The publication of Priya Ahluwalia’s first book, Sweet Lassi, created to coincide with her final collection as part of the University of Westminster’s Fashion MA, heralded the London-based designer as one of fashion’s most essential emerging voices. Capturing the mountains of waste clothing in Panipat, India, the fabric recycling capital of the world, it served as a wake-up call to the fashion industry about its shocking excess – her own label Ahluwalia primarily uses vintage, deadstock and recyled fabrics – and continues to ignite conversation two years on. “I still get asked about that book to this day,” she tells AnOther.

Her latest book, Jalebi – named for another Indian confection – and accompanying digital exhibition seeks to further expand Ahluwalia’s voice outside of the clothing she makes, providing a loving portrait of the district of Southall in west London, the largest Punjabi community outside of India. It is an area Ahluwalia frequented often as a child growing up in London – the designer is of Indian and Nigerian descent – and one which she says could not exist anywhere else in the world. “I wanted to show how beautiful of a place it is,” she tells AnOther of how Jalebi began, “and how interesting it is when different heritages mix together in a geographical location, and all the nuance that it brings with it.”

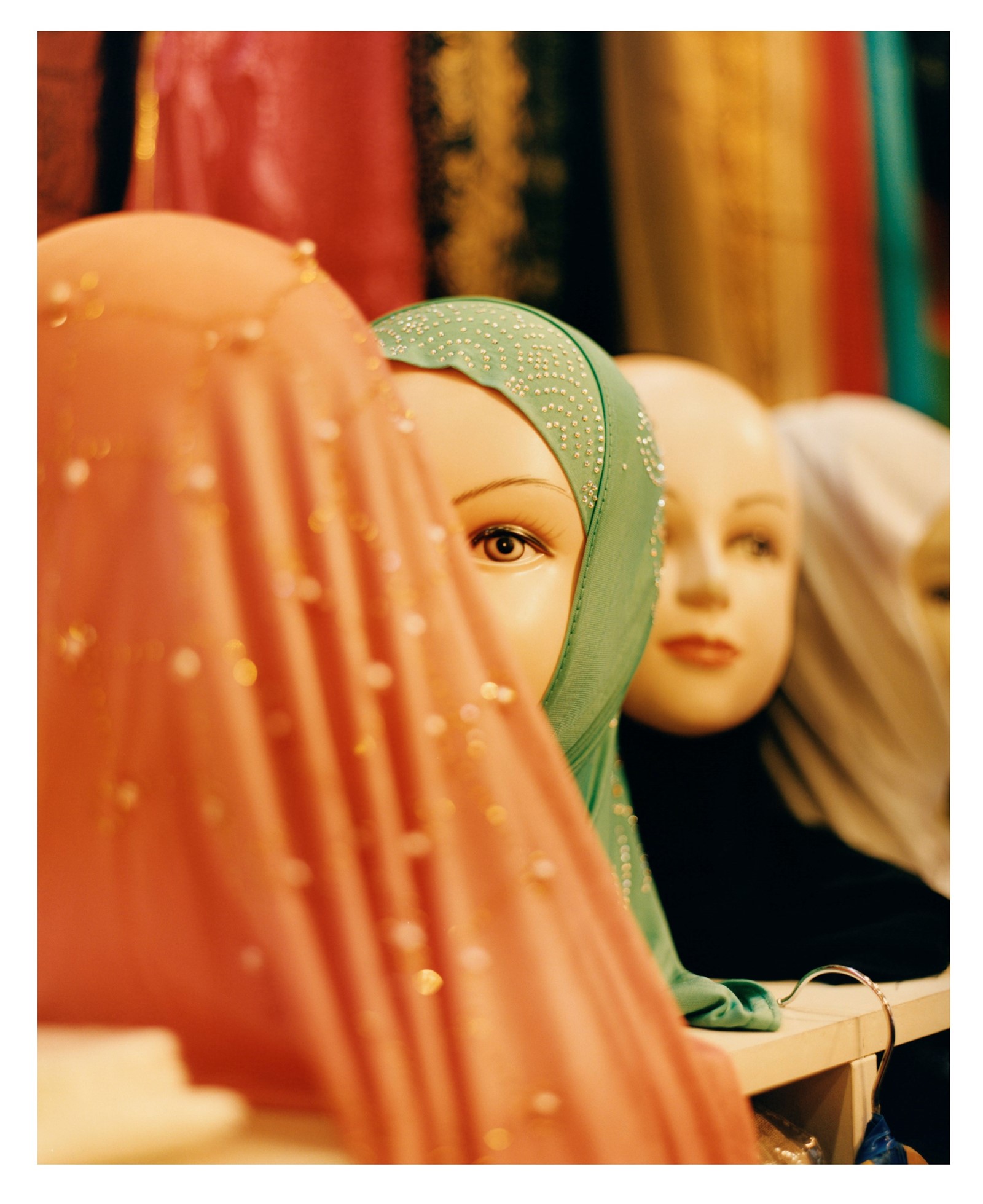

The book and exhibition centre on a series of images taken by photographer Laurence Ellis, a longtime collaborator of Ahluwalia’s, over a year of Southall’s community and residents. Existing somewhere between “the imagined and real”, as the blurb describes, they hover between documentary – the colourful, plastic-stacked shop fronts; families on the street, or in markets – and something more wistful, like a series of images of cars parked on Southhall’s surburban streets, draped with stitched-together silk scarves. In some, Ahluwalia’s clothing features, though that was never meant to be the focus: “some of the people in the book are wearing my clothes, because my clothes are inspired by people like them,” she says.

