The things we think we know about Christian Lacroix are restricted to the what, and the when, rather than the why. Lacroix is the designer whose bubbled and puffed volumes defined the latter half of the 80s – a riposte against the aggression of the decade’s shoulder pads, aerobicised bodies, and paralysing good taste. Lacroix’s clothes, by contrast, were fun, flirtatious and frilly, characterised by coquettish layers of petticoats abbreviated, like a Western saloon wench’s, about the thigh. He had a fondness for the high-gloss of duchesse satin, clashing together various colours – like his signature shades of shocking pink, hellfire orange and a sickly gooseberry chartreuse – in a single outfit. In all likelihood, those jarring colours would then be paired with further hues, or juxtaposed against brocade or embroidery, perhaps swooshed over with an old-fashioned fichu or apron, the fabric knotted up into a bow, or a bustle, or a big fat cabbage rose. Christian Lacroix’s style was about excess and abundance. It was, simply, about more.

That urge for more, perhaps, underscores part of the “why” behind Lacroix – certainly when it comes to the reason he was popular back then, and seems to be now. Because 30 years after his eponymous haute couture house was founded and almost a decade after it closed, Lacroix is back with a vengeance. Not the man himself. Since his business folded in 2009 – it never made a profit – he’s been happily holed up designing opera costumes. “Costume is my favourite thing,” Lacroix confessed to me when I met him in 2013. “Not fashion.” Coming from a designer who piles up crinolines, corsets and passementerie in a manner not seen since the court of Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, that was no great surprise. What is surprising is the odd domination of Lacroix in the Spring/Summer 2017 collections of a litany of designers – young, old, established and new.

Perhaps that should be Lacroix-esque, or Lacroix-ish, their lines inspired by, rather than derivative of. We’re certainly not talking a piecemeal resurrection, nor a pulling-out of Lacroix’s “pouf”, the bubbly skirt the British more plainly called a puffball and which defined late-80s party-gear at all levels. Although, truth be told, young socialites have already been buying (and wearing) archive Lacroix pieces. Lauren Santo Domingo, a moneyed New York socialite, wore a bustle-bubbled dot-polkaed dress Lacroix designed for the house of Jean Patou – in 1985 – to last year’s wedding of Giovanna Battaglia and Oscar Engelbert. It’s fitting: Santo Domingo is rail-thin, a modern-day incarnation of the “social X-rays”, as Tom Wolfe’s Sherman McCoy dubbed them in The Bonfire of the Vanities who, “To compensate for the concupiscence missing from their juiceless ribs and atrophied backsides,” turned to fashion designers. Namely, Lacroix.

“Humour and parody, kitsch and cliché. Lacroix’s clothes had all of that. What they also had was an instantly recognisable style” – Alexander Fury

To many, Lacroix’s dresses belonged on their own bonfire at the end of the vanities of that decade, epitomising the worst of 80s excess – the “more” I talked about before. A Christian Lacroix dress was a junk bond, a corporate raider, a chintzy interior by Mario Buatta, perhaps decorated for Donald and Ivana Trump. Maybe it’s precisely that which is drawing designers back, perversely, to Lacroix’s oeuvre. So wrong, it’s right, for right now. The influence seeping through to designers is varied, and multilayered. It could be as simple as a shoe, with a Louis heel flaring like a toilet pedestal as it touches the floor, or with satin ribbons crisscrossing around the ankle. Some clash colours with Lacroix-levels of abandon, like virulent violet against a sickly Pepto-Bismol pink, or splash overblown roses or multicoloured dots on evening dresses. A few have gone all out with embroideries, soutache braid and fringe, ruffling voluminous skirts to points just shy of poufs, and inflating sleeves to the size of crash-helmets. They’ve even seized on Lacroix’s beloved duchesse satin to create the kind of extravagant evening dresses we haven’t seen since 19 October, 1987. That was the trading day dubbed Black Monday, when the bottom fell out of the boom and the Dow Jones dropped 22.61 per cent in value (still ranking as the largest one-day percentage decline in its history). Lacroix’s hitherto rising star began to plateau, if you’re putting it politely. At press conferences coinciding with an October New York benefit to launch his first ready-to-wear collection, staged just days after Black Monday – and, ironically enough, held in the World Financial Centre – Lacroix was purportedly asked two questions, again and again: how do you sit in a bustle? And who in the world will buy your clothes?

