John Vaughan looks back at Raf Simons’ Spring/Summer 1998 show, which capsized traditional ideas of masculinity

‘This Unhappy Mansion’ isn’t the title of a Raf Simons collection, but it could be, conversant as the Belgian fashion designer is with extravagant angst and sprawling disquiet, the rooms they flock to, the doors they slam. The phrase comes from John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost just after Lucifer and his “horrid crew” of rebel angels are thrown out of heaven and condemned to suffer infinite sorrow “in the gloomy deep” which, I imagine, looks a lot like Simons’ Black Palms show. The ceiling soars and glitters, Alice by The Sisters of Mercy reverberates, spawns a dozen haunted echoes, and down the hall stalks Lucifer himself – or someone who looks a lot like him: a shaven-headed youth with flying buttress cheekbones, clad entirely in black, whose open shirt exposes a chest and stomach dappled black with – what else? – stars, marks you would expect to find on someone who has just crashed headlong through the cosmos.

The Show

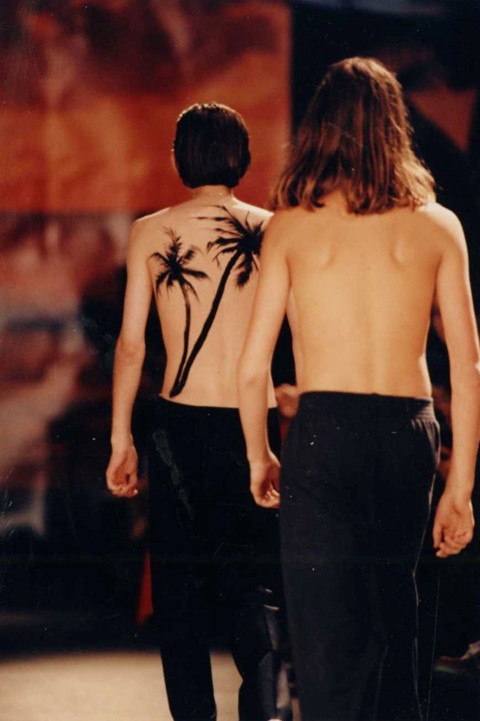

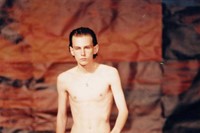

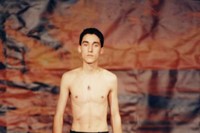

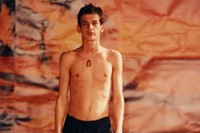

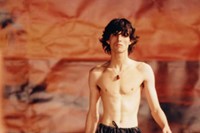

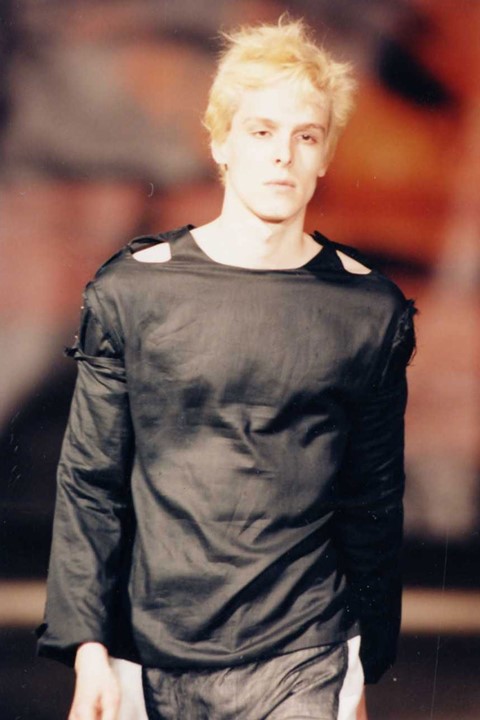

He appears in Black Palms, Simons’ Spring/Summer 1998 collection, and the stars, alas, are painted. Franky Claeys, the artist behind the collection’s graphics, flagged Apocalypse Now as an influence for the show’s torched aesthetic, but to me, its red-and-black palette recalls the 1981 USA print of Christiane F’s autobiography (which Simons has since paid direct homage to). For the show, Simons rented out this enormous echoing vault of a garage in the Bastille quarter of Paris and assembled a gang of beautiful young men to model his clothes – men, not models. They were mostly skaters, raver types Simons found through ads circulated on the radio, and the looks were dark, gothic, undone, in some cases literally bare, bones flashing beneath flimsy shirts unbuttoned and blowing wide open. Down the ramp they come: skulking, scowling, pale and scrawny, their movements slow and eyelids heavy as if still shrugging off last night’s lazy sex. Some of them are topless with billowing floor length pants tied loosely at their waists, some of them look shaken, half-sleep as though rudely startled from their coffins. Floss-thin bodies hewn close to the bone, pointy rib-cages in place of washboard abs, hair slicked back or falling forward in shining greasy locks: this was the brooding, vampiric correlate to the ‘sexed-out Studio 54 lotharios’ audiences were used to.

