A show of Marlow Moss's work at Tate Britain brings an influential artist and gender-defying provocateur back to the forefront of art history

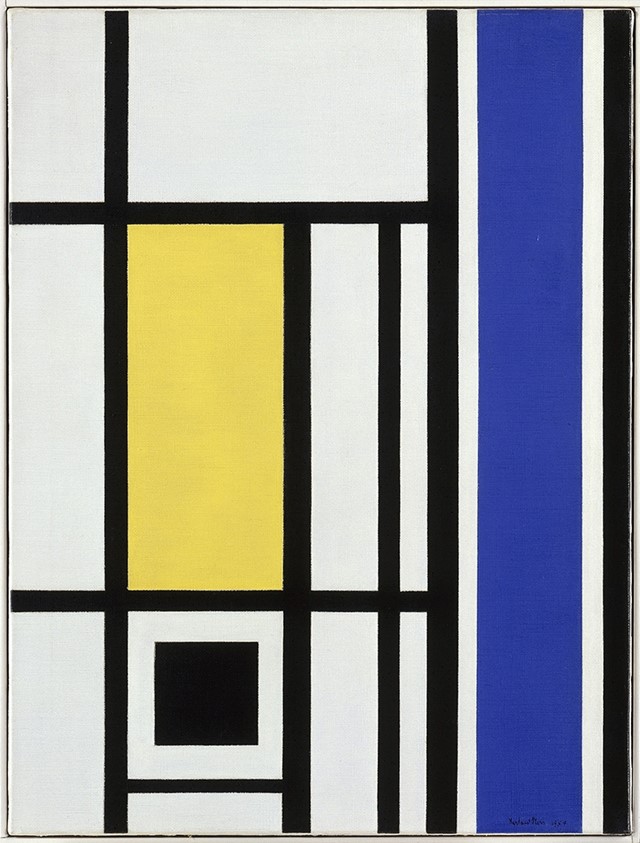

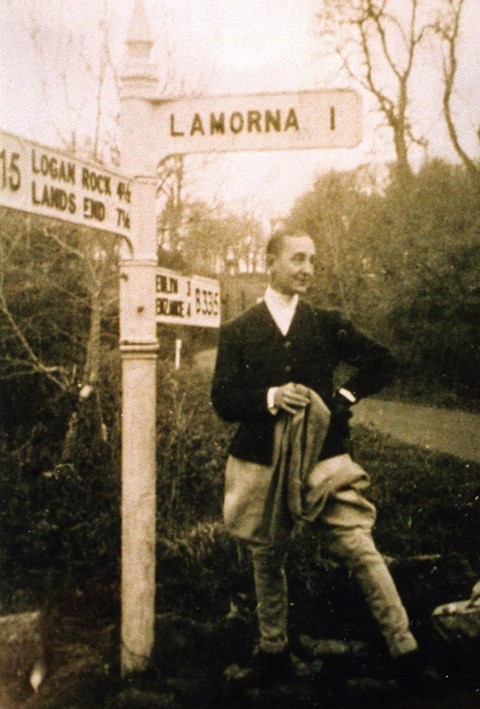

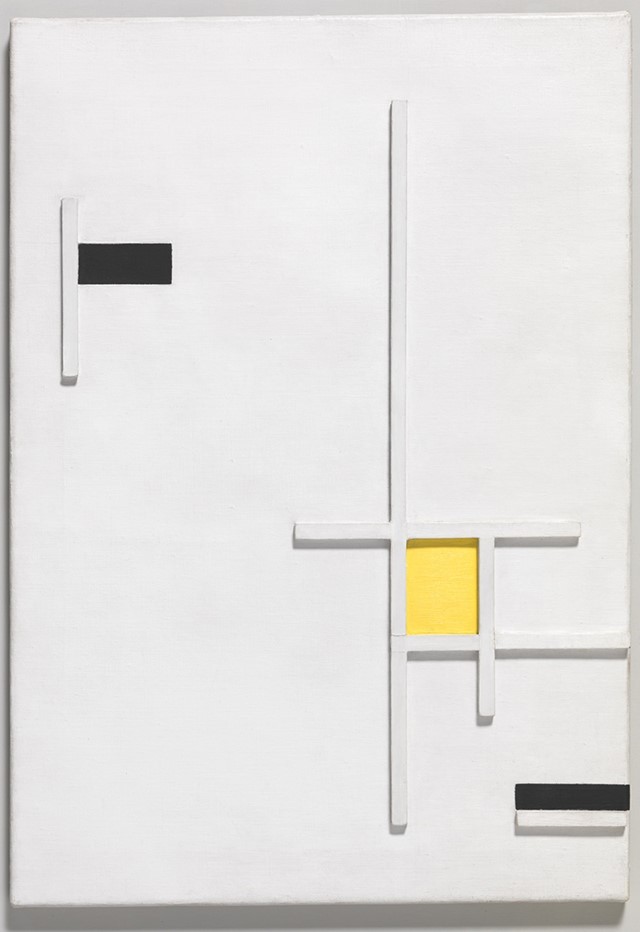

In life and in posterity, British artist Marlow Moss is the invisible woman. In photographs of her, for instance, with tightly cropped hair, dressed elegantly in jodhpurs with a pastel-coloured cravat tied high around her narrow throat, she uses clothes to conceal her gender. Today online, if you ever see her linear, abstract paintings and reliefs, you might mistake them for the work of the more revered Dutch painter, Piet Mondrian. Like so many women, Moss has been written out of art history.

All this is about to change. A new exhibition opening at Tate Britain this month will show Moss to be one of Britain’s most important Constructivist artists. Moss was a radical lesbian and Drag King. Moss was no copycat.

In an internet age, where we are forced to make immediate visual comparisons, our ability to appreciate the integrity of art like Moss’s has been blunted. Google leads us to superficially similar but fundamentally disconnected images. On Instagram and Tumblr we are locked into an infinite, indefinite scroll. No image online is ever read in isolation and when searching for the works of Moss, her art exists as tiny pixels within a pre-constructed environment, eternally flanked by Mondrian’s canvases and the gender-blending portraits of French artist Claude Cahun.

"Moss was one of Britain’s most important Constructivist artists...a radical lesbian and Drag King. Moss was no copycat"