They had bought, of course. Across the way from Le Bristol on Paris’ rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré, sits a hôtel particulier, one of those fancy French mansions adapted, in latter decades, for business use. It’s boarded up now, but once, not that long ago, it was Lacroix’s, decorated in his Dantean palette and studded with coral and wrought-iron furniture by Élisabeth Garouste and Mattia Bonetti, a point of call for rich women, who came to be richly dressed. When Lacroix was open, it was thronged – the first customer to the new couture house was Madonna. But Lacroix’s supposed egalitarian ready-to-wear never galvanised the support his elite haute couture elicited, while his perfume, couture’s traditional mass-market, mass-appeal money-spinner, failed on all those counts – launched in 1990 and withdrawn just a year later. It was, prophetically, named “C’est La Vie!” Translation: “That’s life.” Maybe it’s all a matter of timing: Lacroix’s seemingly inexorable rise was in direct correlation to the burgeoning fortunes (fiscal and social) of the decade’s nouveaux riches – his fall was, too. When Lacroix became chief designer at the dowdy Paris couture house Jean Patou in 1981, it was just as the decade’s high earners began to soar. And there Lacroix delivered exactly what the age demanded: more, more, more. “Everyone had forgotten Patou,” he said, “so I had to shout for attention.”

Lacroix did so by creating larger-than-life clothes for those larger-than-life Yuppie pay packets to be spent on, clothes that wound up looking like postmodern caricatures of couture, overblown in volume, oversaturated in colour, and wantonly over-decorated. Post-feminist women delighted in reclaiming the overtly feminine – petticoats, corsets, stockings, all the trappings of pre-feminist eras now ironically reappropriated. Appropriation, indeed, was key to Lacroix’s approach. He originally trained in costume history, to become a museum curator, and subsequently created clothing that could feel less designed, more curated from a variety of disparate sources. Lacroix telescoped together eras and styles – an 1890s sleeve, a skirt from the 1700s, a waspwaisted guêpière corset from Christian Dior’s New Look – maybe juxtaposed in a single outfit, recoloured with a palette straight from Ettore Sottsass’ Memphis movement. In fact, what Lacroix was doing was akin not only to the design of Sottsass, but the architecture of Frank Gehry, the art of Jeff Koons and the product design of Philippe Starck. All drew on postmodernist theories, referencing and parodying art and design history, adding elements of kitsch, creating luxury products (even art became a consumable in the hands of Koons) with a sense of humour, black or otherwise.

“When Lacroix was open, it was thronged – the first customer to the new couture house was Madonna” – Alexander Fury

Humour and parody, kitsch and cliché. Lacroix’s clothes had all of that. What they also had was an instantly recognisable style. If the position as pioneer of the shoulder-pad was hotly contested in the 80s – Armani, Montana and Mugler all jockeyed with Yves Saint Laurent for the distinction – Lacroix’s idiosyncratic style could not be disputed. While the puffballs, whose authorship is attributed to both his pouf and to Vivienne Westwood, for her minicrini, the rest is pure Lacroix, often imitated but never equalled: silhouettes rounded, proportions occasionally clumsy or ungainly, but intentionally so. He may balance a giant sleeve on a tiny bodice, to create a discombobulating, disorientating effect. The same feeling was evoked by the often-unnatural movements of his clothes – the rigid sway of a balayeuse (“road-sweeper”) skirt, tightly trussed in salmon taffeta and stiffened into a carapace about the body; or by the seemingly random contrasts of decidedly unharmonious colours, generally strident and pure, like paint squeezed straight from the tube.

Lacroix also had a fetish for millinery, with a predilection for the ludicrously undersized or the gargantuan, and a love for the south of France, its arcane folk-dress influencing the costumes he devised for his clientele. Just as the dress of les Arlésiennes – the women of Arles, Lacroix’s Camargue hometown – are anchored by name to the town, and by silhouette to the 18th century, so Lacroix’s creations are folk-costume for the turn of the 20th century, distinct to Paris and the 1980s. It could have been born nowhere else, and at no other time.

