Hannah Tindle examines the aesthetic codes that define the spectacular yet sinister 1986 film: from colour palette consistency to the abundant baring of flesh

“She was a flower with a psychic antenna and a tinsel heart. Not many girls could dress as casually as she did,” says the dulcet voiceover of handyman and would-be writer Zorg, remarking on his lover’s provocative sartorial displays. The tinsel hearted woman in question is our on-the-verge-of-insanity protagonist Betty, the title character of Jean-Jacques Beineix’s third work exemplifying the genre of Cinéma du Look, a 1980s movement in film that favoured self-conscious aesthetics, lush colour palettes and vivid tales of doomed young lovers. And indeed, Betty Blue clearly encapsulates all of these tropes.

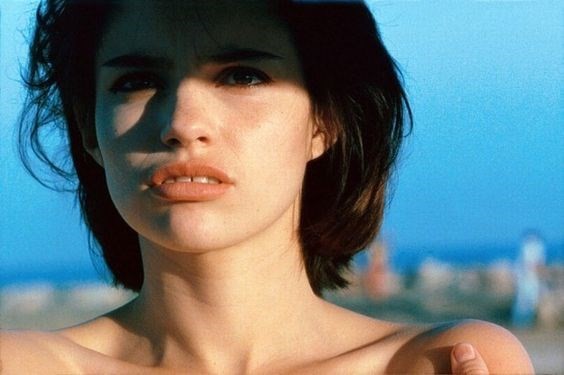

Played by the flawlessly cast, toothy and wayward Béatrice Dalle (who truly does turn out some iconic aesthetics throughout) and Jean Hugues-Anglade respectively, the film chronicles Betty and Zorg’s tumultuous relationship; a jolty narrative combining slapstick humour and romanticism, peppered with hints of their sinister road ahead. Despite various prestigious award nominations - an Oscar, BAFTA and Golden Globe – it was critically panned at the time of release for supposedly lacking in gravitas and favouring stylistic spectacle. However, Betty Blue ultimately examines a problematic relationship between women’s perceived and experienced madness, demonstrating that style and substance can be inextricably bound.

1. Wear very little (or nothing at all)

In a less than favourable review, Roger Ebert noted: “Jean-Jacques Beineix has made a film that he thinks is about romantic obsession, and I think is about skin”. Yes, there may be instances where Betty answers the door knickerless wearing a tank top as a dress, and aggressively displays herself to Zorg’s disgruntled boss. And yes, the film’s opening scene involves the couple completely nude, intertwined mid-sexploit – a heavily repeated occurrence. If Betty isn’t completely naked, she’s either wearing an apron and nothing more, or an off-the-shoulder scarlet dress revealing the entirety of her décolletage and a great deal of her legs. At times, it can feel as though we are witnessing the unjust equation of women’s liberated sexuality and freedom of self-expression through clothing with lunacy. But simultaneously, there is often a sense of realism in the frequent amounts of female and male flesh on show, portraying the shared intimacy that comes with shedding our layers of apparel, à la Adam and Eve.

2. Accessorise and accent with flashes of red

Betty’s scarlet dress (notably featured in a scene where she sits atop Zorg’s car “warming her ass”) is not the only poignant use of the colour in Betty Blue. Punches of the shade representing danger, desire and strength are visible in her strikingly-1980s shoes, earrings, bangles, cardigans and lipsticks. Notably, most of the other characters in the film wear it in some form: from her best friend carrying crimson flowers with matching boots, to the claret uniforms at the pizza parlour that she and Zorg reluctantly work at (Betty’s in the form of a backless waistcoat-meets-tuxedo, for reference). In the aftermath of Betty gouging out her eye – the action of which the director does not permit us to see – we are left with clues to what has occurred. Notably, a single red leather mule is visibly strewn on the floor of the apartment amidst painterly, bloody handprints.

3. Be unapologetically dramatic with your interior decoration

“It’s dark in here! It stinks! It’s ugly! I’m fed up! I can’t breathe in here! I’m going to fix your house up good so I can breathe.” Clearly, Betty is displeased with the dingy beach hut that she inhabits with Zorg in a sandy, dilapidated seaside community. Instead of consulting an interior decorator as one might do, she takes matters into her own hands and brutally throws boxes of household objects out of the window, pushes bowls of apples and crockery off tables and in the midst of her frenzy, discovers Zorg’s unpublished writing and concludes that this is his true calling. A few days later, finally she has had it; a fresh lick of paint just won’t do and setting fire to the entire shack is obviously the only solution. The lovers hurriedly up and leave for Paris, abandoning their old life in the ashes.

4. Make-up choices should be reflective of the human psyche

It’s the first time Betty and Zorg meet in daylight. Their relationship is new, there is optimism in the air and Betty’s make-up is impeccably applied; the elusively seductive combination of a tangerine eye shadow and a red lip. Later, when Betty discovers that her suspected pregnancy was a false alarm, it finally pushes her over the edge into a spiral of heartbreak and madness. Zorg arrives home to find Betty at the dining table, trembling; her hair is unkempt and clown-like makeup is smeared over her face in a clear directorial homage to Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? In an act of utter despair, Zorg takes a bowl of pasta from the table and rubs his face with sauce to mirror Betty’s dishevelled visage and mental state, before kissing her passionately.

5. Pay respect to the sartorial identity of your lover

Zorg remains devoted to Betty throughout her mental and physical decline, endeavouring to provide support in whichever way he can. During this time, in a bizarre turn of events – and perhaps as a coping mechanism for his grief – he decides to rob a bank in ‘Betty drag’; her signature red dress, sunglasses, earrings, white court shoes and dark haired wig all forming the basis of his disguise. After Betty’s hospitalisation, he is forbidden from visiting due to loud protests over her poor treatment, so takes matters into his own gloved hands by sneaking into the sanatorium in the same bank robbery costume. Dressed in tribute to his incapacitated lover, he cries, “we were meant for each other, no one can ever separate us, no one, ever!” before smothering Betty with a pillow.