Taken from the A/W17 issue of Another Man:

It’s often said that every collection begins with an obsession. Miles Chapman would beg to differ. He insists his life was never consumed by the time and effort involved in accumulating the thousands of photographs, 3D slides, drawings, paintings, magazines and ephemera that make up his collection of mid-20th-century male erotica. But this is still a story of obsession – if not the collector’s, then at least the collected.

When he first started buying photographs in New York 30 years ago, Chapman felt he was helping to save from obscurity – or, worse, destruction – huge bodies of work that documented the vibrant gay culture that flourished under the surface of America’s post-war boom. “I never imagined I’d do anything with it,” he says now. “I just wanted to preserve it.” But time passing has given Chapman’s massive collection a significant heft. An historical significance, almost. Look at it now and you can’t miss the seeds of Mapplethorpe, Weber, Ritts, the mythologists of modern masculinity. When underground went overground, it changed the way the world looked at men.

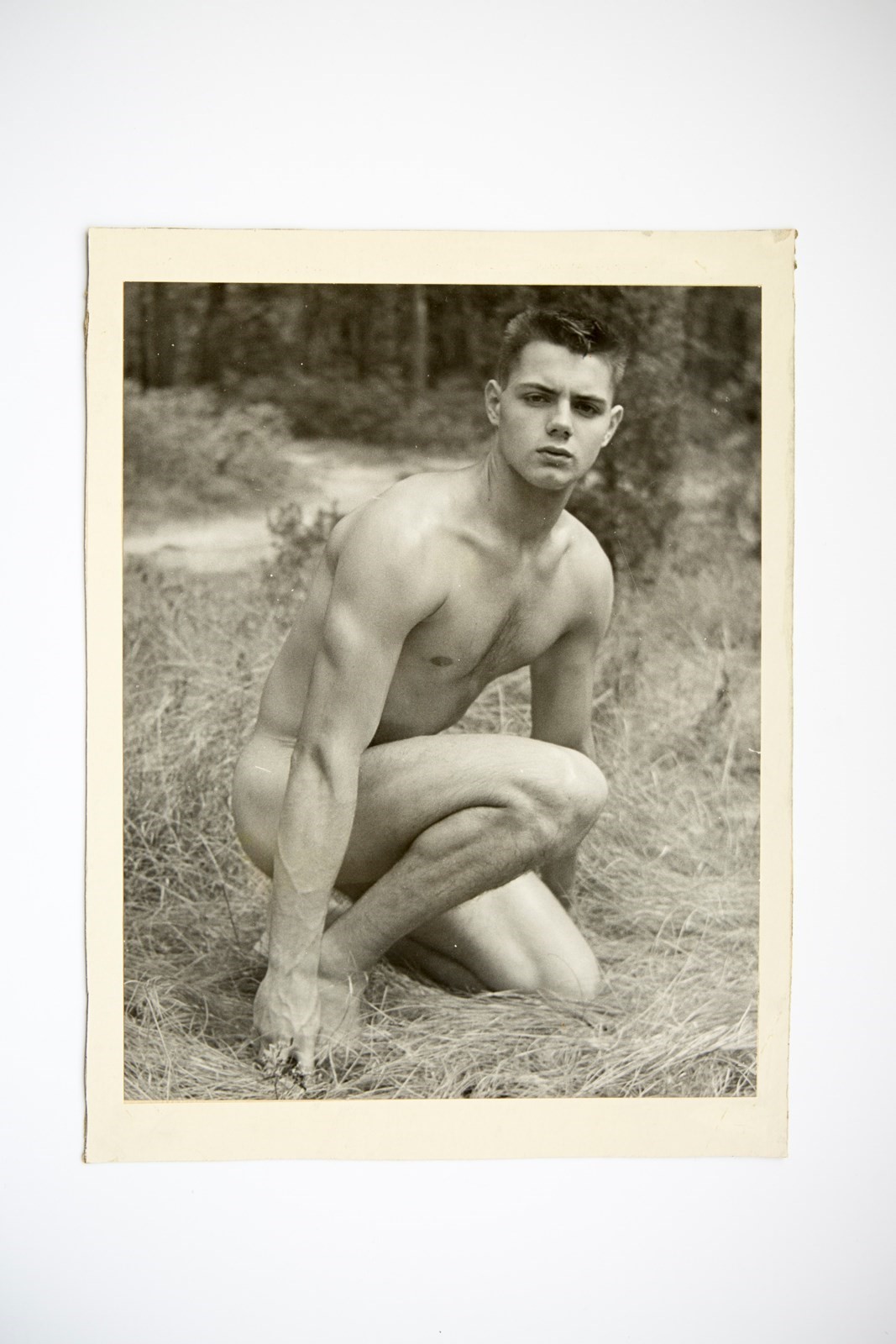

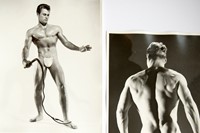

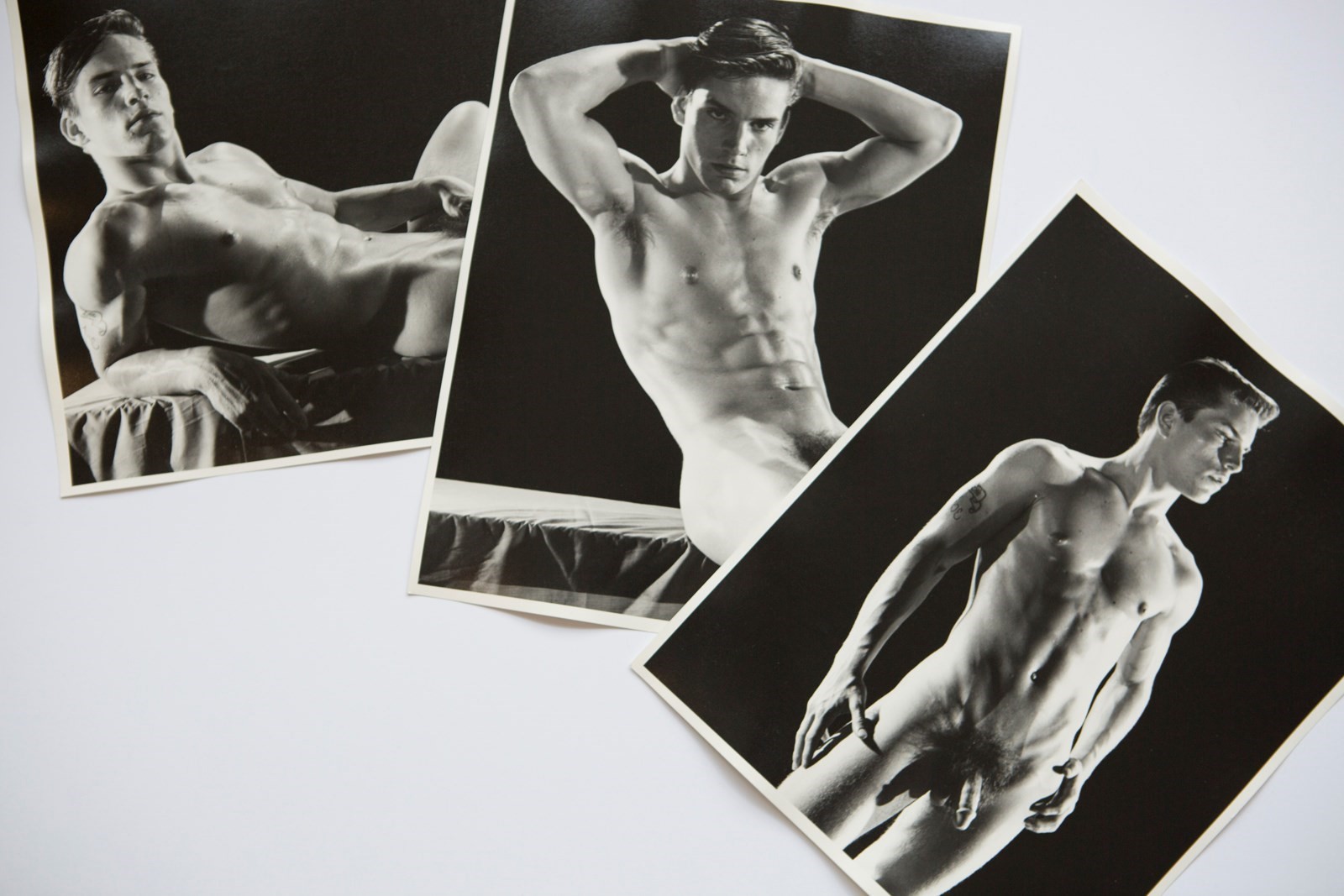

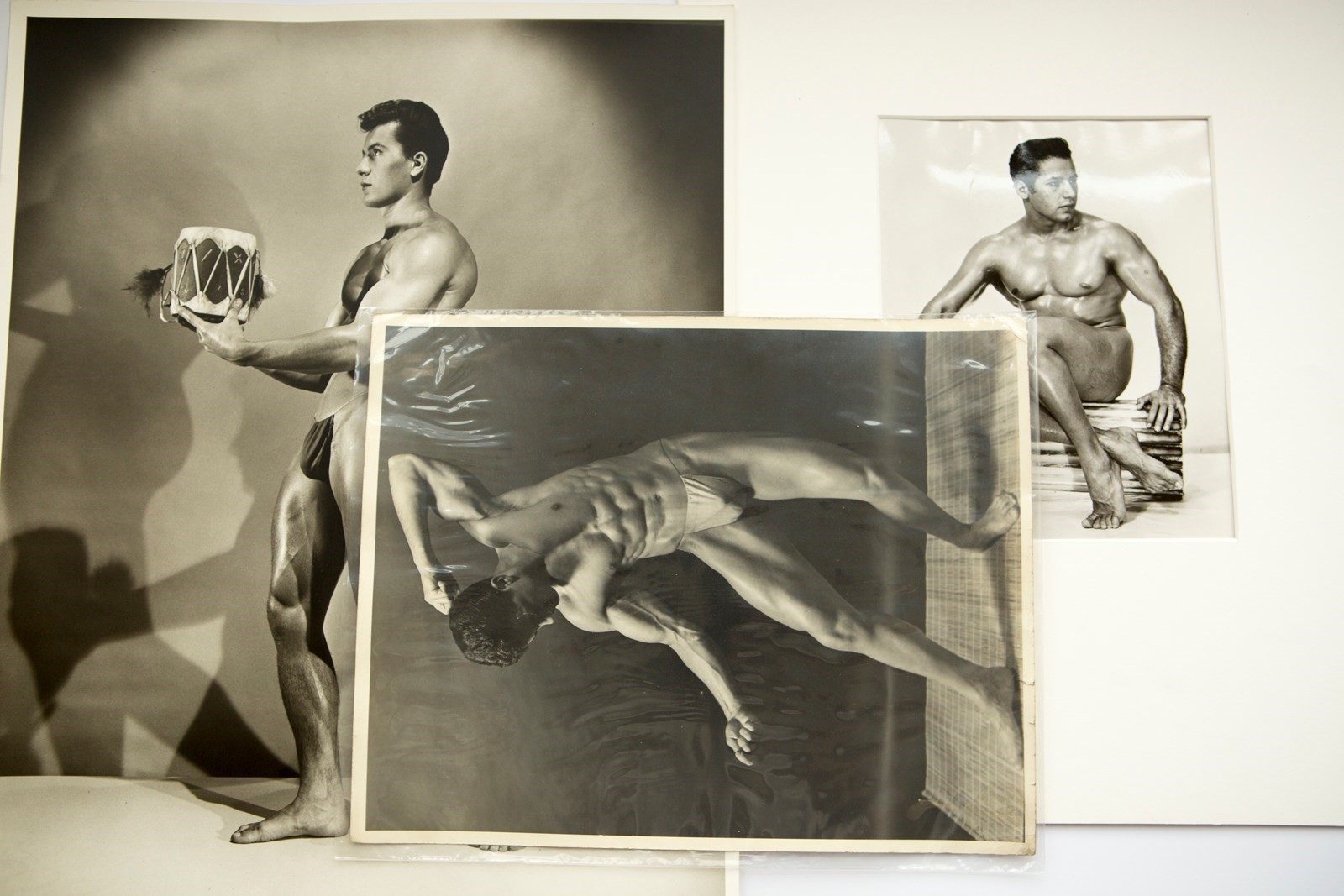

But that’s not what was on Chapman’s mind when he was making his regular Sunday-afternoon, post-brunch sallies to Physique Memorabilia on East 12th Street. It was a walk-up apartment in a townhouse (complete with squawking parrot), piled high with boxes full of photographs of young men posed as bodybuilders, wrestlers, cowboys, young Greek gods. Pin-ups, essentially. These images were the work of a handful of “studios” across the country, familiar to a gay cognoscenti who could debate the relative merits of Bob Mizer’s Athletic Model Guild, or Don Whitman’s Western Photography Guild, or Alonzo ‘Lon of New York’ Hanagan, Dave Martin of San Francisco, Kris of Chicago, Douglas of Detroit or Bruce of LA.