That’s all the when, and what. But tackling the “why” of Christian Lacroix – and of next season’s latent Lacroix-isms – is another matter. Why does today chime with back then? Why are designers resurrecting these styles? Perhaps it’s the political strife and conservatism which seems, conversely, to be forcing fashion in the opposite direction. When the outlook is grey, the impulse is to grasp at colour, frivolity, exuberance and eccentricity. It’s something the French are particularly good at: look at the – entirely accurate – fashion plates of women walking around with powdered hair piled high with miniature windmills and rigged frigates in the 1770s, before the monarchy was deposed and executed. Those hairstyles, incidentally, were also called “poufs”, just like the ones Lacroix produced on the edge of another collapse of society as we knew it.

Are we on the brink of a collapse today? With Britain’s seemingly imminent exit from the European Union and the election of Donald Trump, many would argue the volcano whose lip we’ve been dancing on has already erupted. Then, there’s the financial stuff – not just the plummeting value of the pound, but the crash of the Chinese yuan to record lows, the bottoming-out of the Brazilian real (and its knock-on effect, as the largest single currency, throughout Latin America), and rumours of recession at every turn of every newspaper page. They’re all having an impact on the fashion industry’s bottom line too, as well as the pockets of the women who actually wind up buying these clothes.

“There was no darkness or sobriety in Lacroix’s world, as fizzy and effervescent as champagne. It was an exercise in extreme fantasy and make-believe” – Alexander Fury

In fashion, there are two reactions to those kind of socioeconomic extremities: to tough it out and reflect the harsh, even brutal reality; or to retreat into fantasy. Neither is right nor wrong, they’re merely different responses, the equivalent to nature’s fight or flight. Despite the cynicism with which observers now look back at the styles of Lacroix, the designer’s own intent was honest and innocent, ludique. There was no darkness or sobriety in Lacroix’s world, as fizzy and effervescent as champagne. It was an exercise in extreme fantasy and make-believe, in the seductive power of fashion as a dream. “This was a dream,” Lacroix has told me of his career in fashion. “It was not connected to reality, it was not something to be sold.”

Lacroix’s debut generated fever-pitch attention: in the crush to get into his show in Paris’s Hotel Intercontinental on 26 July 1987, an Italian fashion editor fainted. She had to be helped out over the heads of the press. Attention is an interesting concept: these are clothes that demand it, grabbing at the eye. In a digital landscape saturated with media, perhaps that is why designers are drawn to these Lacroix-isms – to help make their own sartorial statements resonate. “Everything must be a kind of caricature to register,” said Lacroix, shortly after his debut. “Everything must be larger than life.” Could any statement be more true of the clothes needed to arrest the deficit attention spans of contemporary fashion watchers?

There’s one word that hasn’t yet been used in this discussion of Lacroix: joy. It is all-important, when it comes to the “why” of Lacroix then, and now. Not just because Joy is the name of the perfume that made Jean Patou’s fortune, and thus enabled Lacroix to begin designing clothes in the first place, but because that is, ultimately, what those clothes were all about. The simple joy of creativity, the joy of craftsmanship, a joy in wearing these extreme, amusing clothes. And the joy, also, of fashion, pure and simple. There’s something joyously “fashion” about the season’s fixation with these Lacroix-isms. Like Lacroix’s own designs, they have resulted in clothes that aren’t especially easy. They’re probably not that easy to make, given their complex construction; they’re certainly not easy to buy, with the prices all that work necessitates; and, perhaps, they won’t be that easy to wear, undoubtedly far less easy than an anonymous T-shirt or skinny jeans. But with their exaggerated silhouettes and sumptuous fabrics, their jumble of decoration and colour, they are very, very “fashion”, almost stereotypically so. And they’re easy to read as such.

These are clothes that take neither themselves – nor the industry bubbling with turmoil and uncertainty, like the wider world around them – too seriously. They’re restoring something of fashion’s fun. They make you want to get dressed in the morning. That’s why designers design them, that’s why women buy them. It’s why we all fell in love with fashion in the first place. Who could ask for anything more?