Alongside, a selection of existing photographs of Ahluwalia’s family, which have been a prescient inspiration since founding her label. “I sometimes think that looking towards your own personal history gives you something that no one else has got,” she says. “No one else has my family. No one else has the experiences my family has had. It just shines on it a different light to look at it from my perspective.” Her maternal ‘nana’ – with who she travels back to India often – is a particular focus of Jalebi, interviewed by Ahluwalia in the book and forming a number of sound clips in the digital exhibition. “We’re quite obsessed with each other,” she laughs.

The question of what it means to be mixed heritage in Britain today is at the heart of Jalebi, and though the book retains a celebratory air, Ahluwalia didn’t want to sugarcoat the difficult truth of living in immigrant communities (in a series of particularly prophetic images in the book, Ellis captures a protest to remember the death of anti-racism activist Blair Peach at the hands of police officers led by the Southall Black Sisters). “I love being mixed heritage, I’m Indian and Nigerian, and I’m also British. It’s made my life rich and difficult at the same time; lots of nice things have come from it and lots of hard things have come from it,” she says.

Here, coinciding with the exhibition’s launch, part of London Fashion Week’s first online edition, Ahluwalia speaks on Jalebi in her own words.

“Jalebi came from loads of things: I was going to Southall a lot on my own as I got older – before it would have always been with family – and I started looking at it through my own eyes. Not because my mum needs to buy something, or my nan needs to buy something. I thought about how I wanted to show how beautiful of a place it is, and how interesting it is when different heritages mix together in a geographical location and all the nuance that it brings with it.

“I had worked with Laurence [Ellis, photographer] and Riccardo [Maria Chiacchio, stylist] both in the past; I met Laurence properly when he did a shoot for my brand in More or Less magazine. In terms of Laurence’s work I think we resonate on a lot of levels because he works so much with highlighting communities that are underrepresented. I think he does it in a real way where he lets the subjects and the people speak. He does it in a way that’s educational. I can’t remember if we started with the intention to make a book, but it built and built over the last 18 months.

