It’s 20 years to the day since Sex and the City debuted on American cable channel HBO, a strange televisual anomaly starring Sarah Jessica Parker as a single 30-something woman making her way in New York City. It received uneven reviews, but also a second series. There was a reaction. It was the start of, pardon the pun, something big. The ensuing two decades, a lacklustre movie and its godawful sequel, have done nothing to dull its impact. In a manner only rivalled by Dynasty in the 80s, Sex and the City became a television show that not only reflected reality but shifted and shaped culture – specifically fashion. And ironically, for a series where the ever-fluctuating vagaries of the latter was placed centre stage, the clothes haven’t aged a bit, unlike Bradshaw’s aversion to mobile telephones, or her luddite distrust of the internet. Or indeed, unlike Dynasty, which is trapped in a time warp of an era it helped to create. The clothes in Sex and the City, by contrast, broke free of fashion and began to say something about style.

Dynasty is a fitting comparison. Like Joan Collins and Alexis Morell Carrington Dexter Rowan Colby, Sarah Jessica Parker and Carrie Bradshaw will forever be entwined. It’s tricky to see where the character ends and the actress begins – when Parker ascend the steps of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute gala in an outré outfit, we see Carrie going a little too far. (And perhaps wearing an entire bird on her head for her abortive wedding.)

“For many women now, when they think of Dior, they think of Sex and the City” – Maria Grazia Chiuri, Dior

And like Dynasty, the clothes drew much focus. Under the watchful magpie eye of Patricia Field, the stylist responsible for the series’ costumes, Carrie became a walking fashion plate. Her fantasy outfits sparked real-life trends, much akin to Hollywood films of the 1930s flexing more might than Paris couture when it came to silhouette shifts – or indeed, to Dynasty’s popularisation of the rampant shoulder pad. Around 2000, there was a run on vast corsages, which Sarah Jessica Parker sported when debating indulging a politician’s urolagnia in season three (that, in itself, feels not only relevant but prescient). When the fictional Bradshaw clutched a Fendi Baguette, it was reflecting fashion. The bag was already a hit. But her sporting of Dior’s neat, pochette-style Saddle bag in that same season – in seemingly endless permutations of colour and fabric – helped propelled it to cult status. “For many women now, when they think of Dior, they think of Sex and the City,” said Maria Grazia Chiuri of her first Dior collection. She remembered Bradshaw wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with “J’adore Dior”, and revived the look. She’s also just pulled the Saddle bag out of mothballs. She’s evidently a fan.

