“Odour, oftener than any other sense impression, delivers a memory to consciousness little impaired by lapse of time, stripped of irrelevancies of the moment or of the intervening years, apparently alive and all but convincing,” wrote Roy Bedichek in The Sense of Smell (1960). “Not vision, not hearing, touch, nor even taste – so nearly akin to smell – none other, only the nose calls up from the vasty deep with such verity those sham, cinematic materialisations we call memories.”

It is memory that informs our taste for scent, and what links the notes of a fragrance to the inescapable and often subconscious feelings of nostalgia, joy, repulsion and sex. Seemingly far away experiences such as childhood holidays, first kisses, parental influences, early diet and geographical upbringing contribute to our sense of smell, which is undoubtedly the most neglected of all our senses. Think about it: we seek beauty in visual art and nature, decorating our homes to please our eyes; we search for new music and shift through crowds to get closer to the stage; we spend time and money on sampling fine cuisine, perhaps even learning to cook it ourselves; and we indulge in soft cashmere sweaters, crisp shirting and silk sheets to feel against our skin. Yet, often our noses are subject to a bottle of perfume that we’ve worn for years, unwavering in its nuance and individuality, and the variables such as seasons, weather, and our moods are hardly considered.

“I was that consumerist Londoner that could afford to buy whatever perfume I wanted on a whim,” says Jessica Hannan, who moved to Berlin four years ago to join the city’s distinctively less label-clad creative class. Hannan left her job as an editor at Net-a-Porter for a flat in Neukölln, a colourful corner of the city that has been permeated by Turkish culture as a result of immigration. “I found these amazing Turkish perfume shops where they had all of these single-scent oils that people would buy and mix it themselves – it’s incredibly different to the way we understand perfume as Westerners.” After gathering a selection of oils, often by drawing the pictures of flowers for the elderly men behind the counter, followed by training at perfumery Frau Tonis, Hannan began to make bespoke perfumes for herself and friends. “My friends describe me as a hipster Mystic Meg,” she says, before recalling the time she stockpiled the soon-to-be discontinued BodyPeach in the Cardiff branch of Body Shop as a child.

“You can read as many books as you like, but it’s through sitting with somebody and understanding how to build scent with them that makes it an emotional exchange” – Jessica Hannan

