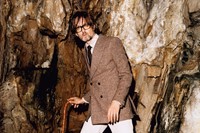

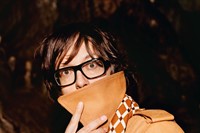

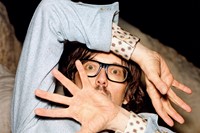

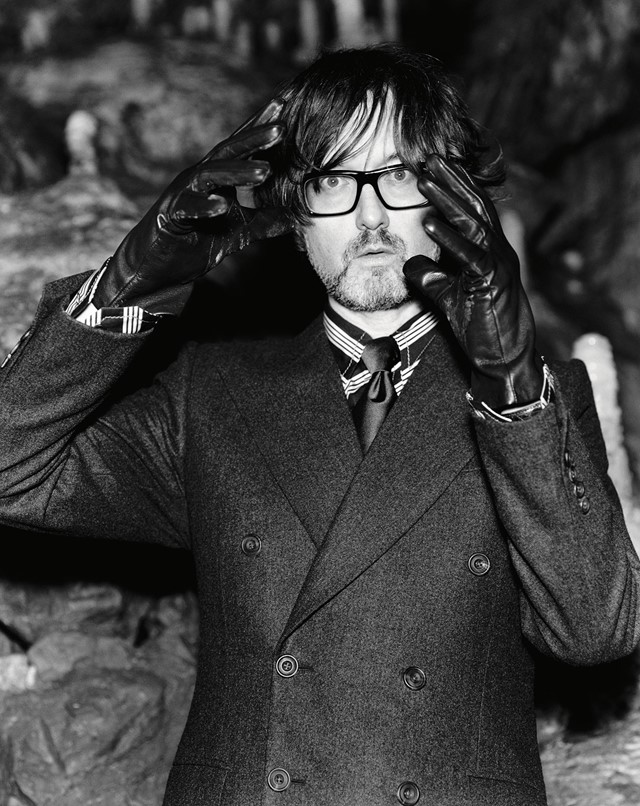

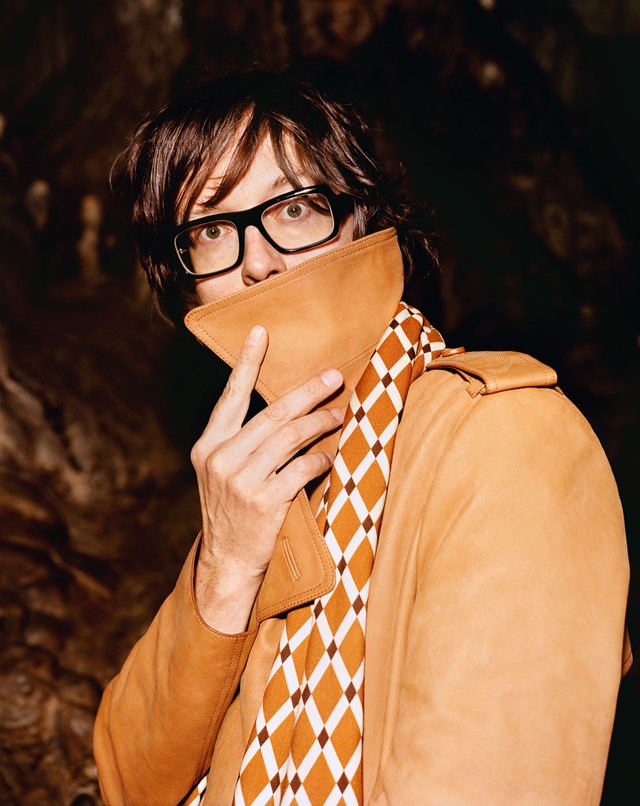

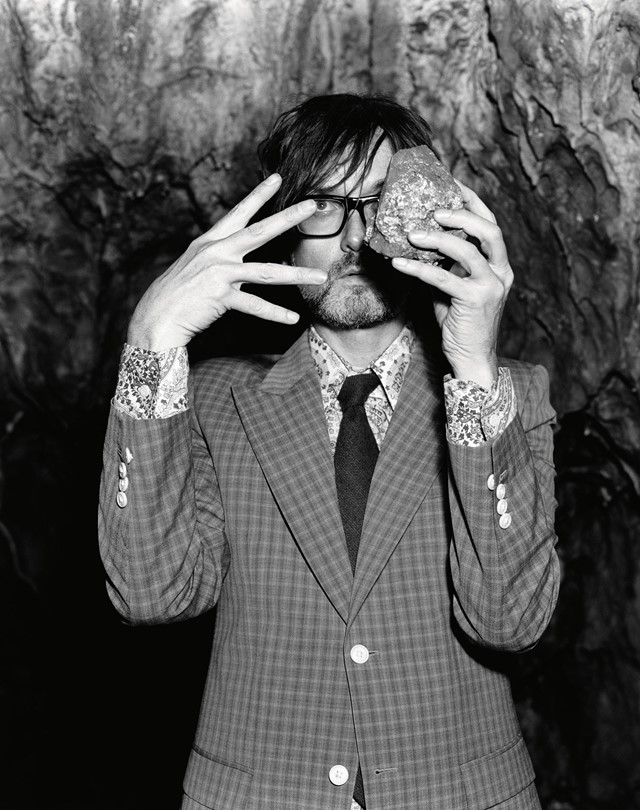

Inspired by twenties Hollywood and the Chateau Marmont, Jarvis Cocker and Chilly Gonzales' Room 29 is released this month. Here, the musician shares the stories that inspired the sound

