We celebrate the iconic collection that subverted shoulder pads and parodied patriarchal silhouettes

A common thread that runs throughout the avant-garde fashion design of the 1990s is a thorough critique of the visual language of the 1980s: a thorough dismissal of the golden era of sculpted bodies and hyper-glossy aspiration. Rei Kawakubo is a designer who unmistakably helped pioneer this renegade aesthetic, a woman whose creations have never accepted the body as a limitation and who tackled the cultural tropes of female body image and its connection to clothing in her Spring/Summer 1997 collection, titled "Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body" – widely remembered as the "lumps and bumps" collection.

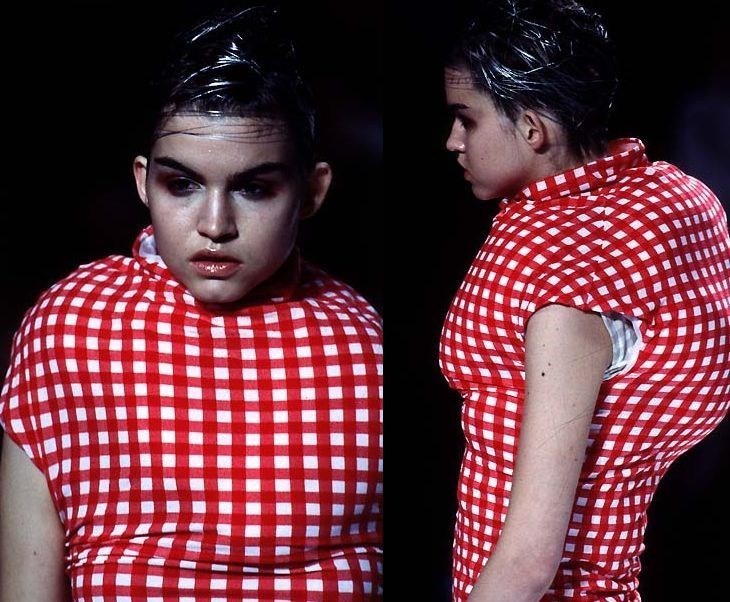

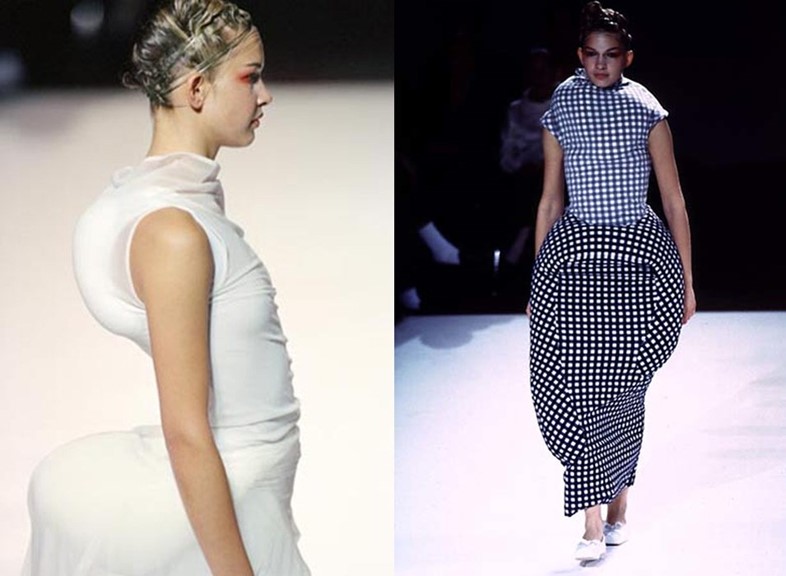

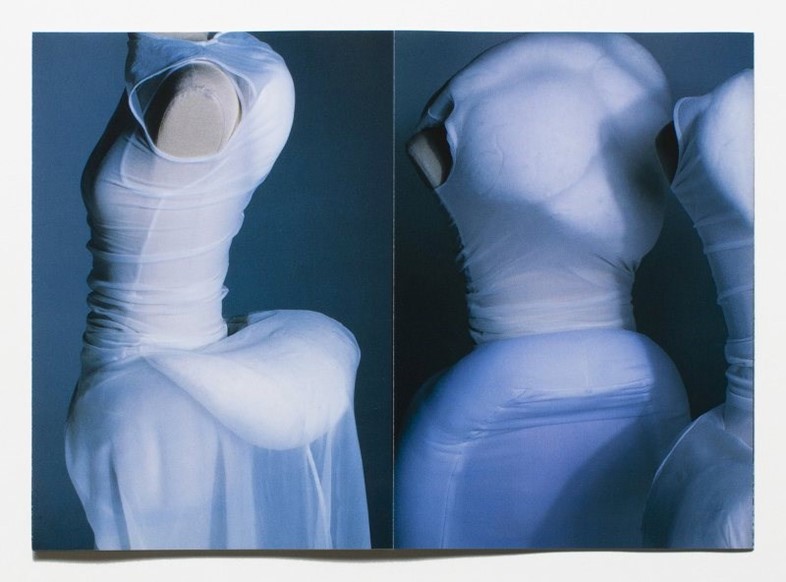

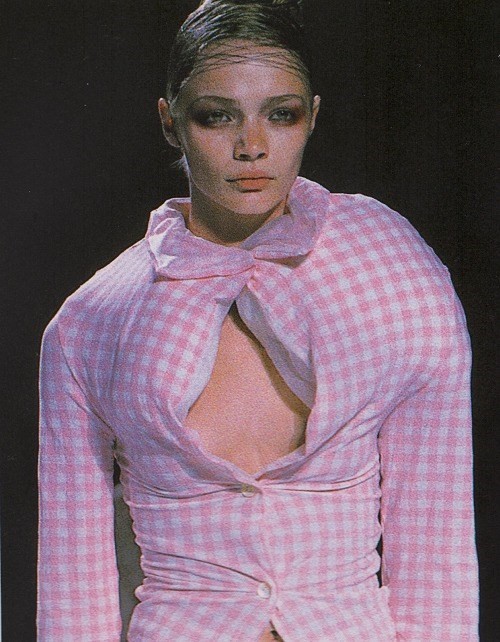

Just days before Kawakubo showed her collection, in Milan Tom Ford was polishing his dark, glossy brand of louche and sweaty sexuality at Gucci in a show that starred Amazonian supermodels wearing nothing but a logo-embellished thong and an intense amber glow. Kawakubo, however, chose to parody these beauty ideals and create entirely unfamiliar silhouettes, constructing garments lined with kidney-shaped down pillows sewn into slip linings. The resulting pieces presented a mixture of visual themes, ranging from an ironic commentary on expectations of women and cleavage-enhancing bras, to a reimagining of the maternal figure and exaggeration of the protruding curves of the female anatomy. Here, the body was distorted and shaped by the clothes themselves, rather than the clothes being enslaved to the body.

