On the release of her new book, Grace Banks presents five artists using plastic bodies to subvert the misogynistic representation of the female form

Over the last few years, a growing group of artists have been subverting sexist materials, from sex dolls to mannequins, to unravel the misogynistic representation of women’s bodies in contemporary culture. In my new book, Play With Me: Dolls, Women, Art, I wanted to bring together a group of these artists who view dolls as the ultimate objectification of a woman’s body, and look at why their work is tied so tightly to the politics of millennial feminism.

These artists are taking back the right to create the female nude on their own terms, male gaze-free. Between them, they pave a new way for women in contemporary art who, in largely working offline, show a triumph of real life feminism over clickbait activism.

1. Elizabeth Jaeger (above)

In this piece, Maybe We Die So The Love Doesn’t Have To (2015), Elizabeth Jaeger’s use of latex paint and plastic hair create a superficial aesthetic. Using the doll-like, almost cartoonish, guise of these figures, Jaeger takes a look at the roles women play in public, and how those roles came to be. Her interest in the human body started when she was working as a photographer in her early twenties in New York, and many of the poses she now sculpts her female nudes in are references to these photographs.

2. Stacey Leigh

A Playboy magazine report in 2014 praised Leigh’s work for bringing the appeal of an inanimate female doll made for sex to life, but what she achieves in her photographs is far more serious. Staging her series of bespoke Real Dolls in fashionable clothes, at political protests or at home in isolation, Leigh encourages the viewer to see how different a medium used to represent women can be when a man uses it, compared to when a woman does. Leigh realised that authored by a woman, these dolls were a powerful new tool of female representation.

3. Annie Collinge

London-based Collinge’s series of photographs Five Inches of Limbo takes its name from the last line of a series of five poems by Margaret Atwood about dolls. The poems describe the varied but ambivalent and ambiguous relationship we have with dolls as children, and later as adults. Collinge’s photographs tap into the “fresh perspective of the idea of a doll” in Atwood’s poem and draw similarities between real women and dolls. Collinge enjoys subverting the original use of these plastic bodies: “I liked the idea that a doll is something taken from reality; I wanted to use an image of each doll to turn it back to reality and see how it mutated in the process.”

4. Mira Dancy

In her neon relief Call from Violet, Mira Dancy mimics the tired trope of neon ‘Girls Girls Girls’ signs and manipulates it for her own benefit, creating a sexy reclining nude that’s exposed purely on her own terms. Dancy, who is prolific supporter of Planned Parenthood, says of her work: “These are images made from the perspective of being looked at as a woman. Seeing and studying images of women made by men, I was trying to find a way to liberate this body from object status. And once I’d done that, what this could possibly mean.”

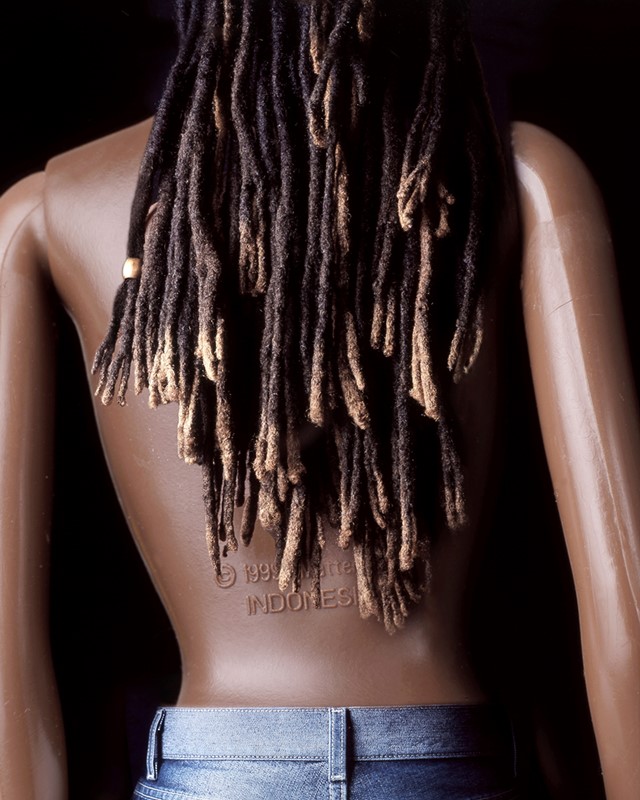

5. Sheila Pree Bright

A prolific activist and photographer, Pree Bright called out the racist and sexist standards of Barbie dolls in her series Plastic Bodies. She got the idea for this series when she stumbled across a picture of the Hottentot Venus, a woman brought from Africa to England in the 19th century as a spectacle of African womanhood. It was then that she “realised not much has changed; women’s bodies are still exhibited by men”. For Plastic Bodies (2014), Bright street cast strangers from Baltimore, combining their human bodyparts and features with that of a Mattel Barbie doll.

Play With Me: Dolls, Women, Art by Grace Banks is available now, published by Laurence King Publishing.