In a season rife with badge-style accoutrements, we examine the political signification of the beloved accessory

It may seem difficult to judge the cultural resonance that wearing badges has had in recent history, or why people create, collect and champion the badges they do. From birthdays to Blue Peter, the accessory is used to commemorate heroes, symbolise political party allegiances and can even be a means of rebellion – but this season, fashion runways from Alexander McQueen to Miu Miu employed badge-style embellishments to proclaim their own messages. Here, we explore the evolution of badge wearing, and what it means to different spheres engaging with the visual tradition of rebellion.

The Historical Object

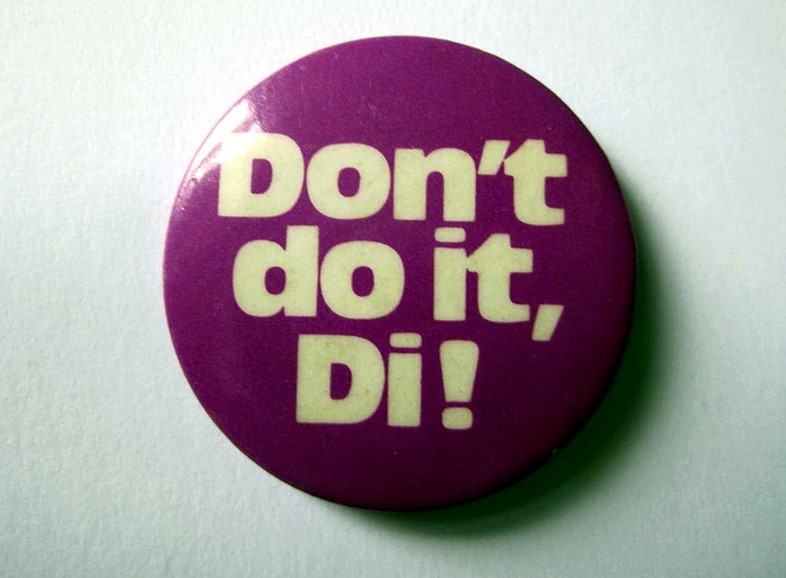

One could trace the narrative of British history from the badges that we have created across the decades; for every cultural or political upheaval, there has seemingly been a badge to accompany it. In 2004, the subject was curated into an exhibition held at the British Museum that aimed to explore the badge as a symbol of the wearer’s identity and beliefs. Displaying everything from the badges that decorated the suffragette movement to those declaring John Prescott a ‘Sex God,’ it was one of the very few comprehensive considerations of British badge wearing since the start of the 20th century, documenting "a century of stroppiness," wrote The Guardian. Arguably, they explained, one of the most subversive badges on display was one of the smallest, with the words, ‘Marbles Reunited,’ covering its tiny surface. This badge called for the British Museum’s Parthenon marbles to be returned to their home in Athens – an issue that continued to rage until 2015, when Greece ended the legal battle and left their beloved marble in Britain. The badge was displayed metres away from the disputed carving, in a bold move by curator Amanda Gregory: it was a micro-sized mutiny against the museum, symbolic of the purpose of badges in general. The exhibition was one the of largest dedicated to revealing our enduring love affair with the attachable accessory, our reverence of its ability to visually affiliate a person with wider movements.

The Political Statement

Beyond the Parthenon marbles, pin badges and fabric patches are often laden with subcultural connotations; ever since punks customised their leather jackets with anti-Thatcher slogans, they have been firmly established as part of an aesthetic of rebellion. Vivienne Westwood hails from this era and, while her early years might have been more DIY than her modern runways, her recent collections still reference this past. Her S/S16 collection featured badges proclaiming her support for the Scottish referendum (she took her closing bow proudly and prominently displaying her own badge), and S/S16 saw models including Alice Dellal pinned with plastic spheres proclaiming Climate Revolution. Politically charged fashion is what Westwood has made her name creating – but she is certainly not the only fashion-conscious advocate of the badge's power.

Reba Maybury, founder of Wet Satin Press, is another politically-charged badge wearer: “There’s something about me that likes being quite confrontational. Wearing a badge that says ‘Tory Slave’ or ‘Bollocks to Austerity, Tax the Rich’ is just my way of dealing with the current political climate," she explains. These badges are only a fraction of Maybury's collection, whose other current favourites are the efforts of Central Saint Martin’s graduates Luke Brookes and James Buck, the masterminds behind Badgetaste. “I think what James and Luke are doing is completely original,” she tells me, pointing to her badge encasing a sagging condom, while others from their offering are pressed with yellowing cigarette ends and pubic hair. “It's kind of throwing people a little bit, because it’s kind of disgusting but I think that’s fantastic: it's anti-fashion.” While a plaster framed in plastic may not be everyone’s idea of the perfect accessory, it certainly challenges the status quo about accepted codes of dress.

For Buck, experimentation with badges began during his time at Central Saint Martins: “Initially, I saw the badge using pubic hair as a pop art take on mourning jewelry. Putting something personal into an industrial machine felt nicely perverse.” There is an authenticity in these special objects; from their conception the process is rooted in their subversive ethos to remain playful, yet thoughtful. When confronted about high fashion’s take on a typically DIY process, Brooke responds, “I do wonder if buying and wearing something which looks like one you could have made yourself is extra luxurious in a world where you can instantly tell when something has been produced by an industrial juggernaut.”

The Fashion Statement

DIY is not the only sphere of fashion embracing the badge. For A/W16, Sarah Burton covered garments in bejewelled badges including crescent moons and witches toadstools at Alexander McQueen, creating an assortment of talisman-like trinkets. Ashley Williams had rebellious school girls pinned with ‘Prefect’ badges; Sam McCoach at Le Kilt created safety pin badges with scraps of tartan, hailing to her Scottish heritage with a nod to punk culture. At Sacai, some outfits were made entirely of military style patches and crests, with the odd Sacai modification and the introduction of, ‘love will,’ and ‘save the day,’ badges (a reference to a 1987 Whitney Houston song) interrupting the military regalia. If the military badge aims to identify the heroes amongst us, then the badges at Sacai must have been creating clothes fit for superwomen, empowered by a single Whitney Houston life mantra.

In true Miuccia Prada style, the patches at Miu Miu were a little harder to interpret. In a collection that combined cultural and historical references to create denim tailcoats paired with pink fluffy slippers, Miu Miu also adorned garments with 1950s-inspired American name patches accompanied by a few flowers, deer and flamingo. The names on these patches evoked those of stars from Hollywood’s golden age: the likes of Gene (Kelly), John (Wayne), but with their placement and figuration emblematic of workwear. "Nobility and misery," said Mrs Prada backstage – and her uniting glamour and working class reality seemed just that, simultaneously reflecting the growing disparity between fashion and the real world, but also how working class culture has become an endless source of inspiration for designers. It seems that perhaps the badge itself is the perfect emblem to reflect this dissonance between nobility and misery: seeing a medium most affiliated with subversion and protest on a designer runway is a subversion in itself. As ever, Mrs Prada is consolidating a history of visual cues within a solitary garment; a garment which will, surely, take on further meaning once actually worn by Miu Miu acolytes come autumn.