We reveal the story behind Man Ray’s iconic Noir et Blanche, one of the most important examples of Surrealist photography

This month marks the release of a trilogy of photo books by Taschen, each dedicated to an American 20th-century photographic “master of light”: Man Ray, Paul Outerbridge and Edward Weston. Here, in the first of a three-part dedicated series of features, we explore the story behind an iconic pair of images from the first: Noir et Blanche by Man Ray, “the multitalented master of Modernist imagery”.

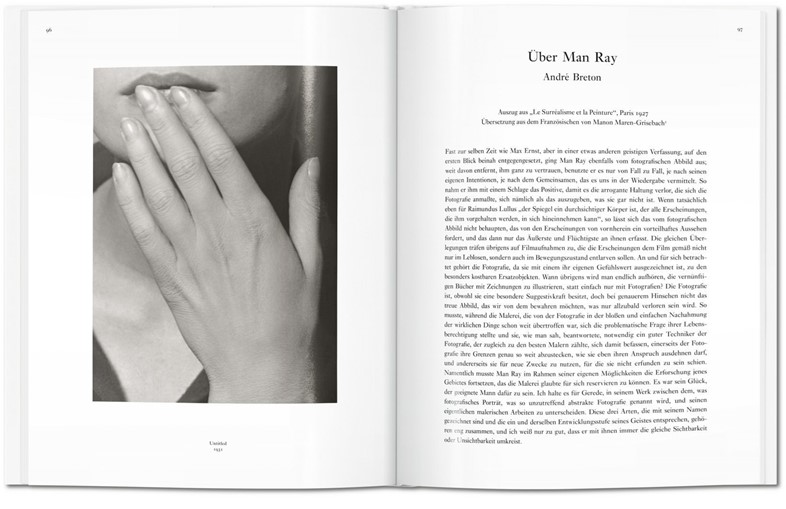

When young American painter and photographer Emmanuel Radnitzky, better known as Man Ray, followed his friend Marcel Duchamp from New York to Paris in 1921, he finally found himself among likeminded souls. The experimental pair, who met in Ridgefield, New Jersey in 1915, had been busy trying to pioneer Dadaism in the Big Apple, co-editing the magazine New York Dada, which turned out to be an epic failure. Thus followed their move to Paris, where the rest of the Dada group were residing, and Man Ray’s life-changing introduction to André Breton, Jacques Rigaud et al on July 22, 1921. Breton saw in Man Ray a useful accomplice, employing his photographic skills to capture artworks for inclusion in Breton’s magazine Littérature in return for publishing Man Ray’s portraiture. Through this, and word-of-mouth recommendation, Man Ray had soon been introduced to all of Paris’s key players, from Gertrude Stein, Picasso and Jean Cocteau to the many wealthy aristocrats keen for a portraitist. Eventually he came to the attention of couturier Paul Poiret, and by 1924 was regularly photographing Parisian haute couture for Vogue.