The Show

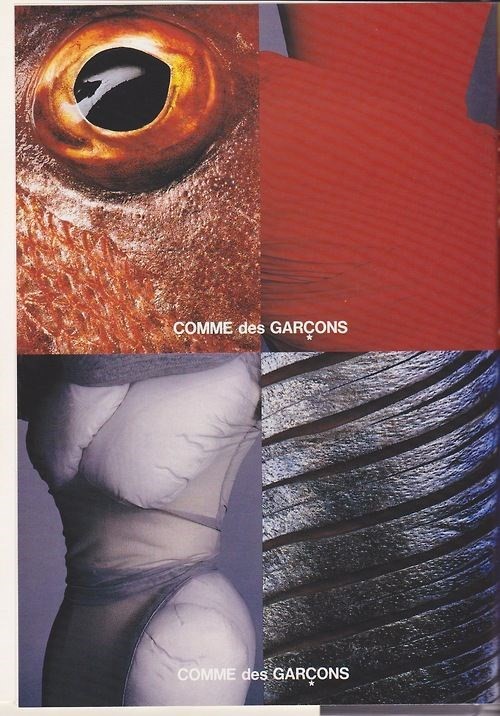

“After extensive searching and thinking out for new ideas, just before time ran out, I realised that the clothes could be the body and the body could be the clothes,” said Kawakubo of the collection in UNLIMITED: COMME des GARÇONS. “This was an idea for possible new clothes. I then started to design the body. I didn’t expect them to be easy garments to be worn everyday, but Comme des Garçons clothes should always be the new to the world and inspiring. It is more important, I think, to translate thought into action rather than to worry about if one’s clothes are worn in the end. This is probably why the collection stimulated strong feelings in many people.”

“The clothes could be the body and the body could be the clothes” – Rei Kawakubo

One of the most striking things about Kawakubo’s collection is that it makes use of padding – but subverts its conventional application. Considering that in the 1980s, when padding was used as a way to broaden shoulders to powerful effect and achieve a desired body shape, Kawakubo’s work is distinguished by a decidedly sparse and subtle use of it. Here, in 1997, it becomes the centrepiece of the collection, pulsating through the garments at the shoulders, hips, belly and back. The choice of pale pink and baby blue gingham checks hint at domesticity, while the stretch nylon fabric seen throughout the collection allows the fabric to follow the Punchinello proportions of the silhouette.