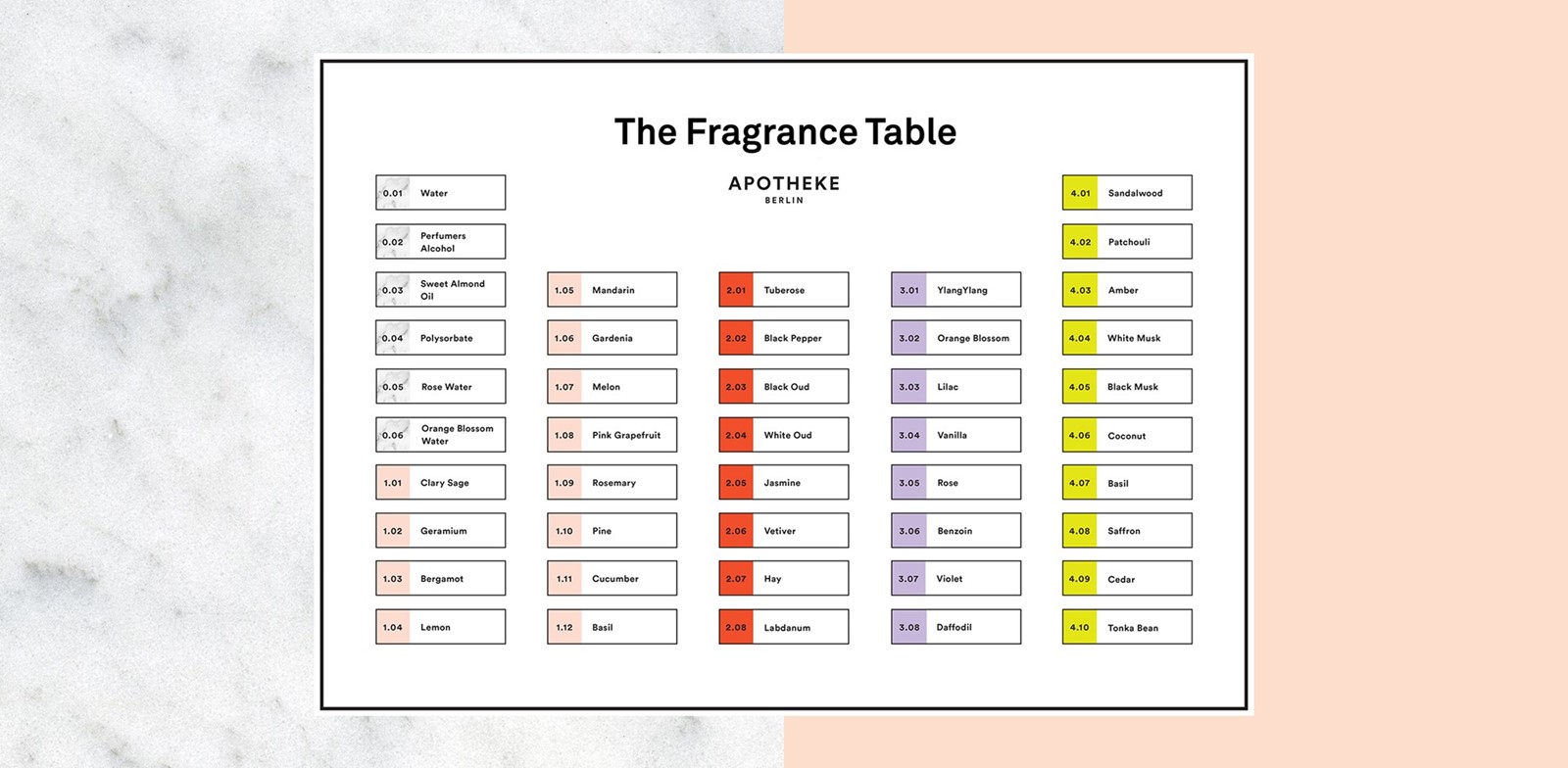

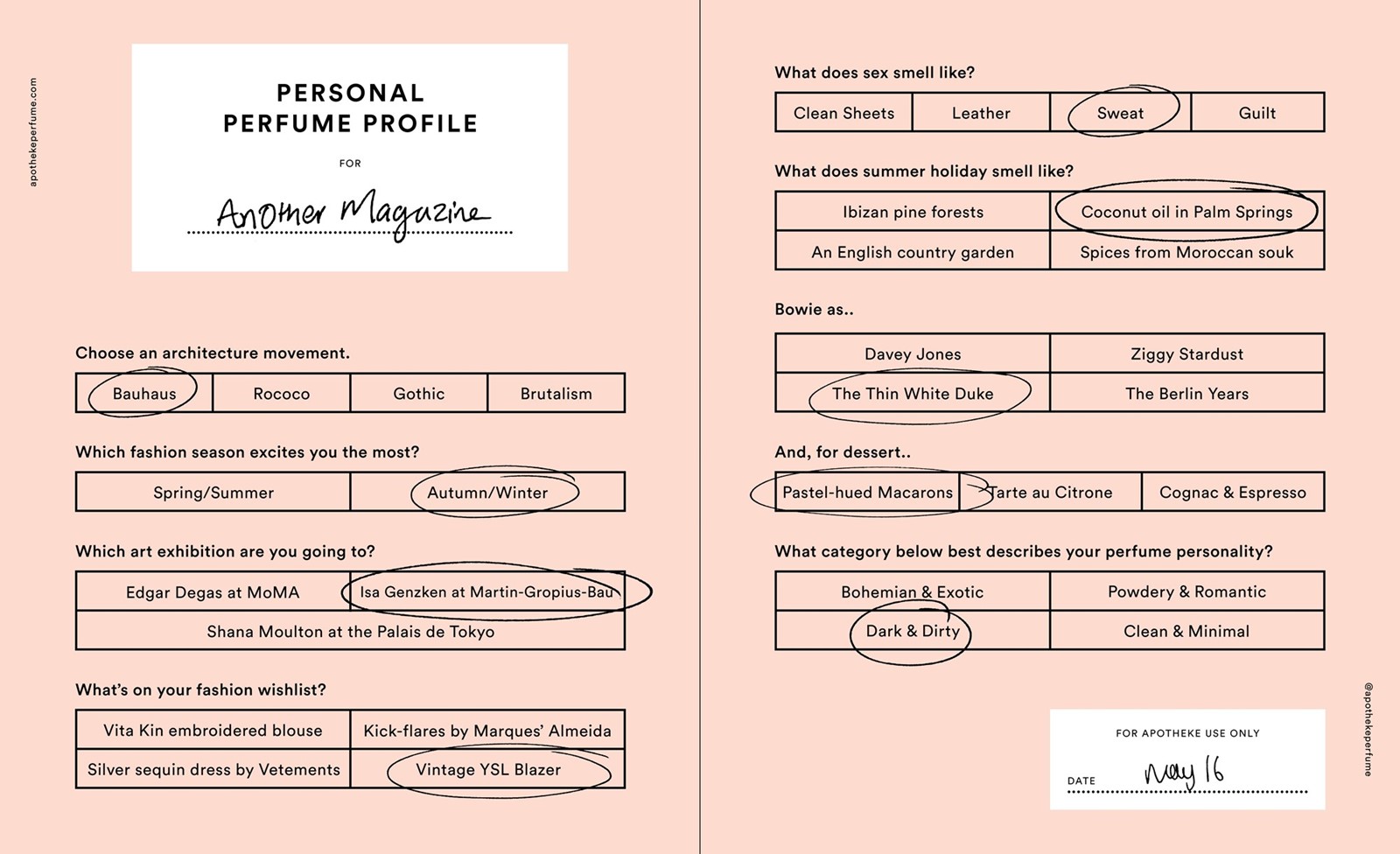

Through word of mouth, Hannan was soon booked to do an all-day schedule of over a hundred olfactory appointments for a London marketing firm, which acted as a soft launch for Apotheke and the first time the made-to-order perfumes, in their medicinal Mondrian-like bottles, were sold to complete strangers. “You can read as many books as you like, but it’s through sitting with somebody and understanding how to build a scent with them that makes it an emotional exchange. I’ve had people cry over ex-boyfriends and tell me about bad relationships with their mother. All of my questions are delving into peoples’ psyche.” In a comforting tradition, Hannan often draws on her female intuition to understand what women want (it’s no coincidence that Jerusalem wall paintings show that as far back as first century B.C., Egyptian perfumers were women, serving the court and the temple). She likens perfume to an extension of our wardrobes, and believes that everybody can be understood through her “four pillars of perfume,” – and that she can identify these almost immediately with her encyclopaedic knowledge of scent. Each one of her pillars are reflected in Apotheke’s elegant branding, which is centred upon four of Hannan’s favourite fashion-inspired colours: Prada chartreuse for the bohemian exotic; Gucci red for the dark and dirty; Luella lilac for powdery and romantic; and Miu Miu blush for clean and minimal. “Often people are one or two and their answers to questions will tell me where they sit, but it’s always collaborative. Some people know exactly what they like, and some people think they’re something and then discover they’re actually something else – especially men.”