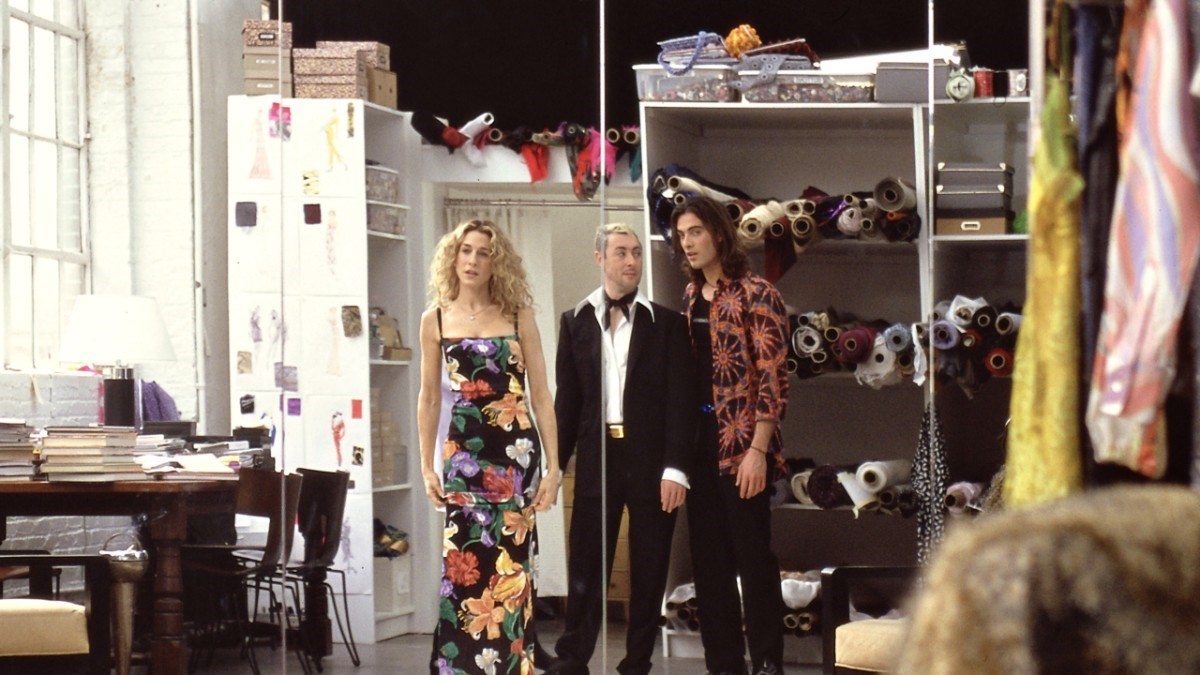

She should be – Chiuri has built her Dior around notions of female liberation and empowerment not despite, but through, fashion. That was something Sex and the City championed throughout its run (and why the two films, for many, left a bitter taste in the mouth). True, Bradshaw wore vertiginous, highly impractical shoes. But she purchased them herself, chose the style, and rarely did they impede her life. When that aforementioned politico dubs her latest purchases from Jimmy Choo “sexy” (Where There’s Smoke, season three, episode one), Bradshaw rolls her eyes. It’s not about being sexy for him, it’s about getting what she wants. Rarely, indeed, do the fashion items the female characters wear register with their male counterparts – they don’t dress to impress men, rather each other. When Samantha hauls out a gold leather fake Fendi filled with condoms (Sex and Another City, season three, episode 14) it’s to impress “the girls”, not a guy. When Bradshaw walks in a fashion show (The Real Me, season four, episode two), the audience is filled with a gaggle of cheering women; the man she’s dating, a fictional photographer named Paul Denai, watches as she falls, taking her picture, revelling in her discomfort. He doesn’t help her back up – the reaction of the women does.

“Rarely do the fashion items the female characters wear register with their male counterparts – they don’t dress to impress men, rather each other” – Alexander Fury

It easy to load Sex and the City with heavyweight feminist readings, and equally easy to rip those readings to shreds. The series is based on a book by a woman, Candace Bushnell, but created by a man, Darren Star – not that a female writer would necessarily make the series feminist by default, but certainly some of the attitudes and representations would have more reality. By the end of the final series, there is a certain two-dimensionality to many of the characters, especially Carrie, whose love of fashion became a caricature of obsession. Nevertheless, the series remains a rare example of a show whose main protagonists are all women, and whose relationships with each other, rather than with men, form the lynchpin of the plot line.

It has been hypothesised that New York is the fifth character in the programme; I’d argue, in actual fact, it’s the clothes. New York is a good-looking, incredibly famous cameo, a recurring guest who occasionally intrudes into the action. Fashion is there, in every episode, and always has something to say. Even in the earlier seasons, before SATC became abbreviated as such and hurrahed as a cultural touchstone, fashion was used to tell significant parts of a story, to propel episodes forwards. Consider the ‘naked dress’, a nude slip Bradshaw wears in the first season (Secret Sex, episode six) which the acerbic Miranda dubs “tits on toast”. The dress becomes the pivotal plot line as to whether or not it can be used as a tool for seduction, if Bradshaw could wear it, she should wear it. It still looks modern today – and, in a strange way, presages the nude-spangled awards ceremony dresses sported by the likes of Beyoncé and Jennifer Lopez. These women recognise their own bodies as part of their brands – something they own, and can leverage. Those dresses speak of confidence, not submission, just as Bradshaw’s represents sexual empowerment, and her urge to control her own destiny rather than surrendering it to a man’s wishes. She’s controlling her own narrative – through fashion.