“We have a new, long-awaited artwork called The Fuckosophy,” says George with some glee.

“The Fuckosophy!” exclaims Gilbert, laughing.

“It’s pushing 4,000 lines,” says George. “We read out an extract in Paris.”

“Two pages,” says Gilbert. “It was quite exciting. Everybody was sitting.”

George: “All smoking!”

Gilbert: “Everybody was sitting, so we stood up...”

George: “Which alarmed everyone. They don’t even sit up!”

Gilbert: “We read for eight minutes, The Fuckosophy.”

George: “The first few minutes they giggled a bit. Then they got quiet. And then some of them got very alarmed.”

Gilbert: “Some of the French artists got very excited. Totally excited by it!”

George: “Nobody actually reads philosophy. There is no philosopher in the village, like a village shop or a village pub or a village church. So we decided to create a philosophy that actually extends to every moment of life that you might hope or fear for; dying, living, getting married, whatever happens in life, we are trying to cover it. There are 3,589 lines so far.”

The artists then launch into an impromptu performance of an extract from The Fuckosophy, taking it in turns to read out each line.

George: “Got fucked and fucked.”

Gilbert: “Fuckridge.”

George: “They’re fuckers.”

Gilbert: “Fucking Sussex.”

George: “Regimental fucking.”

Gilbert: “Fucking chapel.”

George: “Wanker fucker.”

Gilbert: “Fucker’s estate.”

George: “Don’t fuck up.”

Gilbert: “Fucker’s wharf.”

George: “Onward Christian fuckers.”

Gilbert: “Fuck the checkpoint.”

George: “Really beautiful fucker.”

Gilbert: “Fucker’s drift.”

George: “Unpleasant fucking.”

Gilbert: “Fucking descent.”

George: “The fuck diaries.”

Gilbert: “Fucker’s Wapping.”

George: “Cookie fucker.”

Gilbert: “Fucking in the North Korea.”

George: “Country fuckers.”

Gilbert: “Fucking special.”

George: “Holy fuck.”

Gilbert: “Fuck the shit out of them.”

George: “A couple of fuckers.”

Gilbert: “Fucked once.”

George: “Judge fuck.”

Gilbert: “Fuckers have feelings too.”

George: “Dellefucker.”

Gilbert: “Fuck, fuck hooray.”

George: “Don’t stop fucking.”

And so on. Much rests on the duo’s delivery.

“It lasts an hour and a half. We’re going to make a record,” explains George. “We expect The Fuckosophy to be like muzak, repeating endlessly. We carry cards with us and jot them down when one comes to us. We say it, hear it and think it.”

“And now we have builders here...” adds Gilbert, clearly pleased with their artistic contribution to G&G’s “Art for All” manifesto.

Each encounter with Gilbert & George is to some extent a work of art in itself. Their entire beings have been devoted to their art since they first met in 1967 on the famous sculpture course led by Anthony Caro at Saint Martins School of Art, as it was then. Always against the grain, as young men – then barely in their twenties and, as George might say, “baby artists” – it was there that Gilbert Prousch and George Passmore began to turn themselves into living sculptures and monuments to their own art. Next year will see the 50th anniversary of that fateful meeting, and the beginning of the highly serious endeavour of turning their very existence into art. Nevertheless, this task has always been accomplished with wit, charm, toughness, kindness, and fortitude. Gilbert & George are two of the most delightful and touching people you will ever meet – and neither is a pushover.

This year is the 35th anniversary of the work that perhaps expresses the duo and this endeavour in the clearest, most lyrical, entertaining, and profound way. The World of Gilbert & George was completed in 1981 and in many ways it is the artists’ magnum opus. It is a film that deals with identity, patriotism, duty, sacrifice, life, death, sex, and religion. It encompasses so many of Gilbert & George’s preoccupations, so familiar from their monumental art works, and yet it has an intimacy and poetry that you will often only find when speaking to the artists themselves. It is a film that seems even more resonant in post-Brexit Britain – although this present conversation with the artists takes place before the votes in the referendum have been cast. The film is set in London, mostly in their house in Fournier Street in Spitalfields, east London – the site of their studio and home for many years, and where this interview is held.

As evidenced by the film, the changes that have taken place in the capital are quite startling, yet this change and its observation is something that Gilbert & George relish. Somehow, they themselves remain detached, unbowed and unsullied by it – their task at hand as artistic observers is far too important for experiments in dress, deportment and dining. Gilbert & George knew who they were at a very early age and stuck with it. Like the blind prophet Tiresias in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, they have “foresuffered all” and yet they are the only ones clear-sighted enough to be able to explain this moment in time to everyone else.