Born in Richmond in 1890, Moss is thought to have discovered Impressionism and Cubism while studying at the Slade. In 1927 she moved to Paris and met her lifelong partner, the Dutch writer Antoinette Hendrika Nijhoff-Wind. It was Nijhoff who introduced Moss to Mondrian; his neo-plasticism had reached its apogee and Mondrian, in turn, became intrigued by Moss’s approach to composition. She had studied the writings of mathematician Matila Ghyka whose philosophy was based on the Pythagorean principle that the universe is founded on numerical relationships.

In 1932, on exhibiting Composition in White, Black, Red and Grey, Moss received a written request from Mondrian to explain her use of the double line. She cited three basic reasons. (1) Single lines produce an impression of planar surfaces; (2) single lines render the composition static; and (3), double, or multiple, lines have a dynamic effect by ensuring “a continuity of related and interrelated rhythm in space.” Persuaded, Mondrian employed the double line the same year.

Moss went on to become a founder member of the Abstraction-Création group and at the beginning of World War II would leave France to live near the fishing village of Lamorna Cove in Cornwall. There, she was accepted as an eccentric, often seen riding on horseback to market, the Casey Legler of her time. However, much of her early art had been destroyed in the war. At her death in 1958, her estate was left to Nijhoff's son, Stefan, a Man Ray-trained photographer who, in turn, left it to his partner, who has seldom shown the work since.

After she died, her paintings were shown at London’s Hanover Gallery. In the catalogue, the Belgian painter Michel Seuphor writes gracefully about how the legacy of an artist should be measured. It is a lesson today to anyone desperate for their 15 minutes of fame: “Many are called, few are chosen. We must wait the death of the artist, and often much longer, to know whether his name will endure. Early success is no longer a guarantee of survival. If the choice of posterity is influenced by patient work, purity of conception, and perseverance, then Marlow Moss will not be forgotten.”

Marlow Moss is at Tate Britain from September 29 to March 22.