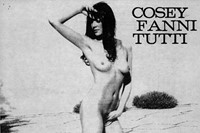

Once decried as a “wrecker of civilisation”; since hailed as one of the most important musicians and artists of the last 40-odd years, Cosey Fanni Tutti is an artist whose output has steadily, defiantly come to inform a generation of practitioners – not only in the work they make, but in more subtle ways around how we think and live. Approaches to collaboration, sound, improvisation, sex, love, what it means to be a woman: it’s not a stretch to see how all these things, and more, have been moulded by Tutti.

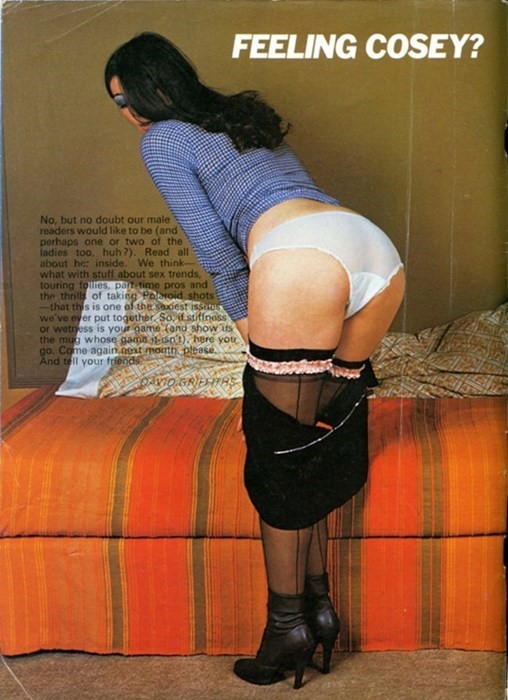

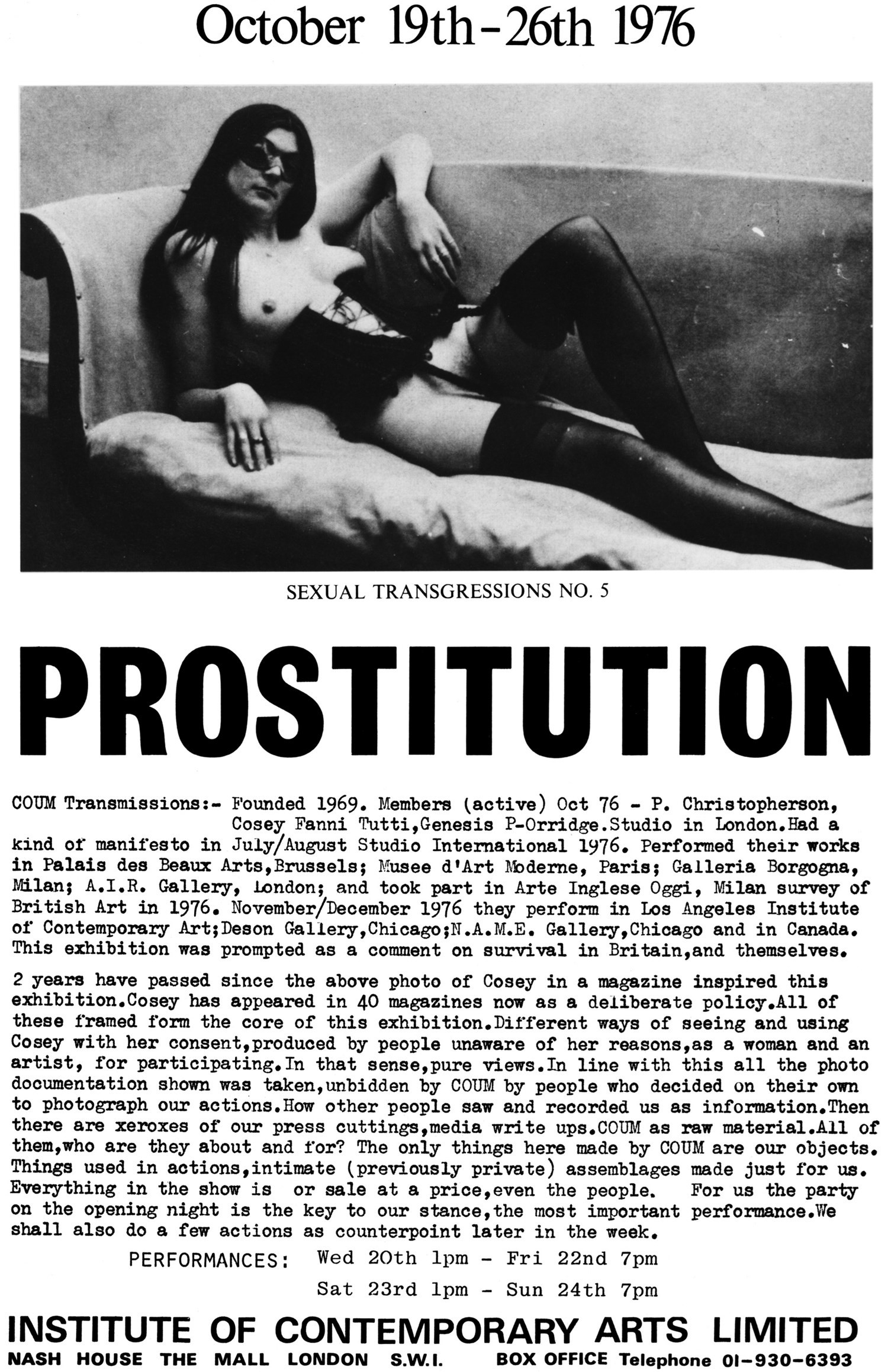

Hers is a tricky life to neatly summarise, but in short, she was born Christine, in Hull, where in 1969 she was a founder member of performance, visual and art and music collective COUM Transmissions. It was with that group that the aforementioned civilisation-wrecking came into play, thanks to the work she created for the Prostitution show at London’s ICA in 1976. The exhibition examined ideas around porn and sex work, and showed her images from modelling in sex magazines and films. Ironically, in a show that looked to open a dialogue around women and the sex industry, her images were hushed behind a curtain and mostly hidden from public view, met with media, and even parliamentary outrage. Following COUM, Tutti co-founded Throbbing Gristle – the band that birthed industrial music – with (her now partner of more than 40 years) Chris Carter, Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson and Genesis P-Orridge. Since then she’s made some truly iconic (not a word used lightly) music as Chris and Cosey, and Carter Tutti, and more recently as Carter Tutti Void with Factory Floor’s Nik Void, alongside Carter.