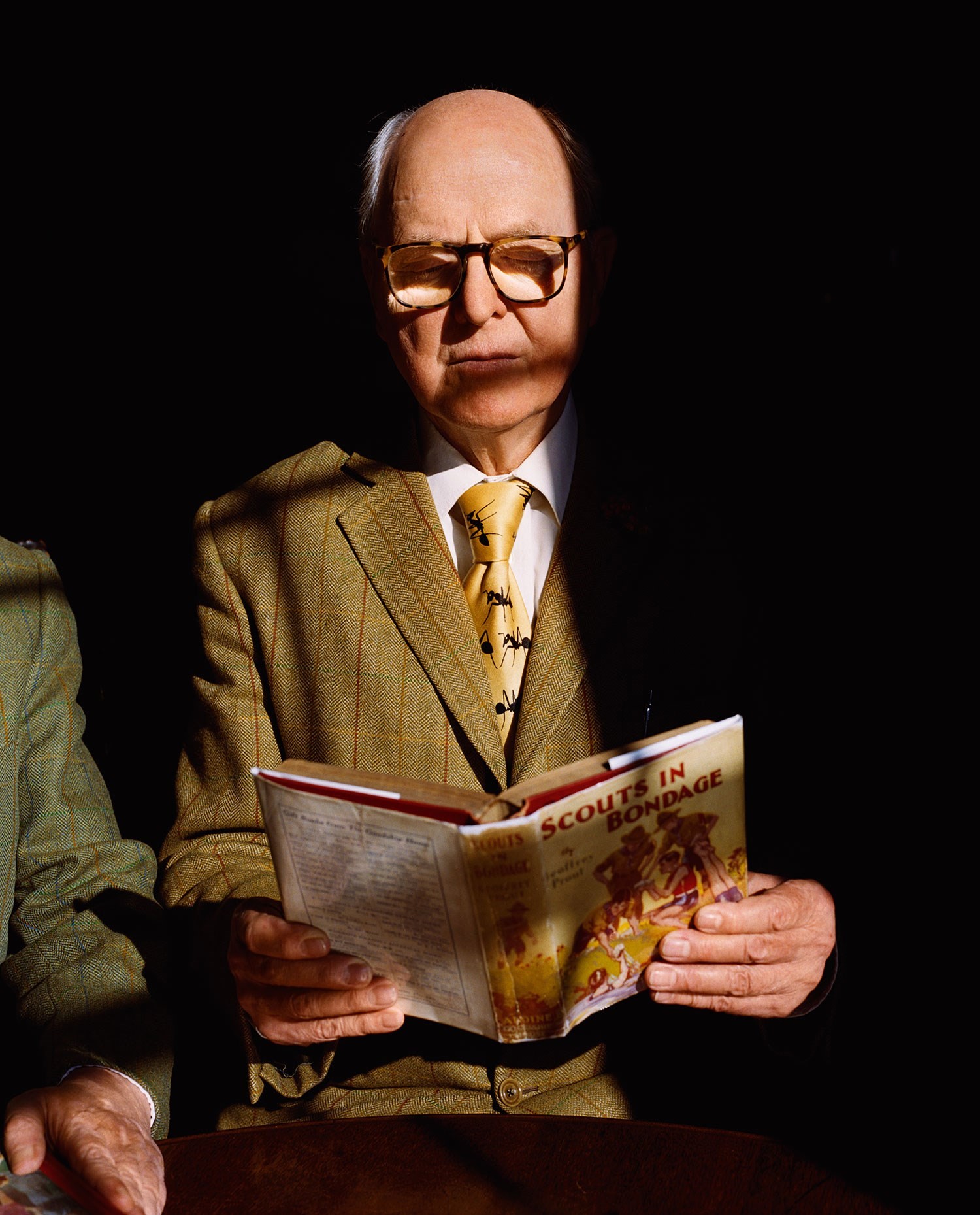

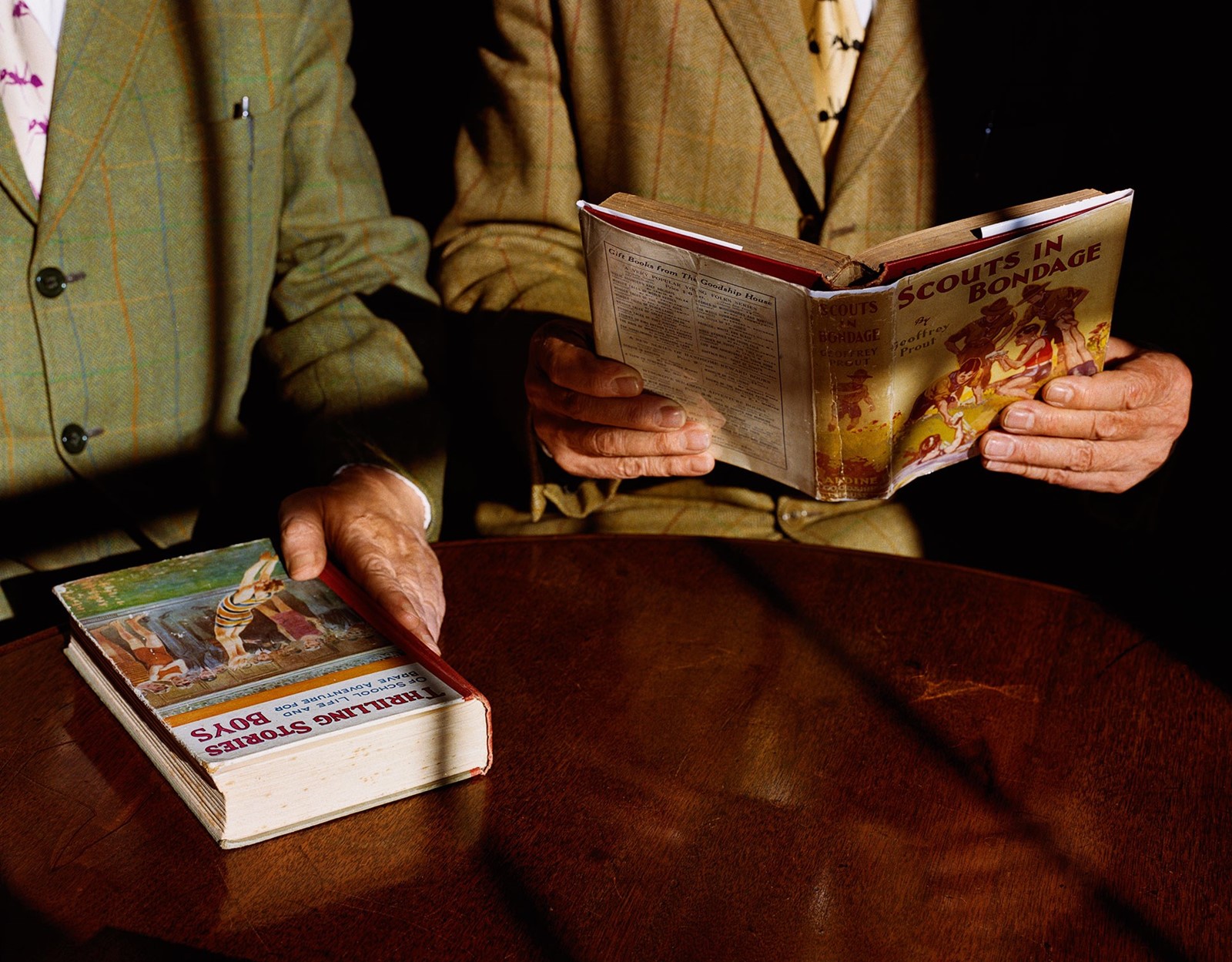

Then, as now, the East End is the artistic crucible for the duo, the centre of their world and the prime target for their ambitions of an “Art for All”. All human life is here, and above all, G&G are humanists, something lost from much contemporary art. It is the site of their self-imposed exile, their outsider status, and the studied strangeness of their lives that makes it possible for them to complete the work that they do. Their regimented habits of dress, work, and sustenance – they continually eat out, as, until recently, they had no kitchen – are all catered for in this small part of the London sprawl. Surrounded by their fantastic Pugin, Dresser, and Godwin Arts & Crafts furniture – including a chair with their new “crest” embroidered upon it and featuring a pubic louse; their vast array of beautiful books, including a library for boys with titles such as “Scouts in Bondage” and “From Fag To Hero”, which they delight in showing guests; and their endless filing systems for their work and articles about them, it is a place of strange order and tranquillity. “We feel very privileged. We can go out, have breakfast, come back and do exactly what we want,” says George. “We don’t have to ask anyone’s permission to do anything.” “And we do not have people here!” adds Gilbert. “We have one Chinese boy who followed us.” This is their able assistant, Yigang Yu, “And that’s it.”

In certain ways, their existence seems quintessentially English and from another time. And yet, as George exclaims of Gilbert, “He’s Italian!” Indeed, George has the ultimate RP accent, while Gilbert has a more explosive Italian intonation.

“You can be alone and be part of everybody here,” says Gilbert of his adopted home.

