The late Maurice Broomfield’s photographs of postwar industry look more like the work of avant-garde modernist Man Ray than depictions of dirty, noisy workplaces.

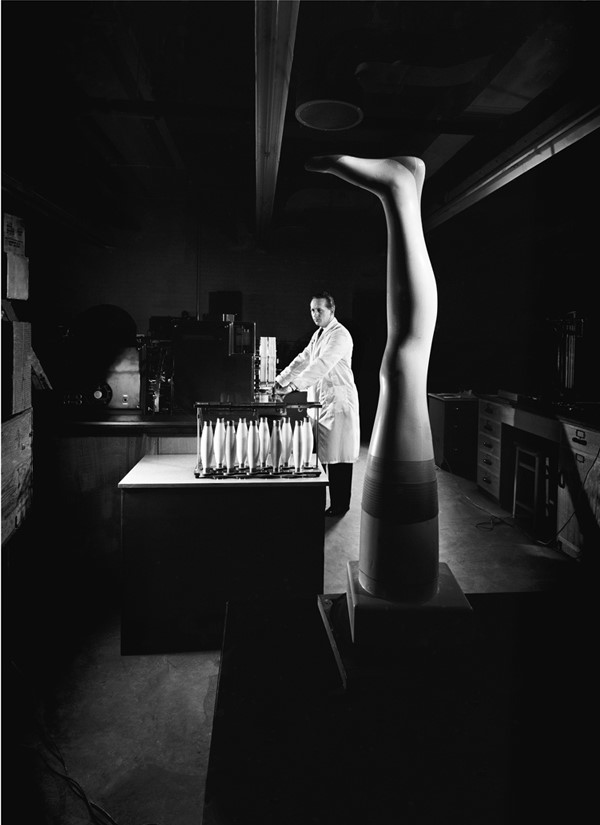

The late Maurice Broomfield’s photographs of postwar industry look more like the work of avant-garde modernist Man Ray than depictions of dirty, noisy workplaces. His visionary studies of the industrial boom from the 50s up until the 80s perfectly embody the Bauhaus maxim that beauty really can be found in function and offer a window on the strident spirit of optimism when Britain really was the ‘Workshop of the World’. To celebrate this period of work, and the rich industrial heritage of the Black Country, West Bromwich gallery, The Public, is currently exhibiting a collection of 25 Maurice Broomfield photographs co-curated by Broomfield’s son, award-winning documentary filmmaker, Nick Broomfield. “Maurice and I had been working on a large format exhibition of his work just before he died", he explains. “Many of the pictures taken in British factories in the early 50s were taken on big format cameras, with lots of dramatic lighting, so they really need to be seen big to have the full effect.”

Born in Draycott, Derbyshire in 1916, Maurice Broomfield left school at 15 to work as a lathe operator on the Rolls Royce assembly line. His evenings were spent at Derby Art College where he would discover the talents that that would lead to his narrow escape from life on the factory floor. Returning from a photographic trip around Europe after the war, a lucky introduction led to an invitation from ICI for Broomfield to take photographs of their factory and its workers. The starkly lit, black and white portraits quickly caught the attention of other industry leaders and he was soon taking commissions from equally prestigious corporations for their annual reports, exhibitions and trade fairs. Inspired by the drama of industry and moved by the skilled and noble nature of the factory operatives, Broomfield transformed otherwise mundane, everyday scenarios into theatrical and often otherworldly homages to Britain’s factory workers and emergent technology. Between 1954 and 1960 he was publishing a photograph a week in the Financial Times and regularly curating and exhibiting at the Royal Photographic Society. Despite success, Broomfield admitted to a sense of unease about the alternative reality belied by his varnished compositions; a life that was often dangerous and mind-numbingly boring, a life he very nearly had. He maintained, however, that any lesser presentation of the workers would have been a great disservice to them.

Though Broomfield made an immaculate transition from monochrome to colour in the 60s, as assembly lines became increasingly automated in the early 80s, his interest in photographing manufacturing production dwindled and he returned to his first loves: drawing and painting. Following the death of his first wife in 1982, he never took another industrial photograph, but continued to work up until his death in October last year. Nick Broomfield concludes, “My father was an enormous inspiration to me. His sense of poetry and romance are so alive in his pictures. He celebrated life and so do his pictures.”

Maurice Broomfield – Industrial Photographer and In the Best Light, a collection by local photographers, runs at The Public until 26 June.

Text by Melissa Osborne