In their celebration of what was discreetly labelled “the undraped male form”, these men waged a running battle with the law. Several of them served prison terms. Lon went to jail. So did Mizer, for “the unlawful distribution of obscene material through the US mail”. To 21st-century eyes, the charge of obscenity is positively quaint, but in the Eisenhower era, the smallest whiff of male concupiscence could give the bluenose morality squad an attack of the vapours. It was sublimated in Hollywood heartthrobs like Tony Curtis, or a mainstream muscle-movie star like Steve Reeves, who, early in his career, posed for Spartan of Hollywood. Such work was, to all intents and purposes, the male equivalent of the casting couch that shadowed the careers of female movie stars, which would explain why some of the major male movie stars of the era showed up in physique photography before they were famous.

Chapman doesn’t use the term “male erotica”. He thinks it sounds like porn. What impelled him to spend hours rifling through the boxes at Physique Memorabilia and, later, Gay Treasures on Hudson Street, was the prelapsarian innocence of the images: young men cheerfully giving their best while posing in modesty pouches, almost chaste compared to the borderline hardcore spreads in gay magazines such as Drummer, Honcho and Mandate that crowded Manhattan newsstands in the 70s and 80s. “You’re always nostalgic for things you just missed,” Chapman muses. “And this was a world that was slipping away.” When Tina Brown moved him to New York in March 1984 to be her lieutenant at Vanity Fair (a role he’d served for her at Tatler), AIDS was decimating the gay community. “Next-of-kin wasn’t your gay friends, it was your mother, your sister, your uptight brother-in-law in Peoria,” he recalls. There were endless stories of relatives who would strip an apartment and dispose of its contents in shame. With their orphaned collections of photos and magazines, places like Physique Memorabilia became repositories of lives lost. The value of the material could be calculated in its pricing: $2.50 for a print, $5 for an 8x10. “But it felt important,” says Chapman. “It needed someone to look after it and save it.”