They both agree that being part of the living history and continuity in London has shaped their identities. Watching the Trooping the Colour is “The best thing in the world” for George. “Going to the Cenotaph is extraordinary,” says Gilbert.

“And that’s where we differ from the rest of the art world,” explains George. “Protesting hippies! There is a big difference between us and them.”

Indeed, they have no time for the sloppy-looking Jeremy Corbyn. “If you walk the streets of London, you never see anybody who looks like David Cameron,” says George. “But you do see thousands of people who look like Jeremy Corbyn. Really. If we went to the restaurant we always go to each evening and put up a picture of David Cameron, people would stop going. But if we put up a picture of Jeremy Corbyn, they’d like it.”

We are looking at the opposite end of the studio, where a David Cameron poster takes pride of place. But do they really like David Cameron?

“We think he is a very fine person,” says George. Really?

“Yes,” they insist together.

Even after the pig fucking?

“He did that in a good way!” exclaims Gilbert.

David Cameron is clearly one of the duo’s heroes and they will not be swayed. Another is Prince Harry. “Harry is fantastic,” says George. “He is a great model for many young people. He’s highly trained. Highly trained – not many people get to that level.” Although the duo are not always in complete agreement...

Gilbert: “And George, his favourite at the moment is George.”

The royal baby?

Gilbert: “No, George Osborne.”

George: “I think he is pure glamour. And he has both money and position.”

Gilbert: “It’s very funny. A few years ago he was a little fat, but now he looks like a ventriloquist’s dummy.”

George: “He’s a matinee idol for me.”

So you actually have a crush on George Osborne?

George: “Of course. Well, if I am going to have a crush it may as well be on somebody important.”

I wonder who Gilbert has a crush on.

Gilbert: “I would have to think about that.”

George: “Theresa May!”

Later on, George Osborne makes an appearance – in paper rather than in the flesh. He sits under glass on a table used by the artists to open their post in the morning. On this “table of pin-ups” he is joined by Colonel Gaddafi’s playboy son, Saadi; Oscar Pistorius; Ivor Novello; and a boy kissing a turtle – that one is for Yigang Yu, who loves turtles. It is not known if George Osborne has now suffered a demotion from the table similar to that from the backbenches, no longer enjoying the position and power he once did with the artists. And how prescient George was about Theresa May, even if he was only teasing Gilbert.

“I believe in the art, the beauty and the life of the artist who is an eccentric person with something to say for himself. I uphold traditional values with my love of victory, kindness and honesty. I am fascinated by the richness of the fabric of our world and I honour the high-mindedness of man as the ultimate form and meaning of art. Beauty is my art.” – From The World of Gilbert & George (1981)

Gilbert & George are certainly kind and honest, but do they believe they have been victorious in their art?

“We liked it recently when a large truck slowed down on Commercial Street,” says George. “And the big, shaven-headed, middle-aged driver leaned out and shouted, ‘Gilbert & George! My life is a fucking moment, while yours is an eternity!’ Rather moving I thought.”

“It means that what we do is working,” says Gilbert. “And it is working! We put our pictures up and people think, ‘Who did that?’ But everybody seems to know us as we walk along. As we walk to dinner in Dalston people stop to have their picture taken with us. Art is very big at the moment. It is part of the entertainment industry.”

“It’s official. All the world is an art gallery,” says George. “We said that in 1969; that we wanted all of the world to become an art gallery. And it’s happened. Every side street around here has an art gallery. It’s extraordinary.”

They got their wish. How do they feel about that?

“We don’t want the old days back,” replies George. “If you asked a person in 1970 to name an artist, they might say [affecting a cockney accent – George is an incredibly good impressionist] Michelangelo or Leonardo. They did not know a living one. A living boxer, a living murderer, a living paedophile they’d know, but not a living artist. It’s quite shocking. It was a very poor diet.”

“Now there are so many artists,” says Gilbert. “It just used to be the European and American art world, now it’s different. Now an artist can be from anywhere, from the Himalayas, from South America... That’s why we believe that we have to concentrate on just being us. Just us.”

They have created their own world.

“It is the vision, the world vision that we have created,” Gilbert continues. “A lot of modern artists are not doing what we are doing. For us, the centre of our art is a human being. The others have a formalistic attitude, of nice colours and nice shapes. We have a moral dimension: what is good and what is bad in people.”

It is indeed a triumph for their art, away from the easy art of found objects, abstraction and fashionable knick-knacks. Or as George puts it: “The fact of the matter is that nowadays you cannot be a young man or a young lady and invite somebody home unless you have a blank canvas or a funny sculpture there. You will not have sex with anybody. We see it from the top of the 67 bus in the evenings – there is always a blank canvas over the sofa.”

