From Gareth Pugh to Christian Dior, we look at the fashion embracing the renaissance of runway theatricality

"I have repeatedly been inspired by the gestural quality of Mr Dior’s work" explained Raf Simons following his Christian Dior Haute Couture A/W15 show. With a stream of girls holding their cloaks and capes closed as they walked through the "Modernist, Pointillist church" constructed for the occasion in Musée Rodin’s garden, there was a quietly magical subversion of what has become the industry norm. No longer is the runway just model after model with deadpan expression, identical posturing, detached from reality. This subversion has been seen elsewhere as of late: the clasped hands of the girls at Gareth Pugh A/W15; when "girls met for a moment and gazed at one another" at Comme des Garçons; in the new Aganovich installation at Dover Street Market where articulated mannequin fingers appear to be summoning an otherworldly presence. During a period of industry shifts in marketing and show reviews, the stance of models is speaking to a new era of runway choreography and a renaissance of the dramatics that once marked the industry.

The Early Theatrics

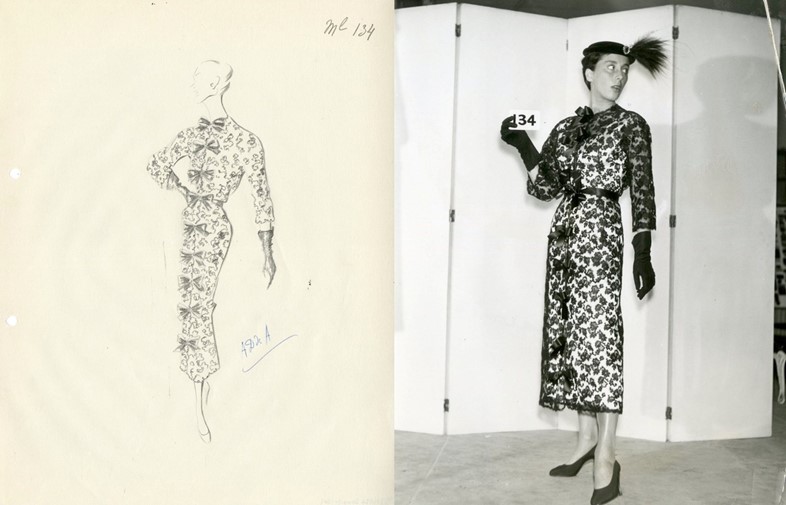

During the 1950s, the presentation of couture collections required models to hold a number on a card as they walked around the salon, enabling those in the audience to note down specific looks but resulting in slightly bizarre postures. As the decades continued and figures like John Galliano, Issey Miyake and Yohji Yamamoto made their way into the industry, this sense of performance and gesture developed to became an imperative part of a runway show: Galliano's first collection was inspired by a National Theatre production that he had worked on; Yamamoto was influenced by the stage costumes of Pina Bausch. As explained in Rizzoli's Yamamoto and Yohji, it was an era of "frivolity, sparkle, extravagance and flamboyance" where "the body took centre stage" and fashion became thoroughly, and brilliantly, theatrical.

The Impact of the Recession

With the arrival of Alexander McQueen in 1992, his devotion to performance became manifest in pieces that only became complete during the show itself (the spray-painted dress of S/S99) or frenetically choreographed routines of Deliverance (choreographed by Michael Clark in S/S04), and theatre on the runway reached a crescendo. Then, in 2008, just as the Lehman Brothers went into bankrupcy and the global recession hit, Phoebe Philo was appointed creative director at Céline. Budgets were cut; even those comparitively immunised against the economic crisis were keen to avoid an overt opulence and Philo championed an enviably streamlined aesthetic.

Her success – both visually and financially – was held as a beacon of modernity; as she said of her first collection for the house, "I just thought I'd clean it up. Make it strong and powerful – a kind of contemporary minimalism." Céline (and Philo) became synonymous with chic: a mature, understated elegance that subsequently became imitated throughout the industry. In fact, the recession actually didn't impact the luxury goods market. As Richemont's chairman Johann Rupert explained last month to CNBC, "People with money will not wish to show it. If your child's best friend's parents go unemployed, you don't want to buy a car or anything showy." But although brand presentations are dramatically pared-back by comparison to the era of Lee McQueen and John Galliano, there is a different kind of extravagance emerging; flying journalists all around the world in lavish staging of brand identity, and a return of the dramatics that once ruled.

The Quiet Renaissance

For A/W15 (and Christian Dior Haute Couture) there has been a renaissance of sorts, a shift away from the alienating, identikit runway demeanor towards a more unique expression of identity. At Max Mara A/W15, girls held their clothes around them in a posture evocative of, as Nicole Phelps described, being "nude under a towel that barely clings to her shoulders, or wrapped up in a chunky, hand-knit grandpa cardigan lying in the sand." There was an undone sexiness and a dishevelled reality about it all which made for something relatable and alive; these were girls captured in a moment rather than clotheshorses. Similarly at Maison Margiela, Galliano's girls offered a bewitching "new standard of beauty" (according to the accompanying show notes) – one that celebrated the individuality and patent performance of characters who hunched and flailed their way along the catwalk. Hands stuffed into pockets and gripping at fabrics, there was a slightly frantic attitude that, among a typically minimal Margiela scenography, showed a return to Galliano's heyday.

Gareth Pugh's grand return to London also embraced the theatrical. Opening with a Ruth Hogben video collaboration depicting an unnerving ritual in which the model cuts off her hair and daubs her face with a bloody cross, there was something equally ceremonial about the runway itself. Girls walked with an otherworldly serenity in their black, flowing robes, hands gently folded in front of them in the manner of a priest attending mass. There was a magic about it all; like Margiela, it was a moment of performance presented with a thorough consideration for the impact of presentation.

These elements continued to Dior, where earlier this month Raf Simons explained that his couture collection was inspired by the "innocent, gestural and personal" quality of Mr Dior's own work; as he told Jo-Ann Furniss, "the idea of drapery and gesture came from Flemish painting. It led to the cape coats with the concentration on one sleeve, an idea that is often seen in portraiture. At the same time the sleeve might be from Dior, with his gestures, his details.” Mr Dior's propensity to purposely break with perfection is something that the collection deeply engaged with, presenting extravagant couture pieces within the context of humanity. And perhaps that is what these designers are striving for: offering an opportunity to embrace the illusion of reality through a thoroughly-orchestrated performance, simultaneously dramatising and humanising their collections. It is what the theatre gives us, it is what McQueen did best – creating pieces for women, but distinctly fantastical ones – and it is something that the industry has sorely been missing.