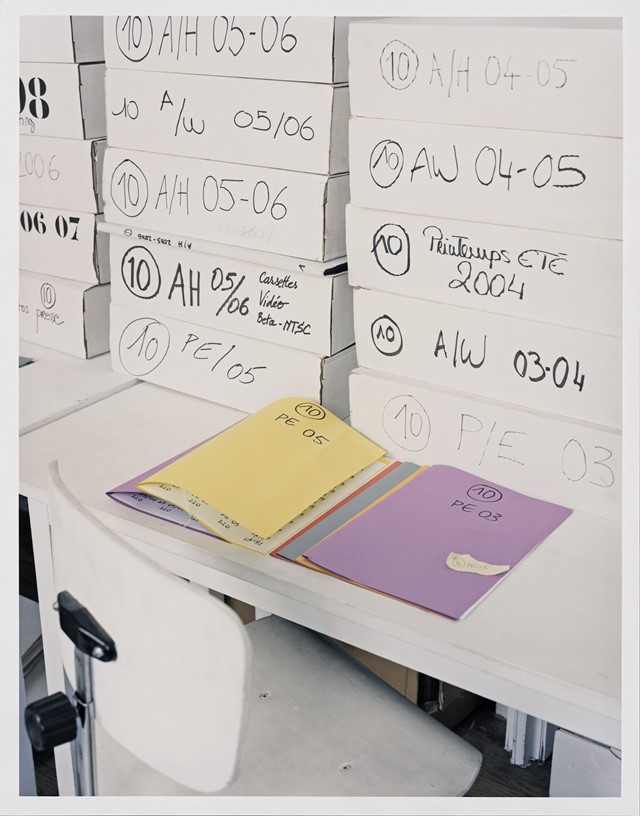

In 2002, Renzo Rosso, the owner and president of Diesel, bought a majority shareholding in the NEUF Group, the owner and operating company of Maison Martin Margiela. This facilitated worldwide expansion and enabled the designer’s aesthetic to reach a wider audience. Of course, this has changed things somewhat – there are now many more lines than there used to be, all numbered as opposed to anything as obvious as actually being named, and the reconstructed “artisanal” pieces are now strictly limited and shown during the biannual couture season.

Maison Martin Margiela’s love affair with white shows no sign of abating, although, “Silver is the new white, a bit,” apparently. The womenswear floor of the recently opened Hong Kong store is decorated in this metallic hue, inspired, it is believed, by nothing more haute than a glittering disco ball.

Watch The Artist is Absent, a short film on Martin Margiela by Alison Chernick, here. This piece is taken from AnOther Magazine A/W08 – explore the whole AnOther archive on Exact Editions now.