“I want young people struggling with their identity to feel less alone,” says Mohsin Zaidi of his new book, which charts his journey towards the reconciliation of his faith and queer identity

Much of the narrative on queer Asian and Muslim identity over the past few years has been hijacked by the Birmingham schools race row, reports of people being forced into heterosexual marriages or contending the burden of homophobia and Islamophobia in their respective communities.

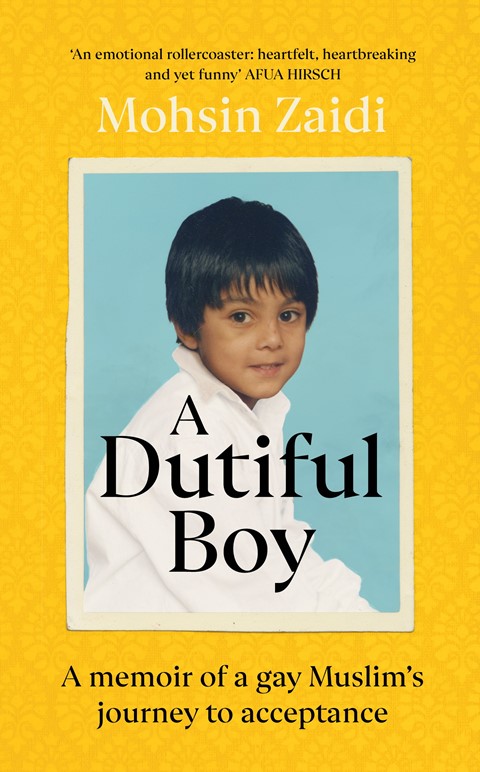

But queer Muslim identity doesn’t have to be centred on trauma. It’s this that’s the premise of criminal barrister and debut author Mohsin Zaidi’s emotionally searing memoir A Dutiful Boy: A Memoir of a Gay Muslim’s Journey to Acceptance. Charting coming of age in a queer conservative Muslim household in East London, we see Zaidi grapple with faith, family bonds, community expectations and class, ultimately reconciling both his faith and queer identity. Though Zaidi’s debut can make for challenging reading – from his father enlisting a ‘witch doctor’ in an attempt to ‘cure’ him to grappling with racism on dating apps – even so, A Dutiful Boy makes for a deeply moving and ultimately triumphant memoir.

With the book released later this week in the UK, I called Zaidi at his London home to find out what compelled him to write his memoir, revisiting his upbringing and what challenges queer Muslims still face today.

Salma Haidrani: Why did you decide now was the right time for readers to hear this story?

Mohsin Zaidi: It’s always important to hear stories that are different from the ones we’re used to. In a way, it feels like my life is starting now. I’ve had to deal with conflicting identities for so long and now I feel like I’m in a place where they can co-exist harmoniously. And so life is actually a little bit boring – in a good way – which meant it felt like the right time to write things down that I have carried for a long time. I don’t have to worry about obstacles or challenges in a way that I did when I was a kid. At the end of the book, I write, ‘this story is one set in the past. What matters is not this story, not my story, but the story of what happens next.’ I guess that’s how I feel.

SH: A Dutiful Boy celebrates how it’s possible to reconcile being Muslim, queer and South Asian rather than a clash of competing identities. How much did you set out to achieve this?

MZ: I’m not an expert on Islam and I’m not telling people how to practice their faith. I’ve grown into a place where I’m comfortable. If you asked me even two years ago, I wouldn’t have been. It’s the first time in my life I’ve felt whole. Unfortunately, it’s not as easy for everybody.

SH: Did you find writing your memoir therapeutic?

MZ: There were definitely moments where I was typing and crying at the same time, like when I was writing about how difficult it was to keep my sexuality a secret and how it meant I kept everyone at arm’s length, even people I really cared about. The first draft was definitely just for me, not for anybody else. That was the cathartic version. And then the edit was about making it accessible for people beyond me! Therapy is a very private thing to do. This is very public and this is not the entire story by any means.

SH: From conversations with your mother about your identity and love for your partner interspersed throughout the book, why was it important for you to imbue hope throughout the memoir?

MZ: The heroes of this story – if there are any – are my family. It was important for me to set a hopeful tone because the narrative around Muslims in this country can be very negative. We’re usually portrayed in stereotypes. I wanted people reading it to know that Muslims are just people and that we have our own struggles.

SH: There’s a lot of emphasis on family bonds. Often, we read about how queer people of colour or queer Muslims have to choose between their queer family, their faith or community but you showed how it’s possible to embrace all ...

MZ: Everybody’s journey is different. It’s still something a lot of people struggle with and I think it will be for a while. For me, the message is one of love. I found a way of loving my family and they found a way to love me in spite of the barriers between us. I think the message is to be kind to one another, give each other the benefit of the doubt and love each other. For me, getting my parents on board wasn’t a political agenda – it was about love.

SH: The book illuminates on not only race and sexuality but on class and social barriers – why was it important for you to focus on this?

MZ: I didn’t understand the class system until I went to Oxford and realised things like the fact that not everybody needed a loan to pay for university. Class is the biggest obstacle we face in a society. It’s a problem that’s getting worse because the gap between the rich and poor is getting wider. Unless we acknowledge this and do something to remedy it, the problem is going to persist. Gender, race and class are not separate from each other. If you’re an ethnic minority, you’re disproportionately likely to be poor. Women earn less than men in alike jobs and working class women have very particular issues that other women do not. For me, class permeates everything. The way we speak, what school we went to, what university we went to, even when it comes to our supermarkets!

SH: Where did the title come from?

MZ: There’s something in that word ‘dutiful’ that I thought was really important. The word ‘dutiful’ really invokes the idea of expectation, obligation and culture and wanting to do the right thing as well as a struggle to be somebody.

SH: What’s the response been like to your book so far?

MZ: It’s been extremely positive, overwhelmingly so. I’ve received the most wonderful and touching messages. Last month, the author Mark Haddon wrote about the book on Instagram and described it as “unputdownable”. Two days before that, Elizabeth Day posted about the book. It’s surreal as the book isn’t even out yet – it’s been postponed because of Covid-19 so I’ve had this strange lockdown where everything’s been turned upside down but every so often, these things happen online and I almost don’t know what to do with it!

SH: Your book has been touted as having the capacity to ‘save someone’s life’ – how does that feel?

MZ: A book like this might have helped me when I was younger. That’s one of the reasons I wrote it. If it does help save lives – or save even one life – it has done something really positive. But it’s difficult for me to engage with whether it will or not. I included a list of resources at the end of the book, in the hope that if readers are feeling isolated, they can know that they have somewhere to turn.

SH: Finally, what do you hope to achieve with A Dutiful Boy?

MZ: I felt very alone growing up. I guess I want young people struggling with their identity to feel less alone. If it does that, then I will have succeeded.

A Dutiful Boy: A Memoir of a Gay Muslim’s Journey to Acceptance is out on August 20, 2020.