Elizabeth Heyert travelled extensively to document China’s complex relationship with photography for a new book, The Outsider

New York-based photographer Elizabeth Heyert was well established in the commercial world before she began working on her own experimental fine art projects. Her unconventional, conceptual series depicting post mortem figures (The Travelers) and photographs taken through a one-way mirror (The Narcissists) could not be further from her glossy images for Vogue and Architectural Digest, and yet quickly gained her critical acclaim. For her latest series she travelled to Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Suzhou in China to examine people’s complex relationship with family legacy, posterity and amateur portraiture.

On a new form of portrait photography...

“I first went to China as a tourist in 2011. I had a big birthday and I thought ‘I’ve reached this great age so I have to go and see the Great Wall before I have to go there in a wheelchair!’ When I got there the project immediately came to mind, because I was struck by the masses of people. Everyone was taking normal tourist photographs, making a ‘V’ with their hands… but a lot of people were making very thoughtful portraits. They were choosing the environment carefully, with family members helping to direct and organise. I saw this happening over and over again and I started to think how unique this was, and so different from all the other tourist pictures I’ve seen.”

On being an outsider...

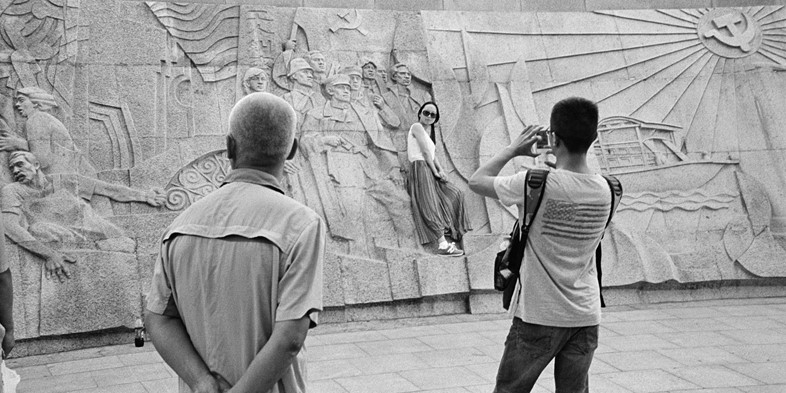

“In China I was immediately struck by how foreign I was. I travel all the time so I felt very comfortable as a tourist, but I knew that I had a ‘western’ view. I consider myself a portrait photographer and I’ve always hated that 19th century style, where people rich enough to have cameras would go to the East and set up Victorian tableaus just like they were in the West, and we think that’s how things were – but they weren’t real. I decided to go back and just watch the Chinese photographing each other and see what I could learn. Before you know it I was taking these portraits.

No one had any idea I was taking these pictures. I’m blonde and bear no physical resemblance to someone who is Chinese, so I was prepared to make gestures to ask if it was okay to take pictures, but nobody even noticed me. I felt like I was a ghost. I would work for eight hours at a time without speaking to anyone – actually I loved that. I think part of the reason is that everyone was so focused on what they were doing. I know what it’s like when I’m taking a portrait and I’m not interested in what is going on around me.”

On shooting with film...

“I didn’t use a digital camera; I used a traditional Leica. China reminded me of the 60s in the States, when everything was booming, when anything seemed possible. I’m not ignoring the repressive government or the human rights record, but when you’re there everything is new and there is opportunity and progress, even though of course not everyone gets to participate. I wanted to use a 60s style of street photography, with a Leica and a Tri-X film because it felt right for the time. I had to get in position; frame the shot; wait for the crowds to go and then manually focus and expose it. It was tremendous fun because it was a challenge, really going back to the old days. I was tapping into all these experiences before everything became so easy.”

On Chinese heritage...

“The only time people ever looked at me was when I sat on a bench to reload film; no one could work out what I was doing. They don’t even sell film in China anymore. One of my drivers told me that there is a museum in Shanghai where you can go and pay to play with an old-style camera and some film. Boy, does it make me feel ancient!

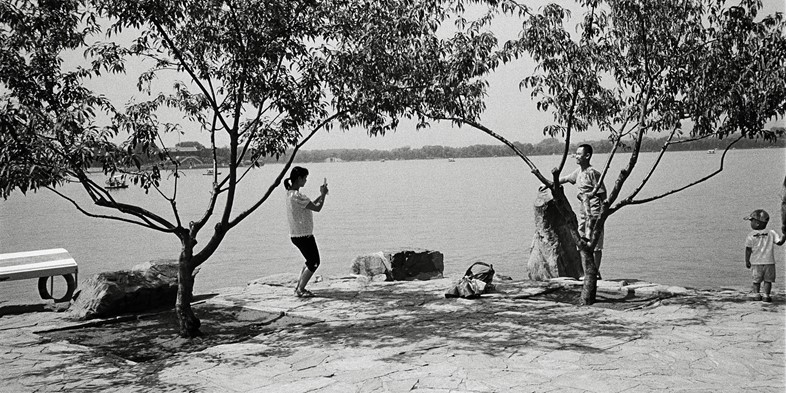

China has an interesting combination of correcting the past and moving away from it. It was only after I came back from my first trip and did some reading that I realised that there are no family albums, unless people hid or buried them. We all know what our grandparents look like but there’s something so strange in the fact that the Chinese don’t have that visual history. So now I think people find it really important to record these moments. They use the environment like a stage – finding rocks, and foliage and flowers. I went to a place called West Lake, outside of Hangzhou. It is a beautiful ancient area, which has a lot of spiritual associations; thousands of people go there. Another is a town called Suzhou, which has these fantastic, beautiful gardens.”

One Madeleine Thien’s short story...

“Some of the people I photographed have lived through [the revolution] and that’s one of the reasons I felt I couldn’t make authentic portraits one-on-one. I can’t imagine what it must have been like. I had the idea to have an original written piece in the book because I wanted somebody who really knew China to offer something from the inside. Madeleine Thien was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize a few years ago for Do Not Say We Have Nothing. I asked her to write about whatever she wanted. I sent her some of the photos but I said ‘it’s completely up to you’. She ended up writing this story that really puts you inside of that world. I was so thrilled that she didn’t just take the easy route and write an essay about modern China or photography.”

On reading relationships...

“Taking these photographs made me feel lonely because people seem to enjoy spending time with their families. They were lovely relationships and there was something so intimate about the way they photograph each other. However one of the things about being an outsider is that I made assumptions about certain things. There is an idyllic photograph of a young woman dangling her legs in the lake and there’s a man behind taking her picture. I think of that as a very romantic image, but the reality is that I don’t believe they knew each other – I think he snuck up on her.

There’s another picture like that where a woman is standing with her handbag and you see the hands of somebody taking a picture, but behind him there is someone peering over a rock, watching. I don’t know whether he was a friend or a peeping Tom. You just don’t know what’s happening, but that’s ok, because my role was just to watch them, and not to offer up my own clues. It is such an interesting way to approach portraiture.”

The Outsider by Elizabeth Heyert, with text by Madeleine Thien, is out now, published by Damiani.