The rapid evolution of the Six+1 came down to a series of serendipitous cultural events, Hannah Rogers explains, but their immutable legacy endures even now

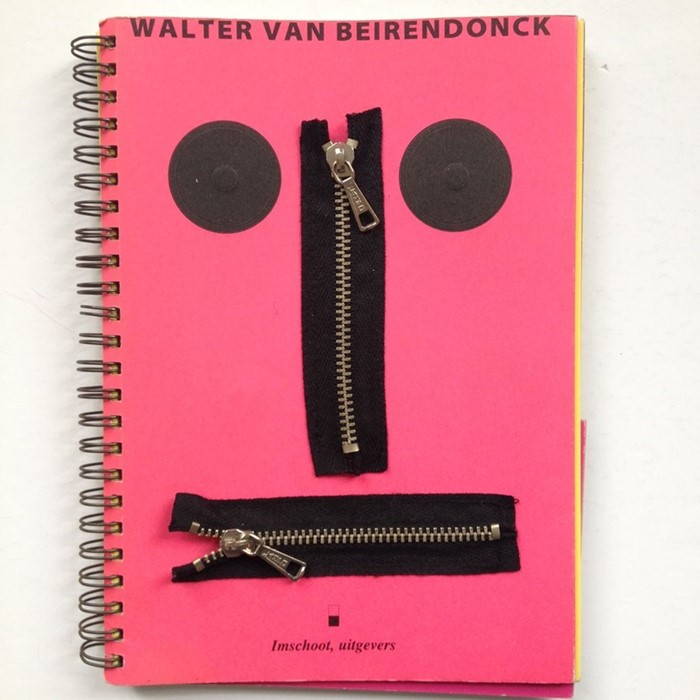

London, 1986. A group of unknown graduates from the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp arrive at the British Designer Show, crammed into a small van, to present their collections. Within just three days, they find themselves stocked at Barneys, Bergdorf and Liberty of London, and propelled into the media stratosphere. Ann Demeulemeester, Marina Yee, Dries Van Noten, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dirk Van Saene and Walter Van Beirendonck become the “Antwerp Six”.

Three decades on, the six young Belgians’ swift journey to global acclaim still captivates the industry. The Antwerp Six – a label conjured up by the press not least due to the difficult pronunciation of their names – remain memorable not so much because of all the six designers individually (some maintained their place in the limelight while some faded), but because they represent the rare phenomenon of a group making an impact on the international stage simultaneously. Though editors have strived to discover a second wave, occasionally thrusting greatness upon groups of succeeding Antwerp Academy graduates, history has not been repeated.

What then, was the magic formula? Coincidence played a role; the talent and personalities of the group and those around them informed every detail of each designer’s collections. The group also had luck on their side historically: at home in Belgium, fashion funding was receiving heavy investment. But, more broadly, the designers were developing in a decade synonymous with vibrancy, creativity and risk-taking. Combined, a perfect storm broke, offering a window into the fashion climate of the 1980s, and raising the question: could that kind of talent ever be cultivated in such a way again?

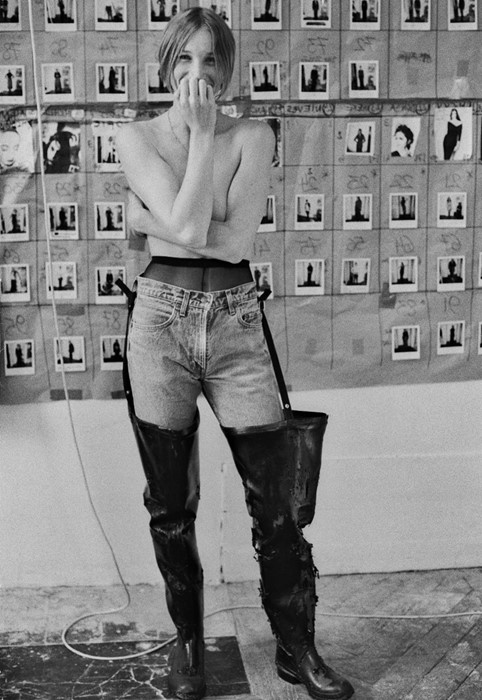

A world away from the filtered, hashtagged sphere in which designers now function, the fashion climate of the 1980s was laced with rebellion, anarchy and consensus-breaking transformation. Youth culture had spread like wildfire through the 60s and 70s, and London had usurped Paris to become Europe’s cultural epicentre. Politically, times were charged: Margaret Thatcher was ruling with an iron fist, America was a financial powerhouse under Reagan, and communism fell in Eastern Europe. Creatively, the scene was electric.

In London, subculture ruled. The city was enamoured with the idea of the independent creative, encouraging young risk-takers to forge their own path, and bringing them together in pounding club and music scenes. In the underground sphere, some of the industry’s most groundbreaking magazines (Dazed & Confused, Blitz and The Face) took shape, all of which was also closely informing London’s fashion scene, which was just beginning to be taken seriously. The British Government suddenly noted the potential of young designers, offering funding, hosting parties and championing the industry; Thatcher herself hosted a number of receptions in Downing Street; London Fashion Week as we know it now gained pace, showcasing a generation of ambitious graduates from the Royal College of Art, Central Saint Martins and London College of Fashion. The 1980s saw designer fashion mature into a financially viable business.