AnOther took the test, and the result is a perfume that defines us to the core. Here, Hannan explains her magical methodology and sheds light on her perfume quiz.

Clean and Minimal

Notes: Bergamot, Melon, Lemon, Pine, Clary Sage, Lily of the Valley, Geranium, Gardenia, Grapefruit, Rosemary, Cucumber

“This category is all about fougère, which translates to ‘fern-like’ in French and generally relates to fragrances that are green and clean,” explains Hannan, who cites dry and peppery Calabrian bergamot as a key note. Often citric and herbaceous, these notes pertain to a minimal but soapy feeling, offering a sensibility mutually appreciated by “colonial Oscar de la Renta ladies” (lily of the valley, gardenia, clary sage) and “Acne graphic designers” (lemon, pine, cucumber) alike. Brands such as Aesop fall into this category, which is exquisitely fresh but slight lacking in spirited sensuality – if you answered clean sheets, Isa Genzken, Bauhaus, Thin White Duke, pine forests or tarte au citron, you’ll most likely appreciate these the herbaceous nature of these notes. “This is the type of person that has matching magazines, takes pleasure in freshly sharpened pencils and really appreciates design,” says Hannan, whose combination of pink grapefruit, bergamot and black pepper inspires images of razor-sharp fringes and elegant check chinaware. “AnOther sits between this category and the following, Dark and Dirty,” according to Hannan.