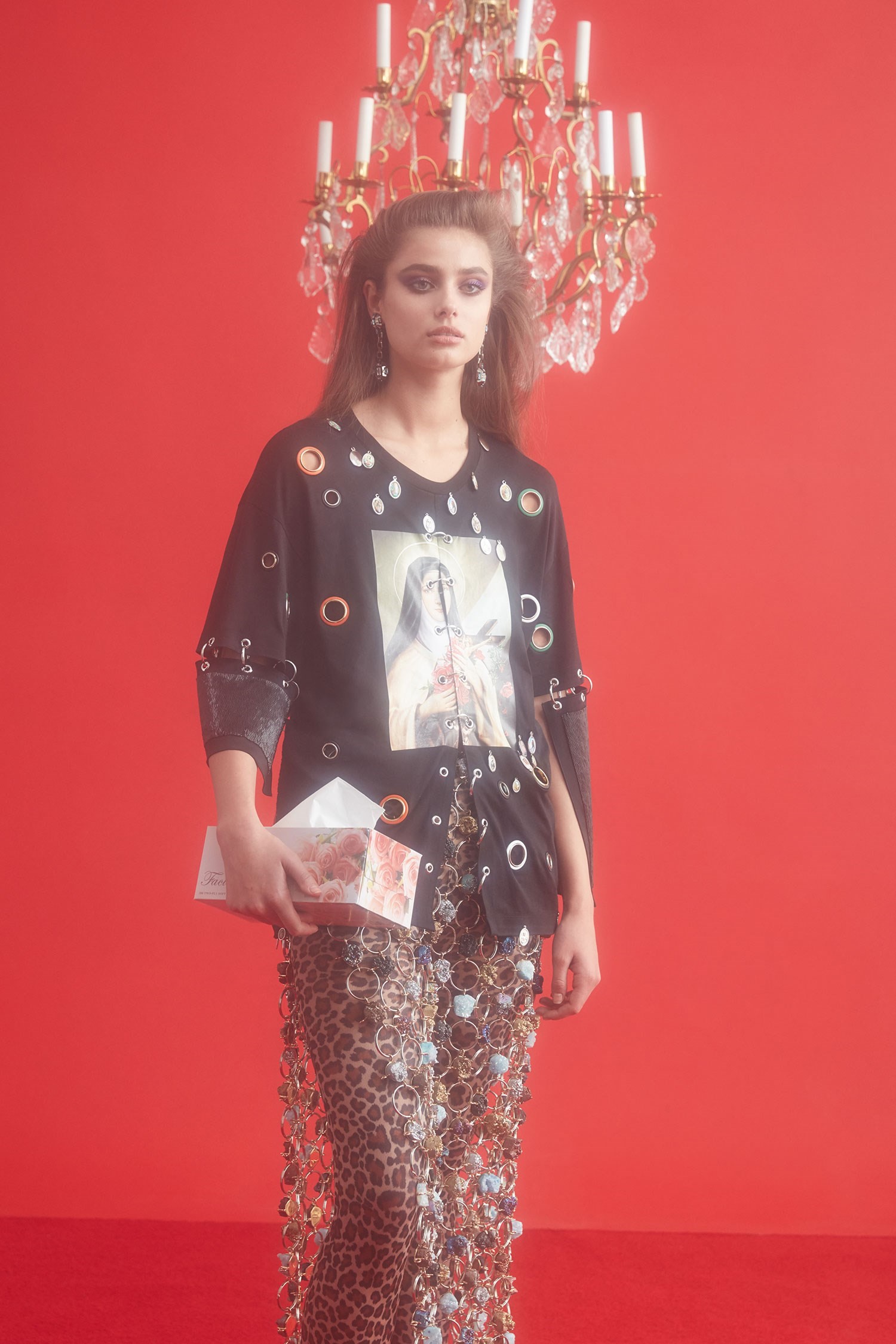

Hair Tamara McNaughton at Streeters; Make-up Susie Sobol at Julian Watson Agency; Models Alicia Burke at Supreme Management, Jessie Bloemendaal at Women Management, Sora Choi at Wilhelmina NY, Taylor Hill at IMG; Casting Noah Shelley at AM Casting; Set design Andy Harman at Lalaland; Manicure Maki Sakamoto at The Wall Group; Digital tech Jonathan Nesteruk; Lighting design Christopher Bisagni for Christopher Bisagni Studio; Lighting design assistants Will Engelhardt, Alessandro Magi, Brent Lee; Styling assistants Rosie Arkell-Palmer, Kirsten McGovern, Jessica Gerardi, Marta Stella; Make-up assistant Ayaka Nihei; Post-production Two Three Two; Production Felix Frith at Artist Commissions.

This article originally appears in AnOther Magazine S/S17.