Moominvalley is a fictional place, until you go there. Its other name is Finland, where, at several points during a trip arranged by the Dulwich Picture Gallery, I’m told that one of the defining traits of Finnish people is their preference for keeping their distance from most other people. In Helsinki, locals would rather wait 20 minutes for the next bus rather than risk brushing up against other passengers on a busy one. For Tove Jansson, the late beloved creator of the Moomins and fine artist in her own right, a desire to be apart meant spending entire summers in a wooden cabin on a rocky, remote outcrop; it also meant, as you discover when you trace the secret history of her life, an instinct to live by her own rules, from childhood to her death aged 86.

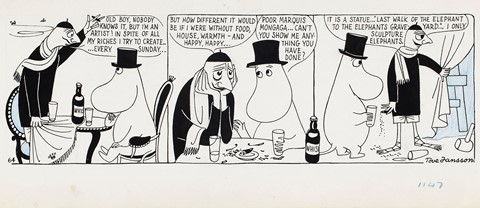

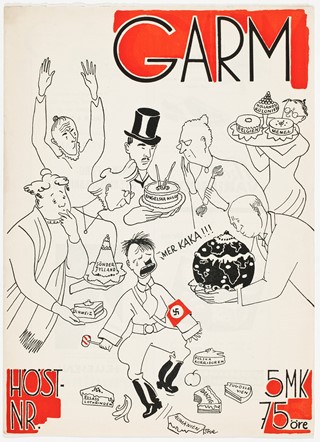

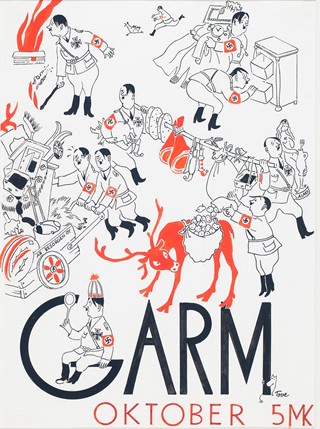

For most, Tove Jansson’s name is synonymous with the Moomins: the rotund, hippo-like creatures with a disarmingly existential philosophy, who first appeared on shelves in The Moomins and the Great Flood, published in 1945. By now, they’re a global phenomenon, having featured in nine books translated across the globe, their own comic strip in the London Evening Standard, a Japanese animated spin-off, and emblazoned on every product imaginable, from nail files to shampoos. But, as a new exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery hopes to prove, Jansson was also a fine artist worthy of a platform beyond Moominvalley. In fact, as the show demonstrates, she lent her idiosyncratic eye to impressionistic portraits, murals for restaurants and public spaces, and splashy, abstract worlds of colour on the canvas. It’s the self-portraits on show at Dulwich that seem to speak to Jansson’s pioneer spirit the most: there, the young artist emanates a very modern kind of strength, defiantly meeting our gaze above her cigarette smoke.

The facts of Jansson’s life can be traced in the Moomin stories, which mirror the darkness and joy of actual happenings. In Comet in Moominland (1946), the threat of total annihilation is in response to the dropping of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs; in Moominland Midwinter, Moomintroll’s new friendship with Too-tiki is based on Jansson meeting the woman who would become the love of her life, graphic designer Tuulikki Pietilä. But while Jansson undeniably invested much of her life in the Moomin novels, she continually returned to her love of painting. “I could vomit over Moomintroll,” she once wrote of the creature who would come to define her. “I shall never again be able to write about those happy idiots who forgive one another and never realise they’re being fooled.” If anything, Tove Jansson’s career may be an example of how your greatest passion may not be the thing you are in the end most recognised for. Besides, it’s in a place of slight discomfort where anyone finds the most creatively fulfilling spot; for Jansson, this wasn’t at home with the Moomins, but in the fear of not being taken seriously as a painter that always stayed with her.