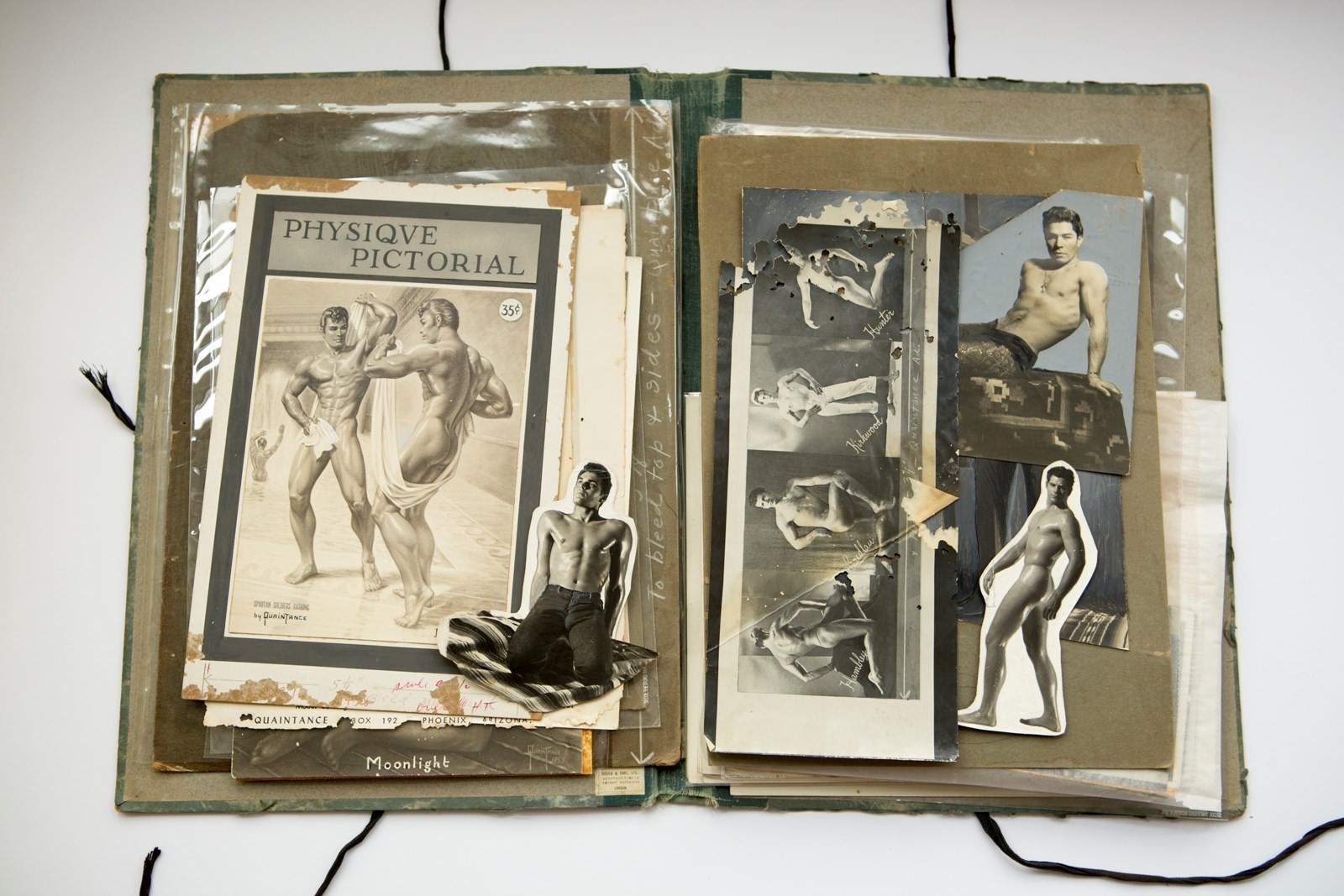

By the time he moved back to London in 1990, his collection of photographs numbered in the hundreds. His journalist’s instincts had kicked in, piquing his interest in the mavericks and unique characters who made the work in the first place. Bob Mizer, in particular, captured Chapman’s imagination. He had started out as an assistant for Fred Kovert, a silent-screen actor who’d relaunched himself as a physique photographer in the 40s, but Mizer rapidly supplanted his mentor. He called his studio Athletic Model Guild, so he could say his semi-naked boys were life models to inspire amateur artists. Clients ordered AMG’s photos by mail (shipped “under plain wrapper”) from Mizer’s magazine Physique Pictorial. “It was underground,” Chapman says. “Remember, homosexuality was still the love that dare not speak its name.”