The designers who emerged from this crucible of creativity were making collections informed by social circumstance. Alongside the surge of prosperity, an uglier world existed, and social unrest, terrorist bombings, strikes, high unemployment and the rise of HIV/AIDS also filled the headlines. “Perhaps that stimulated creativity,” said Hendrik Opdebeek, head of menswear for Belgium’s landmark boutique Stijl in Brussels. “Negativity existed in the period. People had to create something to fight against that – to create their own worlds.” Fashion, as it still does, served as a means of both expression and escape.

For the Antwerp Six, these changes in the fashion landscape proved pivotal. On the international stage, there was an opening for young, experimental talent. Economically, businesses had the money to invest and politically, unrest subconsciously provided creative stimulant. London, their choice for debut, was the most open minded of all. But, change is infectious; the climate in Antwerp was transforming too.

Antwerp in the 1980s

1981 was a dramatically significant time for Belgian fashion design. Following a decline in the once prosperous linen industry, Willem Clales, the Belgian minister of economics, launched his “textile plan”. Encouraged by Helen Ravijist, a chairwoman of the Belgian Institute for Textiles & Fashion, the Fashion: It’s Belgian campaign and Golden Spindle competition were set up. Both were designed to grow the fashion industry in Belgium, and to introduce young, talented home-grown designers to major ready-to-wear brands. It was also the year that most of the Antwerp Six graduated, alongside their friend and colleague Martin Margiela. Though Margiela did not accompany the group to London, instead going to work for Jean Paul Gaultier in Paris from 1984, he remains a key member of the graduating class.

The Six+1 frequently won awards at the Golden Spindle competition, and their collections sparked an appetite in Belgian consumers. “I really felt like there was a zeitgeist in that time,” said Sonja Noel, founder of STIJL and early supporter of the Six+1. “In Belgium, we only had the Japanese, French and Italian designers. I really felt that there must be something else, for younger people – and more to the Belgian taste.” The new creative class tapped into nine-to-nine dressing: clothes that you could wear to work, and to go out. “I was looking for something new, and a lot of people felt the same,” she continued. The anti-glamour of the six+1’s designs were instantly popular. Compared to the power-dressing looks from Mugler and Montana, they felt realistic, whilst their deconstruction of gender and body norms subtly subverted the Parisian fashion system. As put by Noel, “their [the collections’] particularity became classic.”

If London had Blitz nightclub to thank for bringing young creatives together, then Antwerp had Cafe D’anvers. “They had huge parties,” said Nicola Vercraeye, a close colleague of Margiela who now runs owns the only stand-alone shop in Belgium. “Antwerp breeded creativity. I would go out in the craziest outfits, from Helmut Lang, Jean Paul Gaultier – tights, lace jackets. Can you imagine?” Warehouse parties also helped to grow the underground scene. “Events were organised by students at the Antwerp academy that you would hear of,” said Opdebeek, “but it wasn’t limited to parties. We were just of the same generation, with the same interests – it was inevitable that we would all meet.”

At the academy itself, healthy competition between the designers spurred talent on. “It is a little like what happens in sport,” Opdebeek explained. “If you’re from the same generation, the same country and are doing the same sport, your competitive nature stimulates each other. It was the same with the designers. Also, because what they designed was entirely different from the other, there wasn’t any direct threat. That’s why as a group they got stronger and stronger, and they didn’t have to worry about being number one.” The Academy’s teaching style, which focuses solely on creativity without regard for commercial viability, also allowed the designers to do as they pleased. “When you leave the course, you know how to design – and nothing else,” said Vercraeye. “That style of teaching undoubtedly helped to breed the designers it did at the time.” The result was a graduating class the transformed the reputation of Belgian fashion, earning the country notoriety for being conceptual, subversive and avant-garde.

The Impact

Though the climate in which the Antwerp Six+1 developed has changed immeasurably, their history still provides lessons for designers today. The group identity promoted through the 80s fell away in the following decade, with the Six+1 developing their own signatures. Their reputations were built not just through their collections, but also through their business practices; the designers avoided grand advertising strategies and worked at their own pace. A sustainable approach was adopted, with an appreciation for less-is-more. Thirty years on, this legacy is evident in the recent reaction to the ultra-rapid pace of catwalk collections, part of the reason for Raf Simons to exit from Dior. That Simons is also a celebrated graduate of the Antwerp Academy is perhaps no coincidence.

Many have argued that the advance of digital has swept away the opportunity for designers to create anything truly new, as our swipe-happy culture encourages the recycling of ideas. “The way we lived will never come back,” said Vercraeye. “I wouldn’t say fashion is dead, but it’s not as alive as it used to be. People will always need something to wear, but the industry will be different. I like to see this positively. We’ve reached peak internet. Even if you pick up old ideas you can make them new, and more for now.” This in itself is a new challenge for our graduating designers, who face a market that appear to have seen it all.

That market has changed in other ways, too. Noel pointed out that conservatism has swept the youth of today, with the rise of e-commerce encouraging safer buying choices. “They [the young] are refusing extravagance,” she said, “and you need a little bit of that to come out with new things. Now, young people all want to be like each other, to be part of a group. But I am sure there will be a time where there will be more individuality, more confidence. I miss that.”

Perhaps the greatest lesson to learn from the rise of those Belgian creatives is the importance of a designer’s confidence in their artistic vision. In a climate saturated with images and information, critical and independent voices are the most valuable stock of all.