What if you could spend an evening with Jarvis Cocker and Chilly Gonzales, all cosy and intimate in a hotel room? A room to which you had your own key? Complete with a piano, bedside table, TV set and some comfy slippers thrown into the mix (Gonzales’, not Cocker’s, bien sûr)? Well, now you can.

Enter Room 29, a new concept album written and performed by the two musical legends, and released this month by the prestigious German recording label Deutsche Grammophon. And, welcome to Room 29, a live show that is coming to London’s Barbican Centre between 23 – 25 March, having premiered at Hamburg’s Kampnagel in January 2016. Part musical soirée, part theatre play, part stand-up act, the show stages the songs from the album – not exactly accompanying it but rather living its own separate existence alongside it.

Conceived when Cocker had a serendipitous ‘encounter’ with a baby grand piano in a hotel suite at Hollywood’s Chateau Marmont, the album and the show shaped only gradually. The entire process was spurred on by research about the hotel and its surroundings that seemed to keep on giving. Since its opening in the early 1930s, one of Tinseltown’s most notorious hotels has witnessed numerous scandals and indiscretions of the movie glitterati, with Room 29 being especially resonant as the setting of a particularly infamous honeymoon between a certain peroxide star and her director-producer husband.

And so, while the room with the piano was the happy accident, the protagonist and the backdrop for Cocker and Gonzales’ storytelling, it is the moving pictures that emerge as the show’s true centrepiece. Overwhelmingly, Room 29 speaks about Cocker’s profound fascination with the movies, watched on screens large and small – a fascination traced back all the way to the beginnings of projected film strips. This is hardly surprising. Growing up under the spell of television and later studying film as an art student, moving images have long possessed Cocker, and this collaboration with Gonzales has become a process for him to tackle the enigma. Here he talks to us about it.

Marketa Uhlirova: What is the show about for you?

Jarvis Cocker: The idea is of a guy, who’s me, I suppose, in the hotel room on his own and the things that go through his mind. But actually, the main character of the story is a piano. That’s the device; Hitchcock would say the ‘MacGuffin’. In our mind the piano has been in the room since the hotel opened, and has seen all the changes that have happened. And because it’s a hotel in Hollywood, a lot of the stories it has to tell are about Hollywood. But then that develops onto my own story.

MU: Do you play the piano?

JC: No, that’s why I had to get Gonzales involved. I had wanted to work with him for a long time and then suddenly it became obvious that this was what we could do together. We had already worked together on another project. The film director Todd Haynes asked me if I could sing a Stephen Sondheim song I Am Still Here – it’s usually women over 60 who are asked to sing this – and I asked Gonzales to come up with an arrangement for that. On this project we worked together for three years – a long time – although I don’t necessarily believe that the longer you work on something the better it becomes. Sometimes things just don’t work. And we were lucky, it worked this time. It all came together. For me that was great. I’d been doing other things like presenting a radio show, but I have always thought my real job is to be a musician.

MU: Job?

JC: My calling. Having said that, it’s been great being able to bring into this new project all the aspects of what I do in the radio shows, all the research and having conversations with guests… But also my interest in film – I originally studied film at St. Martin’s… So this is my Magnum Opus [laughs].

“I don’t necessarily believe that the longer you work on something the better it becomes” – Jarvis Cocker

MU: Did you get involved with writing the music for Room 29?

JC: I didn’t write the music at all, though obviously I helped shape the melody with the singing. Some of the songs I just followed the melody he played. The way Gonzales structures songs is not the way I structure songs. I had to learn. I had to get into a different way of phrasing things. When we did get together, we worked very quickly, even though this record has taken such a long time to develop. The recording itself was done in about 10 days. And there was a lot of talking in between...

MU: How much did you feed back to him about what you were trying to convey?

JC: We wanted it to sound like something you could have recorded in a hotel room. We recorded it all in a small room, in a studio in Paris. And I hope that listening to the record feels like you are in a small domestic place. It was a bit like when Lars von Trier decided to make Dogme films. We decided there should not be any effects on the voice.

MU: In the early parts the album it feels like you are listening to a silent film accompaniment. And then it becomes a fully blown film score, when the orchestra comes in. Was this something you thought of at all?