“I remember feeling rather uncomfortable about the 'lumps and bumps' collection,” recalled Suzy Menkes of the show, which was held at Musée national des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie. “At first look, it seemed like a disfigurement – as though these were cancerous cells protruding through the fabrics, which appeared, by contrast, as upbeat; even jolly. As so often with Rei Kawakubo's collections, there was the shock of incomprehension followed by visual memories that last a lifetime.”

The People

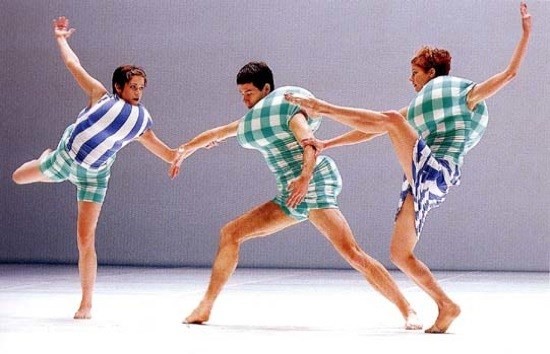

The collection resulted in one of the most seamless collaborations across creative disciplines. Merce Cunningham, the New York-based choreographer famed for pronouncing the independence of dance from music, was instantly drawn to the way the clothes affect movement. Often a collaborator with other artists, Cunningham prominently worked with Robert Rauschenberg, who once costumed Cunningham in solid black accessorised only by a chair attached to his body. For a 1958 performance, Cunningham asked Rauschenberg to make him a sweater with four arms, an item that coincidentally Kawakubo designed 25 years later.

“I like the way the shapes of the costumes change on the bodies”– Merce Cunningham

“I like the way the shapes of the costumes change on the bodies,” Cunningham said of the CDG collection in 1997. "If you saw the person from the front, you expect a certain familiar image. But when a person turns around, you see a totally different image, which is quite unexpected from the shape of the costume. And that was such a delight to my eyes.” The collaborative performance, titled Scenario, premiered in October 1997 at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, where the dancers’ movements took place against an all-white stage, lit with fluorescent lighting to the column of repetitive sounds made by Takehisa Kosugi, the company’s musical director. Far from perpetuating the stereotype of the perfect body, Kawakubo’s costumes challenged the vanity of the dancer and the gaze of the spectator. Prior to the performance, Kawakubo said that the costumed “will be emphasized and exaggerated by the movement of the dancers. The fact that Merce has always placed the most importance on chance is something I empathise with.”

“It is like viewing certain Francis Bacon paintings: a magnifying glass seems to draw your eyes to the points of tension where the encounter takes place at some unspecified moment between artists and model, choreographer and dancer, dancer’s costume and your eyes and ears,” wrote France Grande in 1998. “In an array of different costumes, some with humps, some in Lycra, the checks and dislocated stripes magnify the tension between torso and legs, between one body and its partner. Then suddenly dancers appear, all in the deepest black. Then in a dazzling red that draws them together, marking the return of the corps de ballet.”

The Impact

“The Spring/Summer 1997 collection of Comme des Garçons set out to explore and question assumptions of female beauty and notions of what is sexually alluring and what is grotesque within the Western vocabulary,” writes Francesca Granata in her upcoming book Experimental Fashion: Performance Art, Carnival and the Grotesque Body. “Her collection manifests the relation between the pregnant body, the female body and the disabled body – three types of bodies that deviate from the norm – a construct, which as showed by a number of theorists, is deeply gendered and raced.”

“Her collection manifests the relation between the pregnant body” – Francesca Granata

According to Granata, this exploration was, however, not always well received or easily digested by the fashion establishment. While some of the press praised Kawakubo’s collection (particularly the art press, style magazines and newspaper-based journalists), the collection was not unconditionally embraced by the fashion glossies: “Both Vogue and Elle made an indirect critique to the Japanese designer’s work by photographing the collection with the pads removed.”

Despite the lack of editorial success, the collection itself became a collectible piece of design history for many people, some of whom wore the garments with the down padding removed. “Wearing it I felt like an animal in oestrus: very fleshy and sexy and powerful,” says Kelli Donn Crosby, a sculptor and performance artist who modelled the collection in i-D magazine. Just last month, London-based Kerry Taylor Auctions sold a full look from the collection, pillows and all, for £22,000. Today the collection stands testament to a fearsome statement made by a spectacularly modern designer. Never more so than now, in an image-heavy world of cartoonish body and health culture and virtual supermodels, could this study of the female body, and the way we see it, be more pertinent.