On the contrary, what preoccupies G&G more and more is religion, or rather their dislike of it. Which is strange, as the artists over time have become almost sacramental figures themselves. Aiming to remove themselves from the surrounding world, their lack of friends – they frequently mention how “alone”’ they are – and their concern for humanity conveyed through their work, there is almost an ascetic suffering by the duo. They may well be suffering for our sins on the top of the 67 bus.

Gilbert: “Stylites. In France they always call us ‘Stylites’.”

George: “Stylites. They made us stand on the top of a column for years. And never come down.”

Gilbert: “And never change.”

George: “We always said sex, money, race, and religion. They’re involved in everything we do; speak, eat, drink, love. It’s always those four things.”

Gilbert: “It’s very funny, because you realise religion is only based on opinions in some way. That’s it. That’s where the problem is. Religion is about laying down the law of what you are allowed to do and when you are allowed to do it.”

George: “To this day. Even the Catholic gay adoption uproar is all about that. Like you’re doing something funny with your penis.”

Gilbert: “Or if you go to Africa, the witch doctors are the same.”

George: “Female circumcision. In Britain. Today.”

Gilbert: “I’m sure if you went to India the Hindu leaders would be the same.”

So why are they called – what was it again? – in France?

Gilbert: “Stylites? Don’t know.”

George: “They were in Syria on this column forever. Their whole life.” [He’s referring to the Christian ascetics, the Stylites, who mortified their bodies by living on top of pillars.]

Gilbert: “The shit piled up, the shit piled up. No change, and then they became tanned and then dark and then blue and strange colours...”

George: “Then they would chuck up food...”

Gilbert: “People would supply them with food in a basket.”

George: “In India they have these holy men who stand by a tree and the tree grows around them so they can never come out.”

Do they feel they are a bit like that?

George: “No, the French just invented that about us, I think.”

Gilbert: “But I think we are in some way, because we became totally alone. Not that we wanted it at the beginning – it just happened more and more, don’t you think?”

George: “They drove us to it.”

Gilbert: “We don’t like to be trapped by people. We don’t like to go to many places.”

George: “Restaurants are OK, but not houses.”

Gilbert: “We don’t like houses.

George: “You can’t leave, can you? Not the way you can leave a restaurant.”

Gilbert: “And we always have to perform.”

George: “Yes we want to be relaxed and go to dinner alone.”

Gilbert: “It’s very good because we’ve created a world for ourselves. At 6:30 we have to leave the house for breakfast. George reads dirty books at five o’clock.”

George: “The thing is, in the summer we sit in the front room in the window – there’s a beautiful light coming in and our new vicar jogs past, because he’s a modern vicar. One day he stopped me in the street and said, ‘It’s so nice to see you reading your books in the morning.’”

Gilbert: “Every night George walks for one and a half hours and I walk for 45 minutes and we meet at exactly eight o’clock at the restaurant.”

George: “If I arrive a minute early they say, ‘Where’s Mr Gilbert?’”

Gilbert: “It’s very funny because we always take the 67 bus back, at the top of the bus, at the front. We are driving the bus in a way. And then we are near Shoreditch where all the nightclubs are, and there are long queues outside the nightclubs. They all can see us. They look out for us. They always spot us and we always wave.”

George: “They take pictures with their mobile phones and all the others are thinking, ‘What’s going on?’”

Gilbert: “And that’s very funny.”

I remember seeing them outside the South London Gallery when I lived in South East London. Their movements were exactly in tune with each other, I tell them.

Gilbert: “That was a long time ago.”

George: “Peckham Rye is probably the place you’re trying to think of.”

Gilbert: “Peckham Rye, yes, because we were talking about William Blake.”

George: “William Blake saw Lord Jesus in a tree there, in Peckham Rye.”

Gilbert: “We used to buy design magazines, design books, and one day a company came with an original William Blake book. We actually didn’t want to buy it. We don’t like to buy art. But we bought it – it’s an amazing book. There are these amazing skinheads with wings.”

George: “Much more of the planet Earth.”

Gilbert: “Much more of the planet Earth. It’s amazing. And there is this amazing Jesus with big nails – but they are so big, the nails.”

George: “Like something out of a DIY shop now. Cruel.”

Gilbert: “Oh, he’s magical, William Blake.”

George: “Albion!”

Gilbert: “Albion.”

George: “Sex and religion.”

Gilbert: “Sex. We’re all sex. And religion.”

This article originally appeared in AnOther Magazine A/W16. Gilbert & George: THE BEARD PICTURES AND THEIR FUCKOSOPHY opens at White Cube Bermondsey on 22 November 2017.