Dark and Dirty

Notes: Jasmine, Tuberose, Honeysuckle, Vetiver, Leather, Tobacco, White and Black Oud, Black Pepper

Although dark and dirty fall into the same overarching category, the two have their own idiosyncrasies. ‘Dirty’ compromises of the animalic scents of creamy white flowers, also known as ‘knicker notes’, whilst ‘dark’ is altogether smokier and leathery. These are the scents that may be hard to stomach for some, but an emblem of sensuality for those gutsy enough. “Jasmine and tuberose are the sexiest of flowers,” explains Hannan, who lists Flowerhead by Byredo, Carnal Flower by Frederic Malle and Fracas by Robert Piguet as poster perfumes for the meaty fleurs. “If you’re not feeling sexy, it owns you, so you need to be strong to wear it – you can’t fake it.” Napoleon famously told Josephine not to wash in anticipation of his return and it’s that yonic appeal that charge these fleshy notes with unapologetic sensuality. As for the tobacco, vetiver, leather and peppery ouds, it takes a perverse pleasure in the slight acridity to these notes to truly pull them off. “The raw essences can be quite offensive, but I love it when someone can appreciate that. Sometimes there’ll be someone that will love raw vetiver, which is gloopy and black, and they gravitate towards the darkness.” YSL’s le smoking and Vetements sequins for a night of hedonism are telling answers, as are skin-scorching coconut oil in Palm Springs, Bowie in his Berlin years, and a preference for cognac and espresso over pudding. “These are the notes that are left over when you’re walking home from a night out, or at your desk after a night of partying. Someone once told me Kate Moss smells of cigarettes and tuberose; that sums it up.”

Powdery and Romantic

Notes: Rose, Violet, Iris, Vanilla, Ylang Ylang, Orange Blossom, Daffodil, Lilac, Benzoin

“All is permitted the rose – splendour, a conspiracy of perfumes, petalous flesh that tempts the nose, the lips, the teeth… ” wrote the 1940s perfumer, Colette. “All is sad, all is born in the year the moment it arrives; the first rose merely heralds all other roses. How confident it is, and how easy to love! It is riper than fruit, more sensual than cheek or breast.”

The delicate aromas of a country garden, especially the rose, are what define this utterly feminine category. “It’s what you’d expect 1950s make up to smell like: floral and creamy,” says Hannan. “This category is the hardest to do right – it often it needs a twist.” Rose, considered the queen of the flowers to king jasmine, is a lynchpin of this sweeter and more playful side of perfume, which might appeal to those that gravitate towards the work of Degas or ornate Rococo architecture. Alessandro Michele’s Gucci, Sophia Webster and Chloé mimic the sensibility of these perfumes, which can be difficult to master without smelling twee. The key is often a combination with another category – a sharp citric twist or dose of warm spice to offset the natural sweetness of these sometimes saccharine notes. “It’s kind of nostalgic and retro.”

Bohemian and Exotic

Notes: Amber, Sandalwood, Musk, Saffron, Cedar, Aniseed, Coconut, Tonka Bean, Basil

For those that seek and worship the sun, the golden warmth of ambergris is like a beautiful piece of jewellery picked up in an exotic marketplace – Oscar Wilde went as far as to say that it stirs one’s passions. “It’s about the scents of the orient,” says Hannan. Spicy musk evokes the sun-kissed luxury of a holiday, creating an aura of bohemianism. Patchouli, which for many is wrapped in memories of the 60s, was actually used in the 19th century to scent Kashmiri shawls and to discourage moths from damaging them. Soon, it infiltrated France and the sweet, rich aphrodisiac qualities began to be paired with rose, vetiver and sandalwood. Perfumes such as Guerlain’s Mitsouku and Shalimar, Etro’s Ambra, Dior’s Poison and Yves Saint Laurent’s Opium evoke the fantasies of tanned leathers and Talitha Getty. Thinking of that Vita Kin embroidered blouse in a Moroccan souk? Chances are you’re at home in Las Dalias with skin that can handle the heavy scents of this category. “People that usually fall into this category usually like a mixture of oils to be mixed like lots of little pieces of jewellery.”

Follow Apotheke Berlin at @ApothekePerfume.