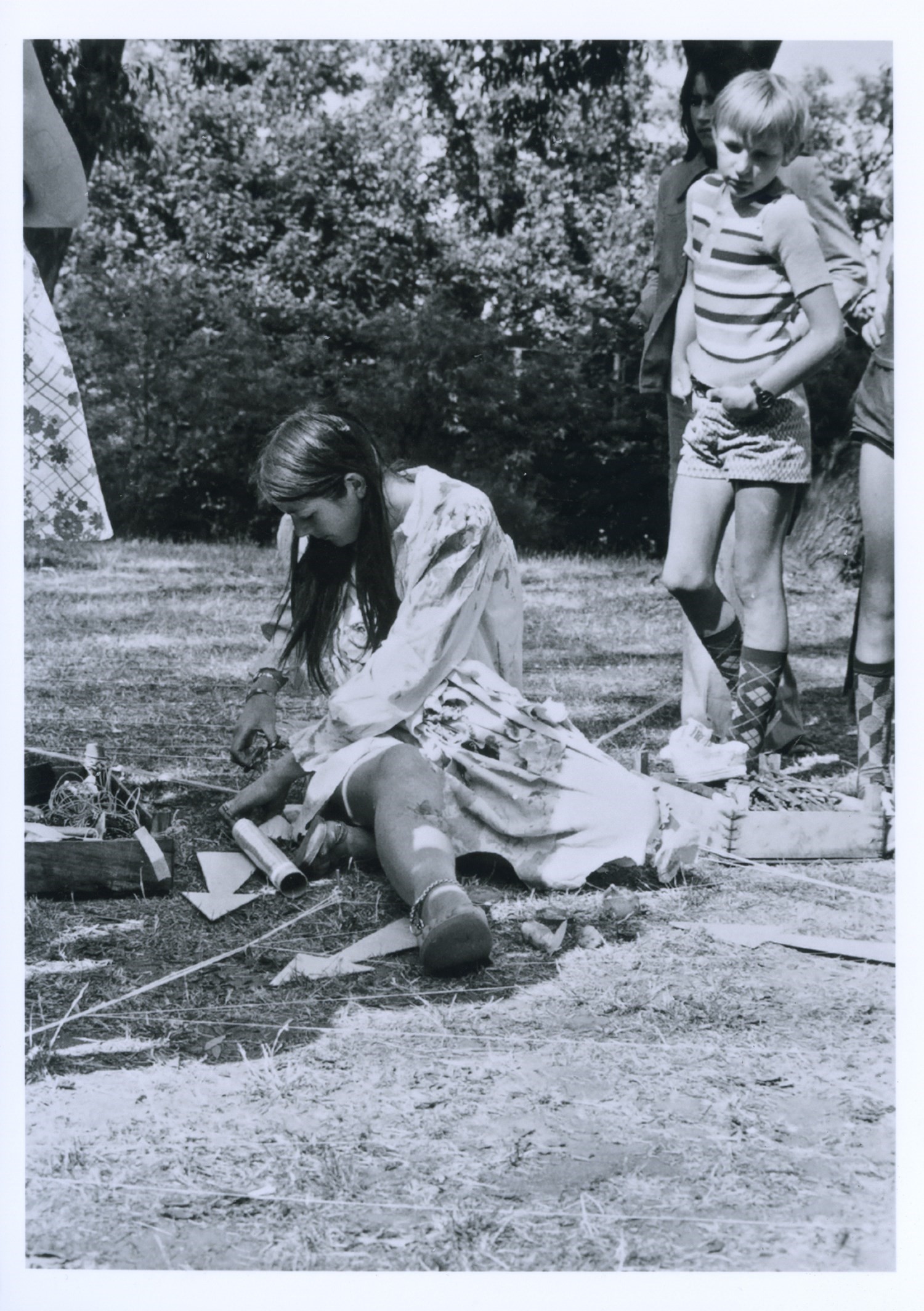

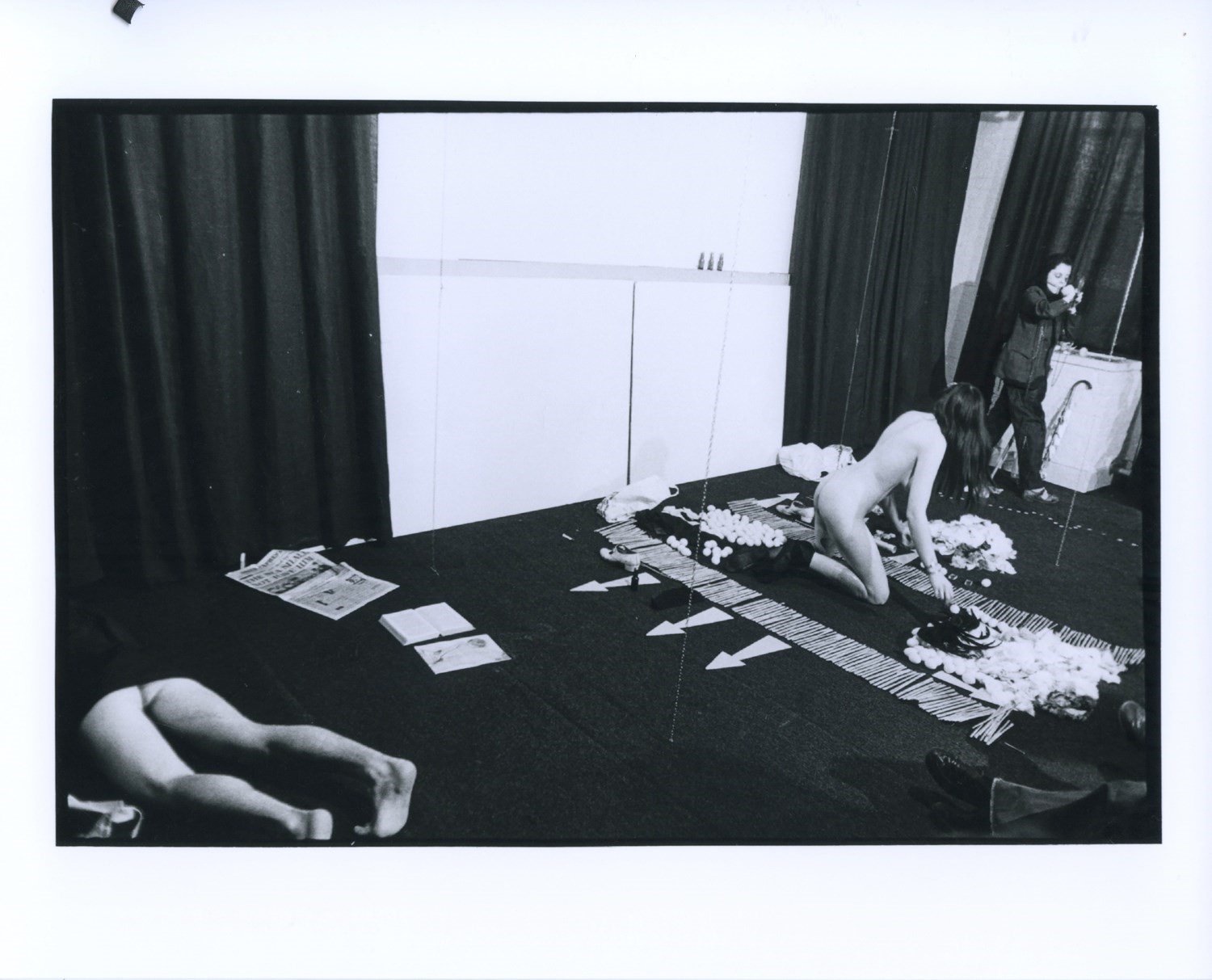

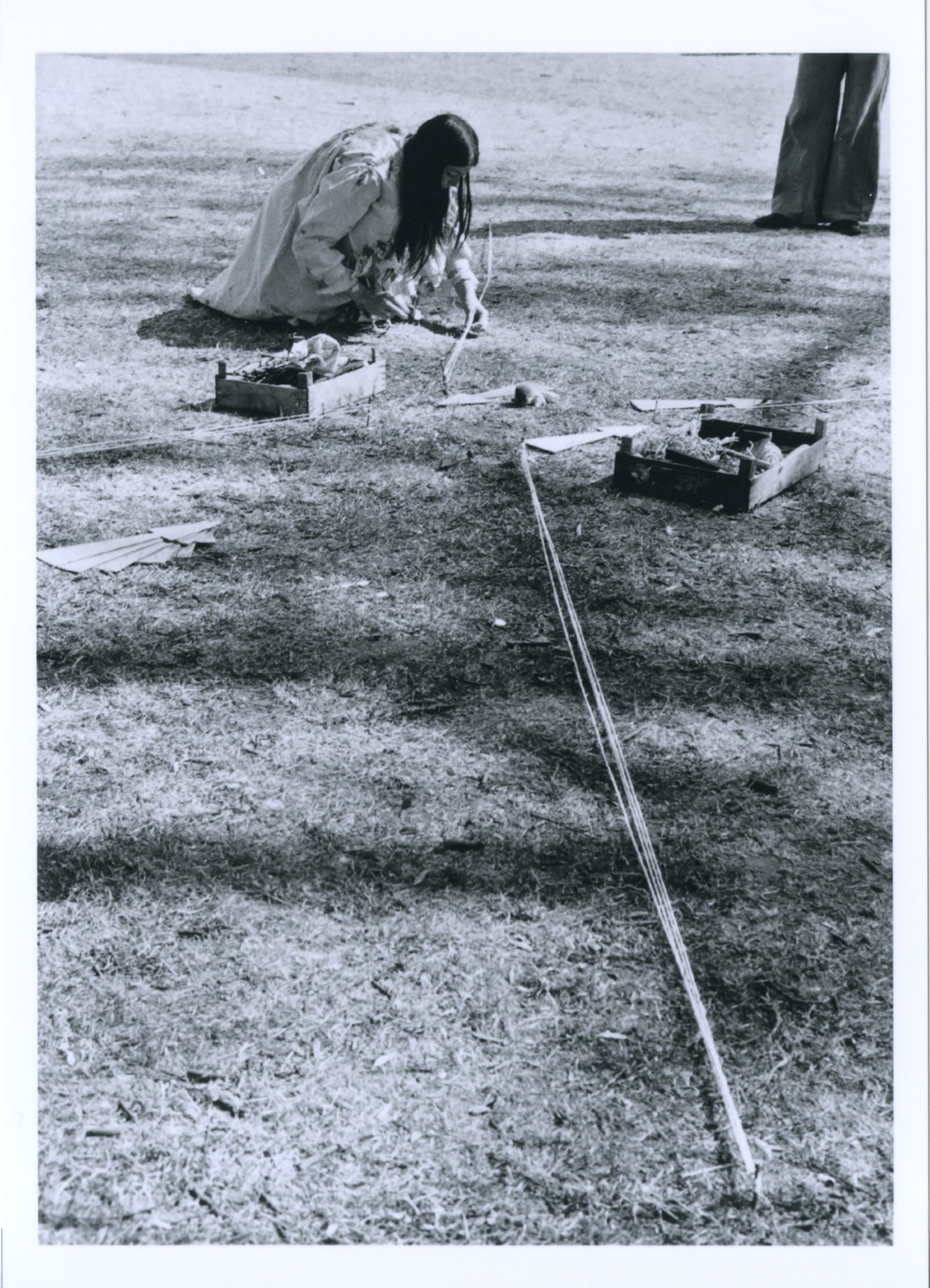

This week, her work goes on display as part of an exhibition in Paris entitled A Study in Scarlet, presenting past pieces by Tutti in the broader context of the movements and ideas surrounding her work – a sprawling conglomerate taking in Fluxus, the Beat Generation, American artist and composer Monte Cazazza, self-representation, formation of identities, sex positivity and more. Documentation photography of her previous actions is curated by Gallien Déjean alongside works by artists including Lynda Benglis, Karen Finley, Brion Gysin, Meret Oppenheim and Amalia Ulman. Looking back on her works in such a context has been an interesting process for Tutti: “There are moments when I’m looking at something and I see the connection with an event that had happened at the time, when I had no idea what was going to happen in the future, but it completely falls into place with what my life was going to present to me. Those moments make me feel quite good about what I’ve been doing, that it’s the right thing for me to do.”