Physique Pictorial was a proto-zine, the best of the many little magazines that the studios that followed AMG produced to advertise their wares. It was based in the boarding house of Mizer’s mother Delia, at 1834 West 11th, in downtown LA. As the business expanded, Mizer bought all the houses on the block until eventually he had a compound. It was scruffy, but there was a pool in the middle, and the sloping roof on one of the houses had been painted to look like a mountain range, so when a boy got up there with AMG’s pet goat, Mizer could create a horny little riff on Hansel & Hansel. Delia sewed the posing pouches.

As Chapman tells it, Mizer’s models were originally soldiers, sailors, a floating population of similar itinerants, and young men who’d gone West. “Later, it turned into street hustlers, pure and simple,” he says. They’d come knocking on the door on W. 11th because they could be sure of a place to stay. And, for those in the know, Physique Pictorial had a seamy subtext. Mizer had a private code, similar to astrological symbols, which insinuated the availability and the special attributes of some of the models on offer; the thinly veiled innuendo of their personality traits. “Early riser”?

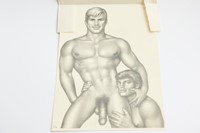

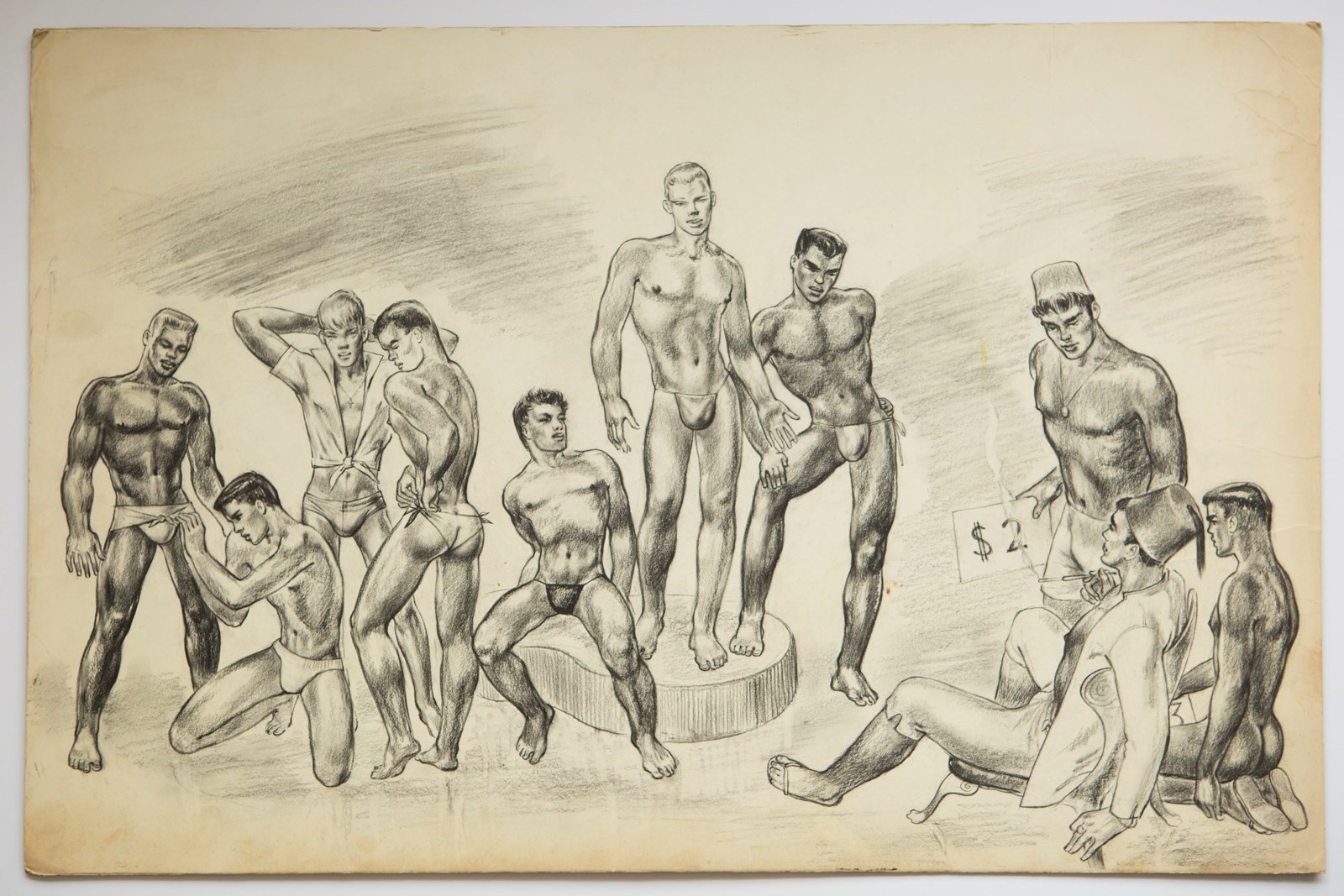

When Mizer died in 1992, Chapman learned that he’d left his estate to Wayne Stanley, the former lawyer who’d worked as his model wrangler. He wrote to him, established that he was interested in selling, and eventually visited Stanley for two week-long furloughs in Alameda, on the San Francisco Bay. Each day, Chapman would sift through boxes of material, show Stanley what he’d chosen at the end of the day, and then a price would be named, usually a few thousand dollars. This was the gold mine. Chapman acquired the full print run of Physique Pictorial from 1951 to 1990 (including three of the eight known existing copies missing from Taschen’s “complete” 1997 reprint) along with thousands of photographs. He also bought the originals of the paintings and drawings that graced the zine, by Tom of Finland, Harry Bush, Quaintance, Etienne, Spartacus – the Michelangelos and Raphaels of mid-century gay art. Plus, ephemera imbued with the curious allure of arch-fetish objects, from the contents of Mizer’s wallet (he carried his hall pass from John H. Francis Polytechnic High School well into adulthood) to one of Delia’s hand-strung posing pouches, in the same strange shade of burnt orange that, early on, was painted over the genitalia of naked models for the mail order business. (The paint was easily wiped off the photo when it reached its destination.)

