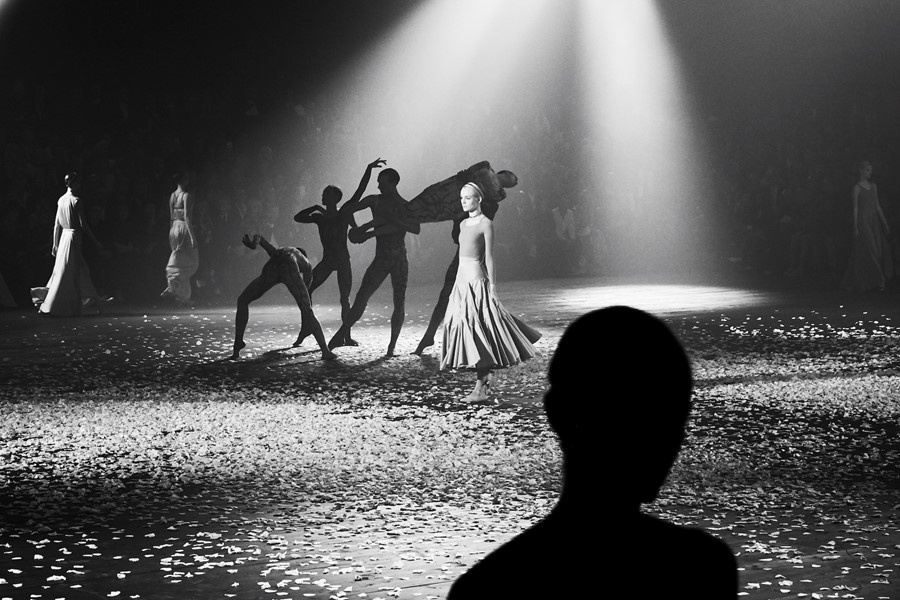

The house of Christian Dior has a long tradition in dance, Alexander Fury writes – and one which manifests elegantly and effortlessly in Maria Grazia Chiuri’s S/S19 collection

Maria Grazia Chiuri dedicated her Spring/Summer 2019 Christian Dior collection to contemporary dance in all its forms. That finds an automatic synergy with the aesthetic of Dior – the small torso, full skirts falling to mid-calf, the layers of petticoats and tulle all displayed a balletic grace. And Dior’s H line of 1954, with its dropped waist, minimised bust and gentle skirts, was a shift away from the pneumatic figure of the New Look to something akin to a dancer’s body.

Dior himself also actually designed costumes for ballets, although he recalled that even the craftsmanship of haute couture could not withstand the frenetic energy of dancers’ bodies, and his first endeavours fell apart after the first performance. “I have horrifying memories of a ballet called Thirteen Women which I designed at the request of Boris Kochno and Christian Bérard,” Dior wrote in his autobiography. “We ended by sewing the costumes on to the backs of the dancers, when they were already in position to dance across the stage.”

Maria Grazia Chiuri’s love of dance wasn’t so much about the clothes themselves – although her models, in their gently swathed layers of nude jersey with ribbon-bound heads and feet had the distinct look of an off-duty corps – but the movement of the body, the liberation of contemporary dance, and the reflection of female progression and emancipation through its practise.

To wit, Chiuri cited a female quintet of contemporary dance practitioners as formative inspiration behind this show: Loïe Fuller, Isadora Duncan, Ruth St. Denis, Martha Graham, Pina Bausch. None of whom conform to the tutu and pointe shoe school of dance, but rather to it as an ultimate freedom of expression – an inspiring proposition, for any designer.

Loïe Fuller

Born in Chicago under the name Marie Louise, Loïe Fuller began choreographing in burlesque, vaudeville and circus shows, developing her own natural movement and improvisation techniques. By the early 1890s, she had begun to combine choreography with silk, creating her signature ‘Serpentine’ dance. In part a reaction against classic ballet, it echoed both traditional folk dance and popular dances like the can-can. Fuller’s dance was combined with coloured lighting and theatrical elements, including luminescent costumes, to create a new, then-modern spectacle for audiences, engineered through the free movement of both body and fabric.