From secret murals nestled above shopping malls to the neighbourhood archipelago shop where Jansson stocked up on cigarettes and coffee for the summer, Jansson’s creative inspirations can be felt in the places she frequented. As the artist wrote in her poetic memoir, The Summer Book (1972), “A person can find anything if he takes the time, that is, if he can afford to look. And while he’s looking, he’s free, and he finds things he never expected.” Jansson was ahead of her time precisely for how, as a woman, she prized her freedom and alone-ness; maybe that’s why going to the same places she has been feels so much like discovering secrets.

The Pink House, Helsinki

“Nobody has a round window like us,” said Tove Jansson of the home where she lived until the age of 15 or 16 with her family in Helsinki. An imposing, salmon-pink apartment block, it was here, on the very top floor, that Jansson began her passion for illustration. The Janssons were an artistic clan: her father was a notable sculptor whose creations you’ll find all over the city; her mother was a more direct influence, a successful illustrator who designed hundreds of postal stamp designs, and who, it seems, actually brought in most of the money for the family. Around the corner from the apartment, in one of Helsinki’s most popular squares, you’ll see a stone mermaid based on the young Tove herself, who often modelled for her father.

Summer House, Porvoo Archipelago

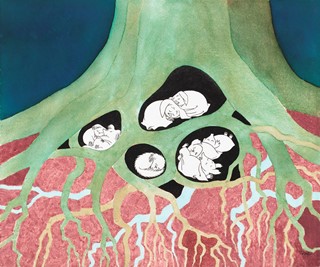

In the summers, the Janssons holidayed in a rented cottage east of Helsinki in the Pellinge islands, near the small city of Porvoo. Jansson would later say that her impulse for writing came from wanting “to write about things that scared her”; walking around the archipelago, it’s easy to see how Jansson’s experiences in nature would later create the world of the Moomin books. Beautiful but threatening, the stories’ landscape of rocky islands, caves, and seas that switch from calm to stormy in a second are direct descendents of Jansson’s childhood summers. The red clapper-board house where they spent most of their time is also rumoured to be the place where the first Moomin was born. As an adolescent, after a heated argument with her brother about the philosopher Kant, it is said Tove drew what would later become Moomintroll on the wall of the outhouse toilet, scrawling ‘Kant’ underneath; a thin, more unappealing creature than the cuddly troll we know today.

