AnOther applauds the groundbreaking writer whose wealth bought her sexual and sartorial freedom

In what is a perfect example of the double standards rife during the post-Victorian era, a prudish establishment banned pretty much any graphic depiction of sex in art and literature, but the academic classes were obsessed by it. Sexologists explored the nuances of sexual identity and gender, proposing theories by which to understand those that fell outside of the very narrow parameters of ‘normal’. Meanwhile, art and literature exploring the subjective experiences of these people was very often censored. One such example of this was the 1928 novel, The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall.

Despite opening with a clause from the author stating that all the characters in the book are “purely imaginary", Hall’s seminal work contains many parallels to her own experiences. Featuring a young girl named Stephen Gordon, the book traces the development of this central character from confused child, turbulent adolescent, to independent woman in a lesbian relationship. The book, wrote Esther Saxey, was a “work of propaganda; it tried one strategy after another to enlist the reader sympathy for Stephen, and for the ‘miserable army’ of men and women like her. Because of this agenda it was banned for obscenity within four months of its publication."

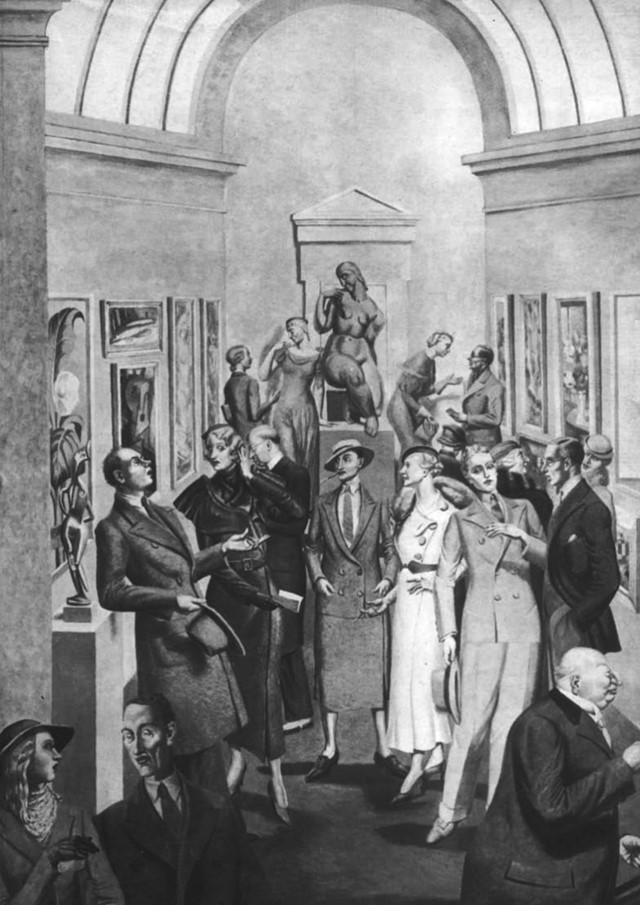

As a lesbian, Hall enjoyed a long-term relationship with British sculptor Una Troubridge, who she lived with until her death. The pair are depicted in Gladys Hynes’s 1937 painting Private View, in which the couple are gendered as masculine and feminine, with Trowbdige’s glamorous dress, high heels and feminine pose, slinking towards Hall, directly contrasting Hall’s masculine skirt suit. The picture itself is loaded with depictions of masculinity and femininity; Hall is positioned directly below a classic nude female sculpture, and beside the couple is an ambiguous character, which could be a beautiful woman in a trouser suit or, more likely given they are wearing trousers, a man with delicate features.

Feeling 'wrong'

In The Well of Loneliness, young Stephen is conscious of feeling “all wrong” — “If she dressed like a woman she looked like a man, and if she dressed like a man she looked like a woman,” wrote Hall. Through dressing up, Stephen began to notice how different clothing made her feel. While make-believing dressed up as Nelson, she says, “Yes, of course I’m a boy. I’m young Nelson, and I’m saying: 'What is Fear'”. And with this realisation begins the fight between how our protagonist feels comfortable and what is expected of her. “How she hated the soft dresses and sashes, and ribbons, and small coral beads, and openwork stockings! Her legs felt so free and comfortable in breeches; she adored pockets too, and these were forbidden – at least really adequate pockets,” writes Hall in The Well of Loneliness.

Finding independence

Independence for Stephen in The Well of Loneliness came following the death of her father, rendering her independently wealthy. “Stephen now dressed in tailor-made clothes to which Anna (Stephen’s mother) had perforce to withdraw her opposition,” writes Hall. Despite the preamble to The Well of Loneliness stating that the novel was fiction, this particular plotline almost directly mirrors Hall’s own life as she, too, became independently wealthy at the age of twenty-one after inheriting a substantial private income. In a 1990 article about the dress of Radclyffe Hall and her partner Una Troubridge for Feminist Review, Katrina Rolley wrote: “This income allowed her to live independently from her family and to discard the 'feminine' clothes chosen by her mother in favour of tailor-made styles. Radclyffe Hall's wealth and independence later allowed her and Una Troubridge to disregard public opinion and appear together in clothes which announced, to an informed viewer, their respective roles within a lesbian relationship."

Class privilege

Wealth didn’t only buy Hall the masculine clothes she craved as a youngster but, combined with her standing in the upper echelons of society, it enabled her much more freedom to behave the way she pleased than she would have if she had been a few rungs down the class ladder. Hall’s masculine dress and eschewing of traditional female roles in order to live with Troubidge very often came off as eccentricity. “Whilst the couple's wealth and class freed them from the constraints of public opinion, it also meant that for viewers who were unaware of their sexuality, especially those distanced by class, their appearance might be (mis)read as part of the aristocratic tradition of eccentricity, especially since Radclyffe Hall was also a writer,” wrote Rolley. “Even Patience Ross, who worked for Radclyffe Hall's literary agent during the publication of The Well of Loneliness, still believed the couple to be "platonic friends who had a mission to help 'those poor people.'”