JC: From the two solo piano records that Gonzales had done before, I’d always thought they sound a bit like something from the 30s, or from the early days of cinema. And that’s why I thought he was a perfect fit for this project. We talked a lot about cinema and the idea of cinema forming your perception of the world. I told him about my interview with the film historian David Thompson who wrote a fantastic book with the subtitle The Story of the Movies and What They Did to Us. He always talks about how the movies have affected humans and how they reflected what’s going on in society. The excerpts of him you hear on the record are from a long interview I recorded at the Chateau Marmont in 2014. I didn’t alter Gonzales’ music but I did work on the sequencing. For instance, I thought it was too much having song after song after song, because they are quite lyrically dense, so we came up with the idea of having interludes and the short bits, like the David Thompson voice excerpts. Or sound effects, like the noise of the hotel lobby or elevator... All that was trying to give the record an environment.

MU: At which point did you start talking to Chilly Gonzales about working with film?

JC: Initially, I was wondering what shape this project would take, and we briefly thought it could become a film. I presented to Channel 4 and they gave us some development budget, with which we shot the footage at Chateau Marmont. But at that point I already had the idea of using bits from old films. And so I just trawled through YouTube and came across footage of the serpentine dances. I thought it was interesting to go back to the very early days of cinema because then people hadn’t seen very many moving images, and I thought the things they latched onto could tell us something important about what we like about film. I had never seen the serpentine dance before, the footage is so beautiful to look at. Obviously, part of it is a sensual gaze – it’s women performing these dances – but it’s also just the beauty of the shapes they make. And the way the camera maybe reveals more of the dance than what you’d see if you were watching it. You get the first inkling that film can alter reality. It doesn’t just capture it. The process of capturing it alters it in some way and maybe you can also enhance reality.

MU: It’s true that film brings something out of the dance that’s different to watching it on stage. Even just for the fact that film is recorded image…

JC: That was the magic of film at first. For the first time you could re-live a moment. And what I also love about these films is that for something that’s 120 years old, they communicate with you really directly, they feel very contemporary... You know, films with Charlie Chaplin are very much period pieces in comparison.

MU: In your album there is also a strong theme running through of Hollywood actresses and actors, or producers, of the 1920s and 30s. How did you become interested in all of this?

JC: I’d had this book called The Hollywood Handbook since the mid-1990s, which is edited by André Balazs, who owns the Chateau Marmont. It’s a compilation of writings, some specifically about the hotel, and some about the surroundings. So the stories of Jean Harlow and her honeymoon, and Howard Hughes, are featured in that book. Somehow, this stuck in my mind. So when I then stayed in the room and talked to the general manager about the piano, and he said he didn’t know how the piano came to be there but he knew that’s where Jean Harlow had her honeymoon.

“I thought it was interesting to go back to the very early days of cinema because then people hadn’t seen very many moving images, and I thought the things they latched onto could tell us something important about what we like about film” – Jarvis Cocker

MU: Do you know Kenneth Anger’s book Hollywood Babylon? Your project made me think of that.

JC: Yes, I actually interviewed him for this project but I didn’t use the recordings. The next day, I interviewed David Thompson, and ended up using excerpts from that. I know Hollywood Babylon but I didn’t want to go too far into the whole excessive behaviour thing because it’s been done, and then it starts to read like Heat magazine, or Jackie Collins. My feeling is that in the silent period, going to the cinema was a bit like going to church. People had to leave the house… and then they sat in the dark and something big happened – big, literally, because the images were big. But also big in the sense of all the fantasies that were in people’s subconscious. Actors looked amazing and something amazing could happen. I think the cinema brought things out. Before those screen goddesses people didn’t know women could look so great – or men for that matter. Or house interiors. I think it really inflamed an appetite to expect more from life.

MU: This project is not about cinema per se so much as it is about your personal response to the cinema. Was Chilly Gonzales involved in this too?

JC: Yes, we talked about this stuff a lot. He lent me a great book called The Power of Movies: How Screen and Mind Interact. We both thought it was relevant to talk about this now. We are surrounded by moving images and yet we are so blasé about them now. These days the moving image is just one of the things your computer does. Before the magic was that you could capture reality. Now the moving images are our reality and people pick up their cues on how to live and how to act by watching the film. The cart has gone in front of the horse.

MU: What gave you the biggest pleasure in this project? Where did you get your high from?

JC: The pleasure of creating things is that you discover what something means in the process of making it. The piano at Chateau Marmont was an incident that spurred the idea, but then you have to find a way of making that idea into something, and that takes time. Even the show we did in Hamburg last year we have altered a little bit since. And I don’t feel I got everything from it yet. When we do the next shows I’ll find out something more about it. For me, that’s how I find out things about myself. I think about things a lot but intellectual activity is only half of it. A lot of stuff is subconscious and to get the stuff out, that’s why we create things…

Room 29 by Jarvis Cocker & Chilly Gonzales is out now.