“I wanted to show how beautiful of a place [Southall] is, and how interesting it is when different heritages mix together in a geographical location and all the nuance that it brings with it” – Priya Ahluwalia

“We went to Southall maybe eight times. We went a lot over the year. For example, as we got towards the end of the book what I realised was missing was the actual geography of the place. So then we added in the images of the shop fronts, which are something I find so fascinating; the shop fronts are mental. We cast it with Troy Casting, who I’ve worked with a lot; he’s a really good friend of mine. We wanted to involve actual Punjabi families, and people that were part of this area. It was a real mix. One of the models is Nikhil [Rai] who I’ve worked with before. So here it’s with him and his mum and dad. While we were shooting we were talking about Southall and it would be like ‘oh, his aunty would live up the road’; it was really talking about community and how strange and unique that is.

“I always thought I wanted not to be a designer but a creative director; I love working on projects. It’s not just about making clothing. I really enjoyed the process of making Sweet Lassi and I definitely thought I want to do it again. I wanted this book to be about Southall, I didn’t want it to be an advert for Ahluwalia, I didn’t want it to be a lookbook. Some of the people in the book are wearing my clothes, because my clothes are inspired by people like them. It was important to show that the brand is about much more than selling clothes.

“As a designer, there are so many different ways you can tap into research, but I sometimes think that looking towards your own personal history gives you something that no one else has got. No one else has my family. No one else has the experiences my family has had. It just shines on it a different light to look at it from my perspective. When I looked through the pictures with the people in my family they did not think it was cool, or interesting – they were just like, ‘it’s us’. But I think it’s amazing. I look at this stuff because of how I grew up, who’s looked after me, what food I’ve eaten, what TV I’ve watched. All of that shaped me as a person.

“I’m really close to my nana, who I interviewed for Jalebi. We go on holiday to India together. We’re quite obsessed with each other. As I’ve got older I’ve realised that time does run out, I realised I didn’t know the answer to a lot of questions like, where did she live when she was a kid? What was the process of her getting married to my granddad? I wanted her opinion; I’m talking about her all the time so I really wanted to speak to her about it all. She was kind of nervous speaking to me, but I just said no one else will have this resource to look back on for years to come. It was very personal.

“I think that looking towards your own personal history gives you something that no one else has got. No one else has my family. No one else has the experiences my family has had” – Priya Ahluwalia

“It was important that the exhibition be accessible. I don’t want to do this big project about Southall and then do a jumper that says ‘Southall’ on it and it’s beaded and it costs £500. This work is for them as well. I really feel like through the imagery you can tell this book celebrates these people; it puts this story into the forefront. With this book, I want people to look outside of themselves, I want people to see how beautiful, and all the nuances, that immigiration and diversity can bring. But I want people to see that it can also be really difficult; in the book we have some images from a protest in Southall about Blair Peach, who was killed by the police.

“We’re told – and the interview with my nan highlights this – that England is this amazing place, which comes from having been colonised by England. When you have British forces in India saying Britain is better than you – or whatever, I can’t even repeat it because it makes me sick – then of course people are going to come and want to live there. But then we get there and we suffer. And it’s happened on all sides of my family. My dad is Nigerian, it’s happened on that side, my mum is Indian, it’s happened on that side, my stepdad is Jamaican, it’s happened on that side.

“So Jalebi is also about bringing feeling and emotion to this topic, to the idea of immigration. Because I think sometimes people can think of it statistically, but I think in this book it’s emotional. It’s making humans – and more than humans – out of these people. I’ve been working on this for 18 months. It’s not a reaction to something that’s happening in the news. This is what I live. This is what I go through, every day. The colour of my skin affects my life every single day. Before we’ve been told not to rock the boat. What might be different now is that I finally feel brave enough to say that to someone.”

Jalebi is available to purchase at ahluwaliastudio.com from today, with all sales of the book and photographic prints going to the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust and Southall Black Sisters.

The digital exhibition is available to view from 1.15pm today (June 12, 2020), at londonfashionweek.co.uk and ahluwaliastudio.com.