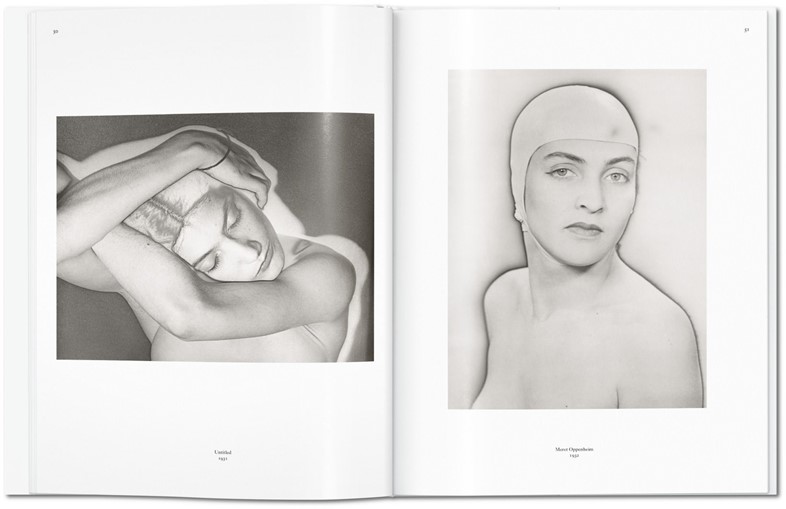

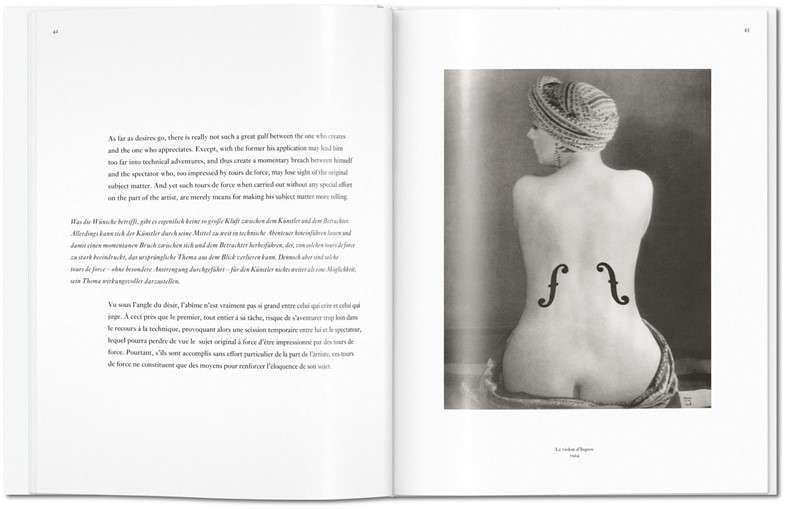

Man Ray never approached photography in a traditional manner. For him – a self-proclaimed painter, first and foremost – it was a medium ripe for manipulation. In late 1921, he developed his eponymous “rayograph” technique – the result of accidentally switching on the darkroom light mid-development – a process that creates a reverse image of a photograph in which the light and dark areas are dramatically switched. His early images using the method are widely credited as the first instances of Surrealist photography. Perhaps surprisingly, the fashion world were enamoured by this artful doctoring, which they saw as elevating the status of photography to that of an art form, and in 1922 Vanity Fair included a four of his rayographs in a feature. Man Ray was delighted by such widespread dissemination of his work and not long after proclaimed that he would always “combine art and fashion” in his commercial projects.

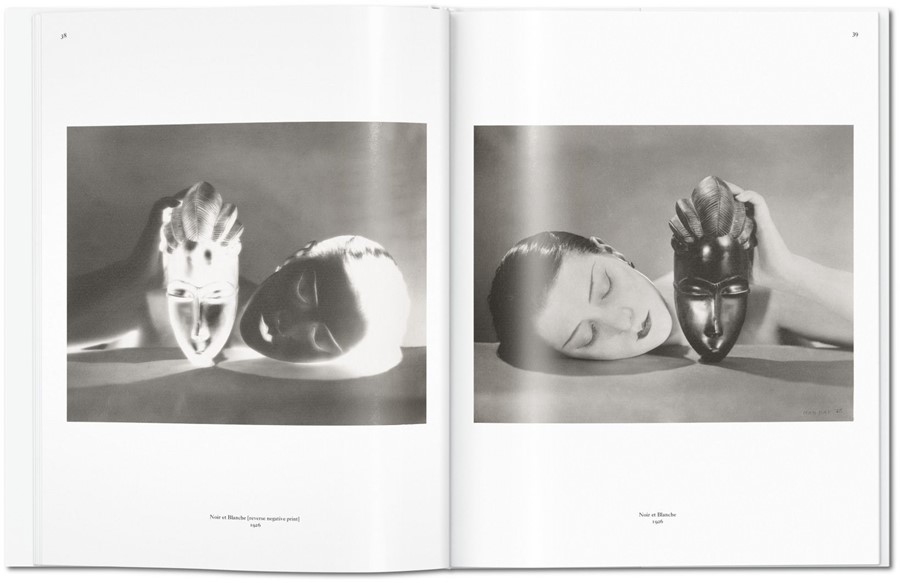

As a result, many of his most revered works were in fact taken for fashion magazines, including his seminal 1926 image Noir et Blanche, and its reverse negative print, depicting Man Ray’s muse Kiki de Montparnasse, her pale face resting on a table and her hand holding up a wooden African mask whose beatific expression she is mimicking. The duo had met in 1921, when Man Ray, allured by the actress and singer’s “cute accent and air of mystery”, had asked her to pose for him. The pair lived together for a time as lovers but eventually separated, although Montparnasse continued to model for him on and off for many years.

This iconic image first appeared in the May 1926 edition of Vogue, alongside the evocative caption “Mother of Pearl Face and Ebony Mask”. It is a majestic study in tone and texture: the patches of light on the dark, lustrous mask are echoed by those punctuating Montparnasse’s shiny black hair, while, in contrast, her soft, porcelain-hued face and shoulder boast delicate patches of shadow. These juxtapositions are masterfully highlighted in the reverse negative, in which the mask and Montparnasse’s hair (including her eyelashes and brows) and rouged lips radiate light while her skin is the colour of charcoal. These two enduringly powerful images – which would go on to inspire Jean-Baptiste Mondino’s 1999 advert for Jean Paul Gaultier's signature Classique – embody the words of Emmanuelle de L’Ecotais, who writes in an essay for the Taschen tome, “Man Ray wrote with light bulbs just as poets write with pens. White light replaced black ink. Man Ray became the supreme poet, writing with light.”

Man Ray, edited by Manfred Heiting, is available now, published by Taschen.