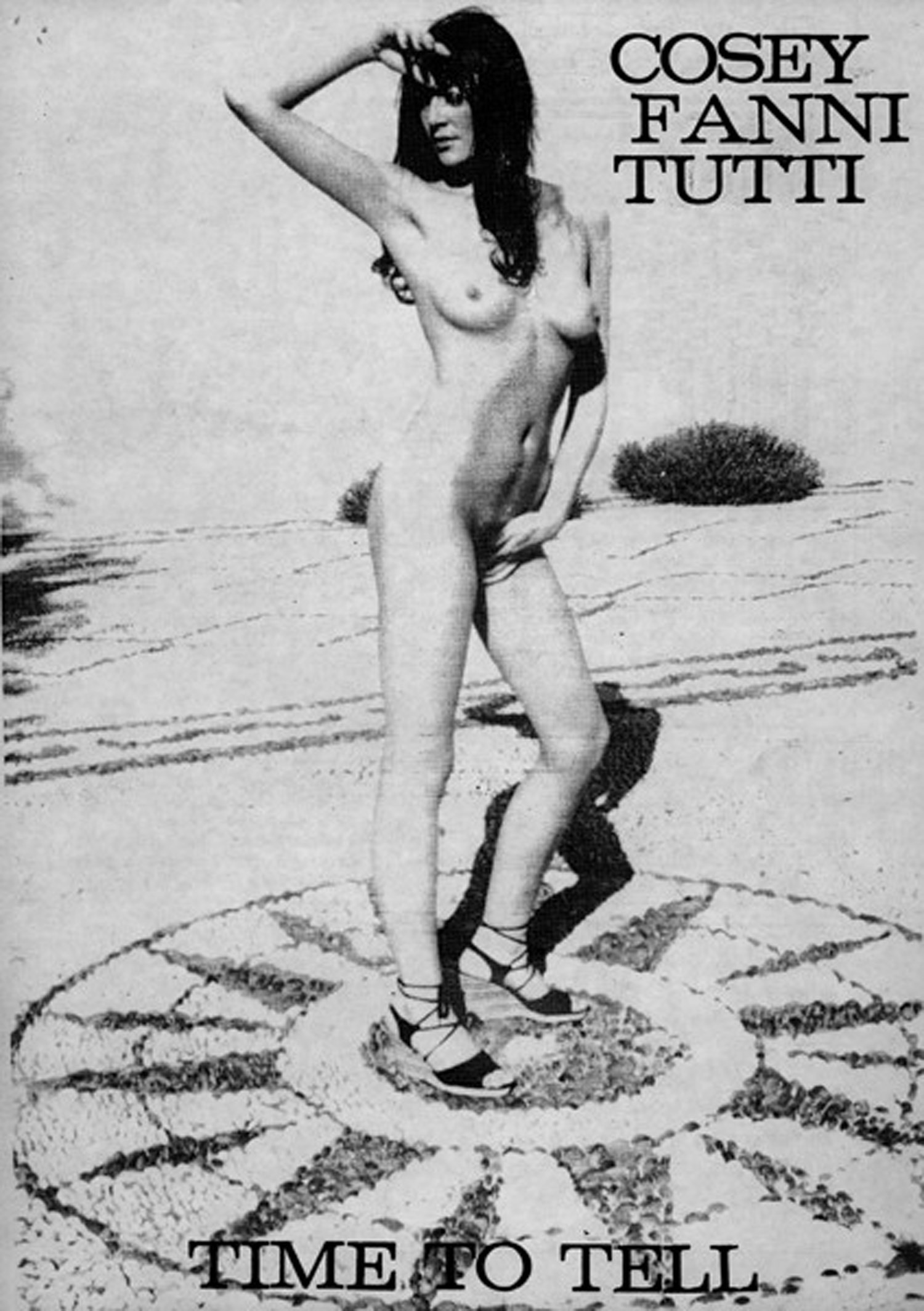

The show takes its title from a compilation some of the artist’s actions that was released on VHS in 1986; with ‘Scarlet’ a reference to her pseudonym when working as a stripper. “I didn’t want to be going out as Cosey, because for a start the name Cosey didn’t suit what I was going to be doing,” she says. “Scarlet was much more representative, like the Scarlet Woman, and even the suggestion of the colour red. It was very sexual for me, so that seemed more appropriate.” Yet where many artists adopt other personae for art-making, Scarlet was a more practical being – very few strippers work with their real name – and performatively, she has always been Cosey. In conversation as much as in her actions, she’s honest, forthright and open: her work is, as it always has been, a rallying call against suppression; a strident underscoring of the importance of being true to oneself, and being heard.

As a woman who espoused “sex positivity” before such a phrase was common parlance, that’s not been a straightforward path: in the 70s, discussions of female pleasure, the possibilities of the female body, sex work as art practice and so on were naturally far more radical than they are today. “I didn’t think of it at the time, I was just doing what I wanted to do and the judgment of others didn’t really bother me, because I wasn’t doing anything that would harm anyone,” says Tutti. “It was just me navigating the world in my own right as a human being. I think the problem now is that sex positivity is great, but you’ve also got the other side of the coin when people come in and hammer you down as much as they can. You have to be strong, as we each have our right to be who we want to be.” So how does she think a show like Prostitution would be viewed now? “Much in the same terms it was in the 70s, as sort of betraying feminism,” she says. “It’s still around now – women that work in porn are still seen as undermining women – you’re still going to come to criticism, as we still have people who are very moralistic. But at the same time they have no qualms about really laying into people and making their lives a misery. I think that’s far worse as a personal attack than someone just living their life and feeling free and exploring their sexuality.”

“I didn’t think of [being radical] at the time, I was just doing what I wanted to do and the judgment of others didn’t really bother me, because I wasn’t doing anything that would harm anyone” – Cosey Fanni Tutti

Bar piano lessons as a child – even then, she was more interested in deconstructing the possibilities of the instrument, rather than the more pedestrian exercises of practising scales – Tutti has no classical training, and never attended art school. Her practice instead has been one of relentless experimentation and intuition; and a dogged manifestation of her statement that “my art is my life, my life is my art”.

Her work is forged from such limitations, ameliorated by interpersonal and collaborative relationships, and born of improvisation over strict methodology. She sees that lack of training as wholly positive, enabling her to express how she lives and works “in my own way without any reference to other people – how they did it, what materials they had to use, and how to use them”. To paraphrase a statement she made in the 1980s: creativity begins with ourselves.

So what does she hope people today get from her work? “I just hope they find some connection with what I’m doing and some validation for what they want to be,” she says. “As long as what I do has inspired people to be who they are, then I can handle that, that’s good. If they can take it in their own direction and be themselves, that would be wonderful.”

A Study in Scarlet runs from May 17 until July 22, 2018, at Le Plateau, Paris.