Back in September 2013, Rei Kawakubo reinvented the traditional approach to runway collections. Presenting her S/S14 offering, comprised of only 23 outfits – each a sculptural exploration of form and fabrication, rather than a traditional ready-to-wear garment – she was entirely dismissing familiar fashion formulas (X amount of looks, Y amount of accessories, etc.) to create one of her own: one that rejected conformity in favour of creativity. To the industry's delight, she has continued to present these exceptional collections (from which the readier-to-wear pieces draw inspiration), offering a relieving alternative to the consumable frenzy currently infiltrating the industry. This is fashion for fashion's sake, fashion which revels in emotional provocation, and fashion which, as Jo-Ann Furniss wrote in 2013, means that “to pass judgements on ‘wearability’ or ‘practicality’ just seems facile." However, there are those who buy – and wear – these pieces; those for whom restriction of physical movement is merely an aesthetic necessity, who not only keep their prized garments locked away in an archive but use them to enlighten their day-to-day life. They are, brilliantly, the people who power an industry built on retail – and one of those women is Michelle Elie.

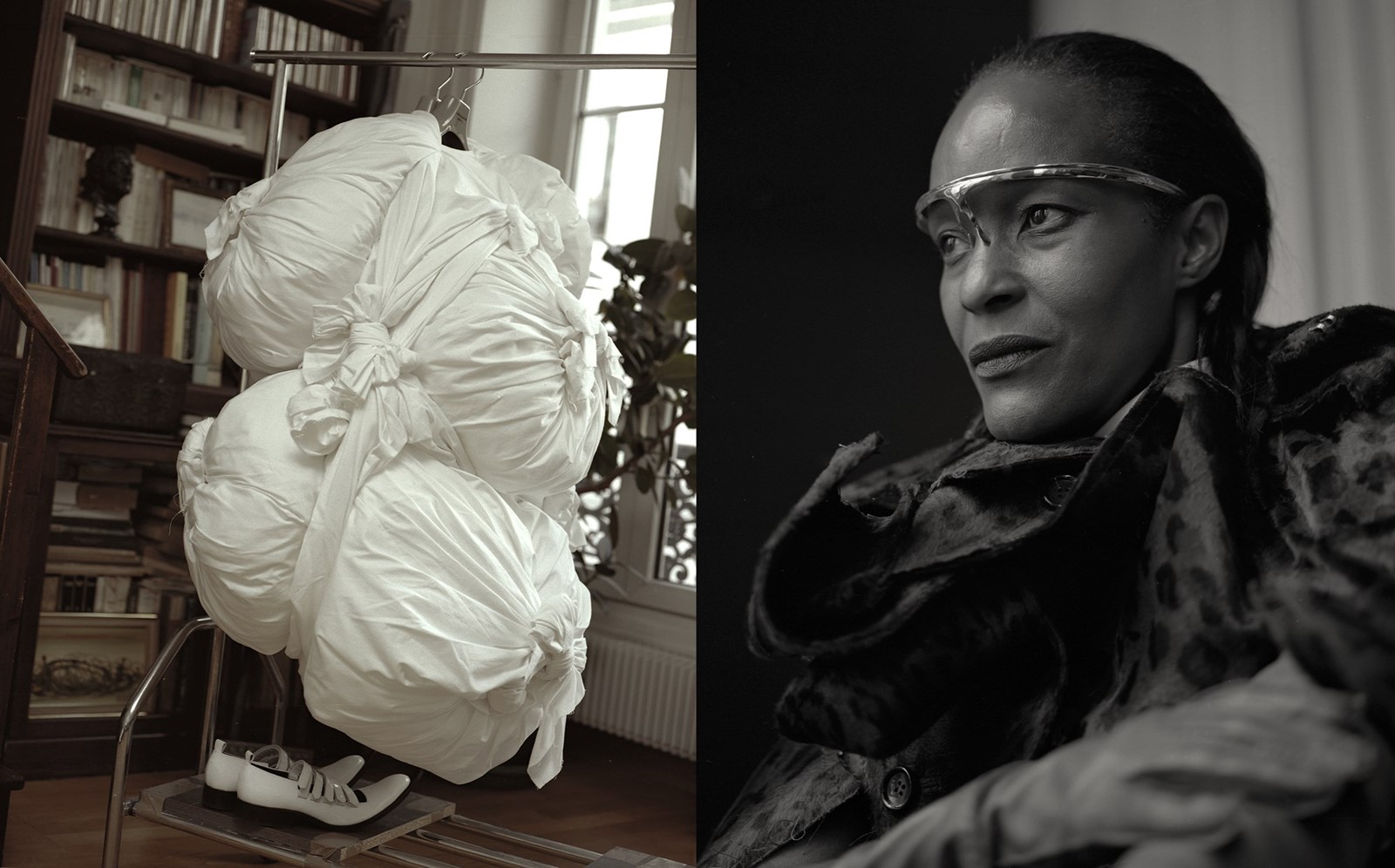

Michelle Elie bought her first CdG piece back in 1998: a dress from the iconic "Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body" collection. It was a collection that riffed on the female form; as Francesca Granata writes, it managed to manifest "the relation between the pregnant body, the female body and the disabled body – three types of bodies that deviate from the norm." "I didn’t expect them to be easy garments to be worn everyday," wrote Kawakubo in Comme des Garçons: Unlimited – but so enamoured was Elie by the "form of the tumour" dress (she describes it as her Comme "turning point"), that she subsequently wore it to pose for a pregnancy portrait when carrying her son (Zec, now 16, and the recipient of the Roger Ballen-printed leather jacket captured in these pictures). A collection that hunched backs and distorted abdomens in a Bakhtinian subversion of female physical boundaries thus became Elie's pre-natal wear: possibly the greatest context imaginable, surpassing even Kawakubo's own expectations. But Elie's love of Comme "has nothing to do with the shape," she says, "and nothing to do with the weirdness. It has to do with something unspoken about these pieces, something that generates a poetry which, whether you like it or not, you cannot stop looking at."