Before embarking on his now decades-long career in fashion, Simons studied industrial design and spent his time making furniture which might, at first, seem like a curious misplacement of his talents but it has been, and remains, a decisive factor in his work, since his entire oeuvre is a sustained effort in furnishing our dull, often lustreless exteriors with the riches resplendent within. It isn’t a huge leap from there to say that Simons art is one of sustained vulnerability – no small task considering he has worked largely in menswear, which values inviolability above all. In an interview with AnOther, Robbie Snelders, a model in the show and a muse to Simons ever after, noted that, for most people, “male models meant Marky Mark and this was something completely different. They didn’t understand what these skinny, pale, 60kg guys were doing in Paris for a show but then you saw it and it made sense.”

The People

I think what Snelders is trying to say is that by sending these boyish spectres down the runway Simons capsized traditional ideas of masculinity simply by presenting an alternative. Frequently torn and ravaged with holes (one model sports a black vest, sleeveless and slashed, á la Freddy Krueger, across the back in twin columns of vertebral slits), Simons designs anticipate and encourage a rough, enraptured contact with the world in which the threat of harm is welded to the possibility of ecstatic connection. Style like this becomes potentiality in the world, it opens, just like his clothes open, no, flay completely, in an instant revealing our quivering insides and showing them off like long-hoarded jewels, jewels which once lived quietly with the belief that they would go forever undiscovered.

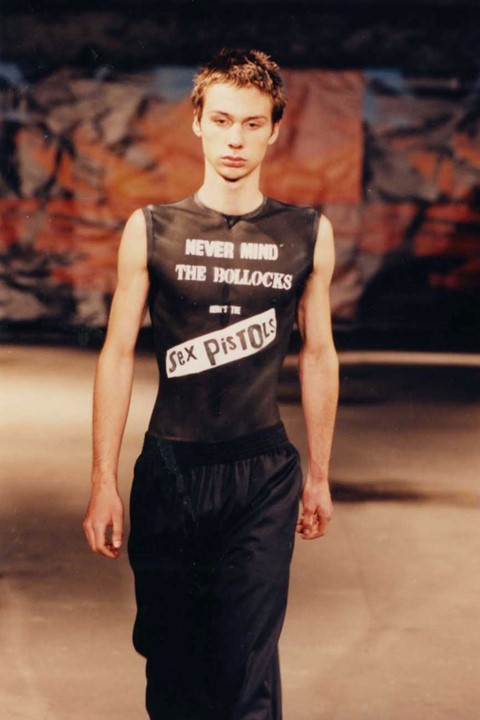

Before you can be discovered, you have to become visible, and therefore risk rejection, actual death. I think that’s what makes Raf Simons shows such revelatory events, because as the line that separates our style from our selves shrinks, so too does the line that separates ourselves from what we love. How else are we to read the model whose naked torso is entirely painted with The Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks album cover but that a layer of skin has literally flown off, that this, our excitement, our obsessions, this is what we’re made of.

The Impact

“I don’t want to show clothes,” Simons has declared. “I want to show my attitude, my past, present and future.” That he draws so openly from his own adolescence might explain the show’s enduring presence in the fashion world. As reported by the New York Times, “the skinny suit became the dominant shape of the late 1990s and early 2000s,” and while we may thank Helmut Lang for that silhouette, “the youth was all Simons’”. Since clothes, for him, are a continuation and reflection of our mutant, quickening selves, it seems right that they often resemble, in the best possible way, the most unruly, volatile and heaving of teenage bedrooms. If, as Kafka wrote, “everyone carries about a room inside him,” Simons has shown us how those rooms may be exhumed and unlocked, irradiated and explored to their innermost, most untidy quarters.