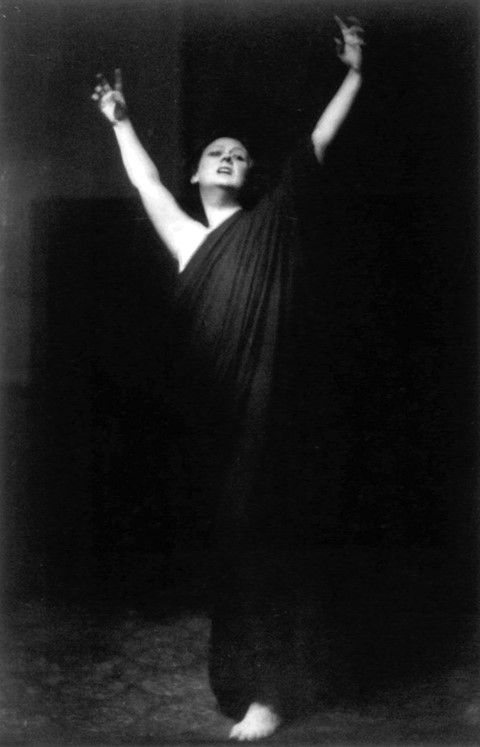

Isadora Duncan

Infamously murdered by her own hand-painted silk scarf – which tangled in the axle of an automobile she was a passenger in, and broke her neck – Isadora Duncan was celebrated as a pioneering force in early 20th-century dance. It was after moving to London in 1898, Duncan began performing in the homes of wealthy patrons, in poses and dress inspired by Greek vases and bas-reliefs in the British Museum. In 1902, she toured with Loïe Fuller across Europe, creating new works that emphasised natural movement instead of rigid formality of ballet, drawing inspiration from ancient arts, social dances, nature and the new American athleticism. Her costume underscored those ideas – a white tunic and bare feet, revolutionary in dance of the time. She described her work as “seeking that dance which might be the divine expression of the human spirit through the medium of the body's movement”.

Ruth St. Denis

Raised on a small farm in New Jersey and touring as a dancer, it was in 1904 that a then-25 year old Ruth St. Denis’ life changed. At a drugstore in Buffalo she saw an advertisement for Egyptian Deities cigarettes – it showed Isis, the Egyptian goddess, enthroned in a temple. It captivated St. Denis, who was inspired to investigate Asian dance and ancient mysticism, and devise new, modern dances that expressed those themes and philosophies. The debut of this approach was her 1906 piece Radha; inspired by Hindu mythology, Radha is the story of Krishna and his love for a mortal maid. Although neither culturally accurate nor authentic, Denis’ dance chimed with a rage for exoticism often dubbed ‘Japonisme’ that inspired culture at large (including the Ballets Russes, and the work of the couturier Paul Poiret). To St. Denis herself, dance was a spiritual expression, reflected through her choreography. Together with her husband Ted Shawn, St. Denis founded The Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts in 1915 – the “cradle of American modern dance”. One of her more famous pupils was Martha Graham.

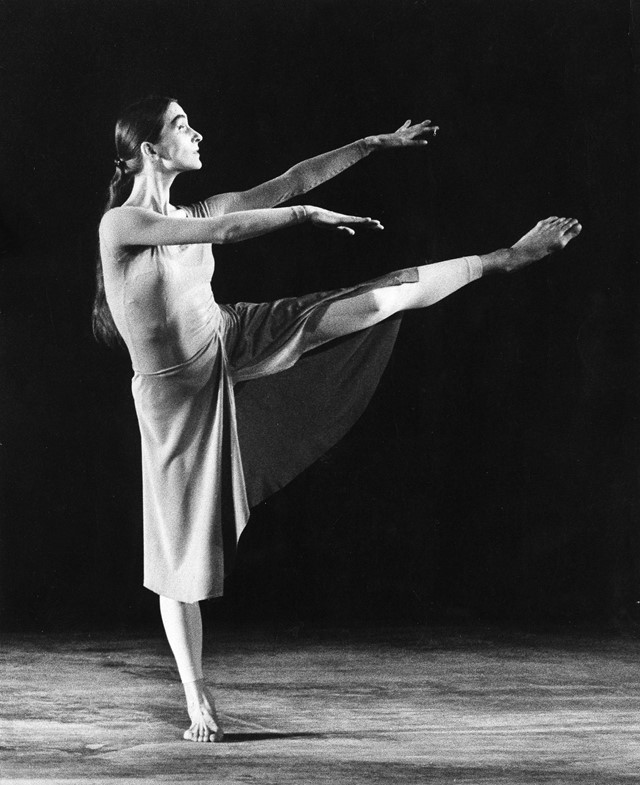

Martha Graham

Dubbed the “Picasso of Dance” for her significance and continuing influence, Martha Graham arguably brought dance into the 20th century. Her dance methodology, the Graham technique – of whirls and spirals, falls and rises – has been called the “cornerstone” of American modern dance, and was a rejection of both ballet tradition and the first generation of modern dance. The Martha Graham Dance Company is the oldest in America, founded in 1926 when Graham was 32, and still expounding her teachings today. Having begun dancing as a teenager, Graham debuted her first independent concert in the year it was founded, consisting of 18 short performances choreographed by her. In 1929, she created Heretic – dominated by sharp, constricted motions and with dancers simply clothed, it offered an insight into her future work and distinct style, often revolving around ideas of Americana and Greek mythology. The idea of the power of the feminine was vital – she extorted her dancers to “move from the vagina” – indeed, Graham's method has been seen as reclaiming the female body as an artistic medium.

Pina Bausch

The German Pina Bausch was a leading influence in the field of modern dance from the 1970s until today, with work influenced by and reflecting German Expressionism. "I loved to dance because I was scared to speak,” Bausch once said. “When I was moving, I could feel.” As a child, Bausch would amuse customers in her parents’ restaurant in Solingen, Germany with impromptu dances. After studying at the Juilliard School, where she performed with modern American dance groups and the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, Bausch returned to Germany in 1962 and began choreographing five years later. When she became director of the Wuppertal Opera Ballet in 1973, she began to explore her own style of Tanztheater, combining dance with other performance disciplines, and expressing emotion and psychology through performance. Her approach garnered a cult following. She was credited with reinventing dance – or at the very least transforming its landscape. “I am less interested in how people move than in what moves them,” Bausch once said.