Wardrobe aside, Elie herself is someone you can't stop looking at: born in Haiti, raised in New York and now situated in Cologne, she is physically arresting and speaks with an accent that is heavy yet indistinguishable. She has her own accessories line – Prim – which she is remarkably reserved about (it is rare, and refreshing, that one's own label wouldn't be front-and-centre in a conversation with a fashion magazine about fashion), and she is a mother of three (the aforementioned owner of the Comme/Ballen jacket, and two younger). She plans to put them through college, so – much to her dismay – is cutting back on her collection as the Comme prices increase in line with their physical extravagance. Since she started attending international fashion weeks a few years ago, she's also become a familiar face on street style blogs (of course she is, she wears full-look Comme), but is remarkably unabashed by it all; recognition is clearly not her motivation in purchasing these clothes. In fact, when she was seated front row at Comme's A/W16 show, she seems to have been more embarrassed than anything, explaining that "I usually prefer to stand next to the photographer because you get the best view. Then, they put me next to Carine Roitfeld! First of all, I don't deserve that seat. Second of all, I'm happy standing. There are so many editors that are working their ass off to do this. I'm just wearing it!"

But perhaps that is as valid a reason as any: it’s certainly the customers who pick up the front row tickets at couture shows, and one must recognise that Elie's dedication to Comme is quite impressive. Firstly, she has to drive her collection around with her if she plans to wear it (they are too heavy and dimensional to pack, and often too slow and expensive to ship; secondly, it is a gargantuan investment – a piece can reach five figures. She now buys a piece a season, sometimes an extra in the sale, explaining that the interaction is always a bit of a struggle, whether that's physical (literally; apparently you often can't try these pieces on before you purchase them), or financial. "It means that, when I get it, I really, really appreciate it – and it's this constant challenge which I think is also interesting, because it makes you rethink a piece, think about why you are fascinated by it." She mourns for pieces she hasn't bought, those which have something magical about them to her, which "give her a certain energy, a certain inspiration," which speak to her in a certain way. It's a feeling that she explains some people might get from their family, or from music. She gets it from Rei.