Mizer was the mother lode, but Chapman went on adding to his collection, sometimes through eBay, or rewarding personal connections, such as face-to-face buying trips to Lon of New York and Dave Martin of San Francisco. Bruce of LA had left his estate to one of his boys, Scotty Cunningham, who sold it to Kent Schlesselman, from whom Chapman acquired some extraordinary photos of ‘Little Joe’ Dallesandro from the early 60s, long before he found fame as a Warhol superstar. His erection looks confrontational. (Bruce paid his models more for hard-ons.)

“These images are intense because they’re imbued with secrecy and taboos,” says Chapman, “but they’re also from an era before JFK’s assassination, before Vietnam, so they’re innocent too.” It wasn’t only an American phenomenon – Chapman can name equivalents for Mizer and Bruce in the UK and France and South Africa – but the body culture it celebrated does feel distinctly American. “Yes, there’s an element of triumphalism,” Chapman agrees. “They felt they won WWII by being bigger and better.” It was also the war that opened up sexuality, especially for men, like never before, in the process creating a new and much wider audience for the specialised output of studios like AMG and Western Photography Guild. They recreated archetypal heroic images of masculinity, youth and sex that have a timeless resonance. “But they had to have an audience,” Chapman adds. “They had to be expressing it to someone.”

Hero worship – that’s how cults are created, how myths are born. Chapman’s story illustrates how a collector can help shape a mythology. He doesn’t collect anymore; diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 2002, his energy has been directed to more pressing concerns and he’s currently looking for a custodian for the collection. He lives in West London with his partner of 35 years, in a house whose remarkable interior is testament to a life lived in the fullest appreciation of the world’s curiosities, eccentricities and wayward beauties. Does Chapman feel his collection is complete? “Never,” he sighs. “There’s still so much out there. You never know what’s going to turn up. Imagine unearthing a full set of Bruce of LA’s ‘Little Joe’ photos, hand-printed, in a huge format…” So we sit for a while in a comfortable silence, imagining.