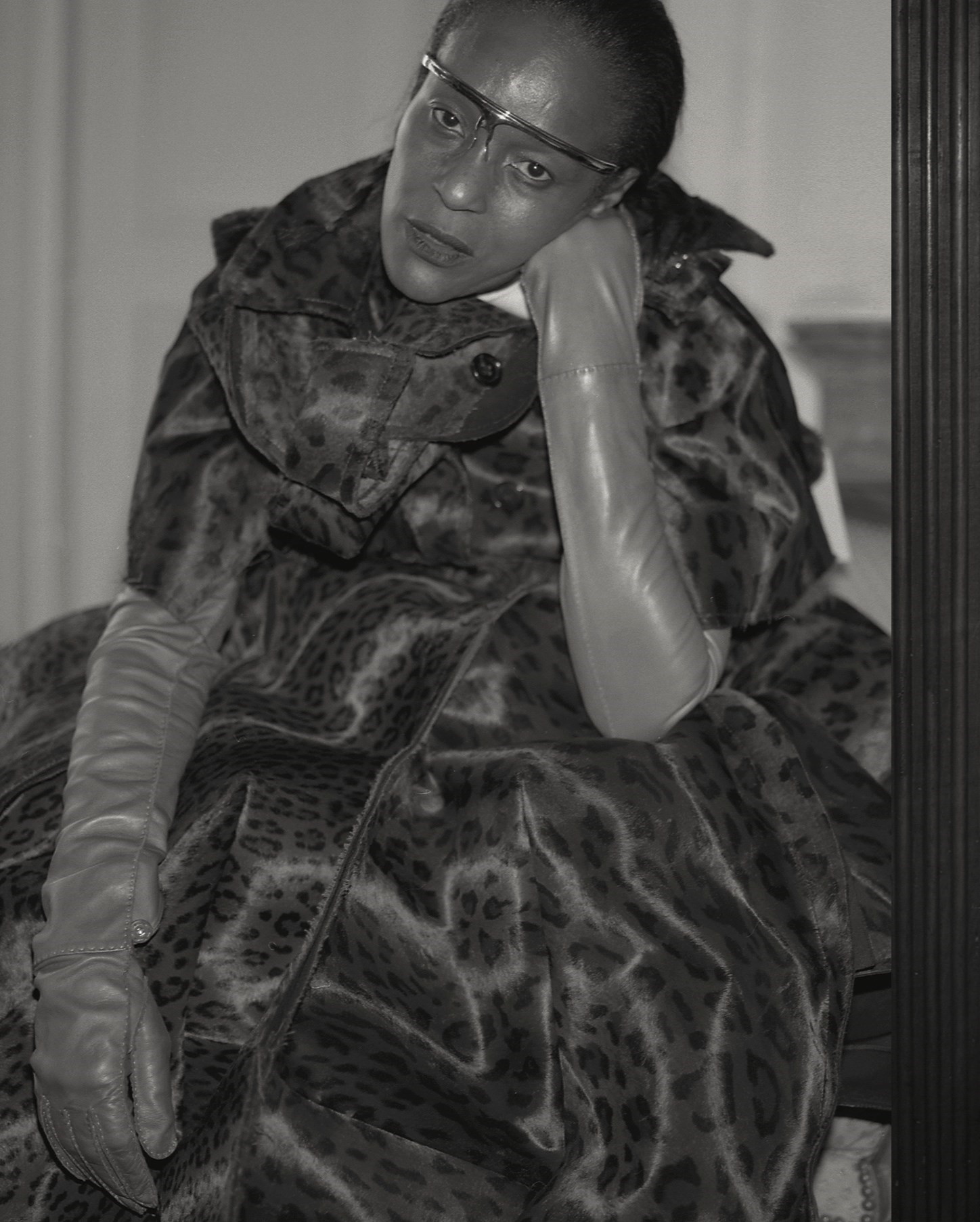

However, Elie's devotion to creating her own, extraordinary aesthetic is not exclusively focused on Kawakubo's designs. At the start of our conversation, she reels off a quick-fire monologue of her favourites throughout history (they include Nicolas Ghesquière at Balenciaga, Raf Simons at Dior, Undercover, Mugler and Margiela), and it is passionately encyclopaedic. Here, she wears Paco Rabanne face jewellery by Julien Dossena – "I saw the show and was like, that's fresh, that's modern," she recalls. "I tried to get it through every means possible – but they don't produce them. They send these things down the runway, but in real life you get a watered-down version." She didn’t want the palatable equivalent, so managed to get in touch through a friend of a friend and, voilà. It happened; you get the feeling that Elie makes things happen.

It's funny talking to Elie – as someone who is well acquainted with these collections, you realise how easy it is to forget that someone might actually pop into a store and buy one of these pieces. It gives a new perspective on it all – one that Elie manages to summate thus: "I'm interested in the customer who is buying the clothes and wearing them, without the hair, without the make-up or the entourage. They're giving it the importance; they're the ones who go and buy it, and then is the impact, the philosophy as strong off the runway or out of the pages of a magazine? Does it have the same strength as it should have?” Seeing Elie decked out in the fifth look of the Blue Witches collection, which Adrian Joffe explained was about “powerful women who are misunderstood, but do good in the world,” it seems that the answer is a resounding yes. She's translated it into her own universe, and appears a powerful woman indeed: what greater celebration of Comme, and fashion, is there than that?