Tove Jansson’s Atelier, Helsinki

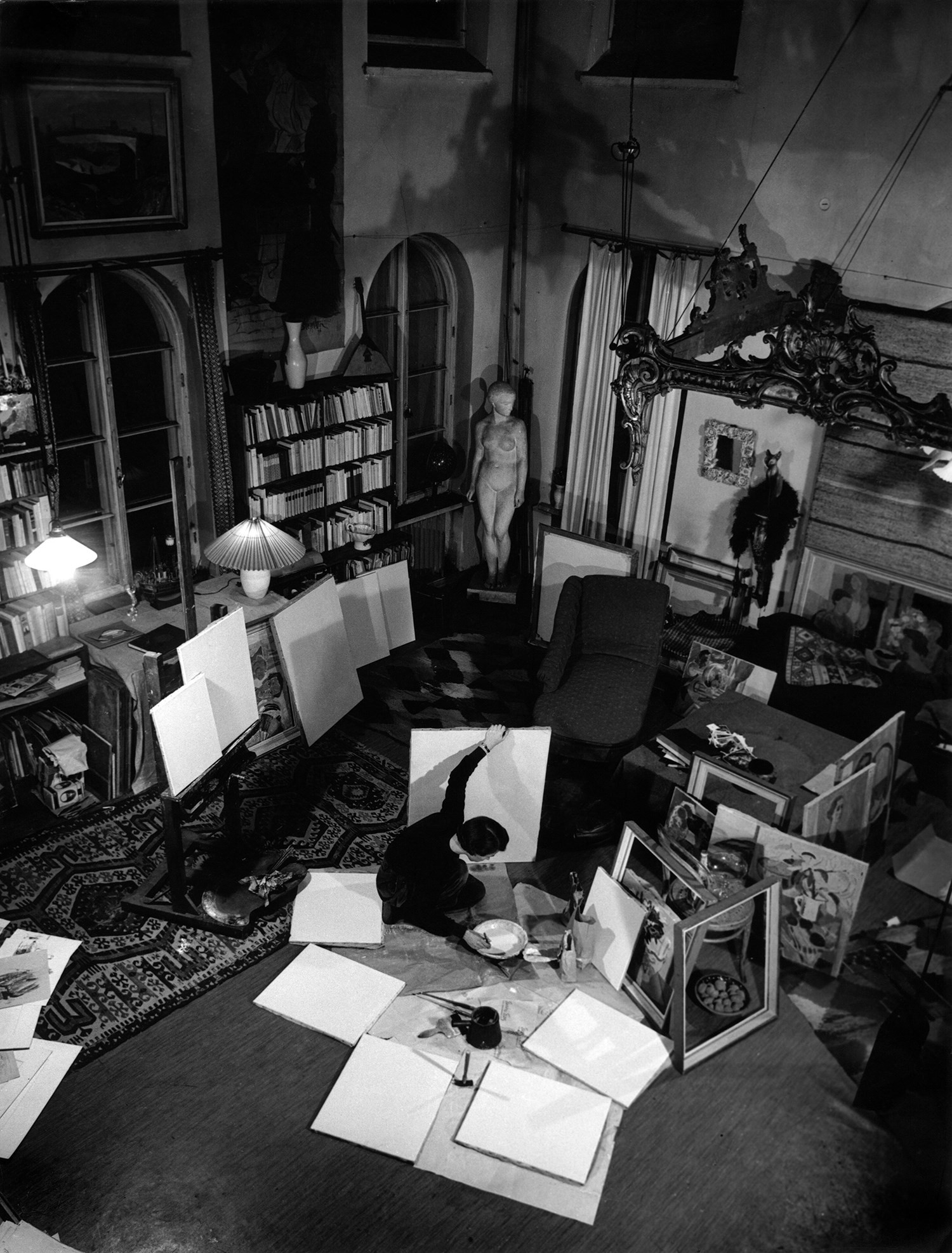

“It looks terrible after the bombings,” wrote Jansson of her new studio in 1945, where she lived and worked until the end of her life. “No windows, cracks everywhere, large pieces of the walls have collapsed, the stove and the radiators are destroyed. But it is still my great dream.” The building where Jansson had her studio from the spring of 1944 until the end of her life looks like any other unassuming, well-to-do apartment building in Helsinki – unremarkable, that is, except for the plaque emblazoned with a young Tove’s visage outside. Sophia Jansson, Tove’s niece, showed us round the atelier; a small, perfumed woman with a tight ponytail and Tove’s recognisably pointed features, she’s the current executor of the Moomins estate and looks after the apartment. A split-level attic apartment at the top of the building (you can just about see the sea from the highest window, important for Tove), the light and airy apartment feels like a dream for any artist. But it wasn’t always so ideal – with no heating, Sophia says, conditions were as low as -1 degrees in those early winters. After several renovations over the 57 years she occupied the space, it became what we see today.

Over two levels, the main room is filled with floor to ceiling bookshelves, sculptures by Tove’s dad, and a large canvas rack with countless paintings – many of which, Sophia says, remain failed experiments never seen outside of the apartment. Upstairs, the first sign of the Moomins; a bookshelf filled with Moomin books translated into Japanese, Urdu and countless other languages; that there is little trace of the Moomins on the whole might say something about Jansson’s desire to be taken seriously as a painter. The best part of the apartment might be the secret side room, a whitewashed space dedicated, as she wrote at the time, to “feminine knick-knacks, all my soft, playful, glossy and personal stuff”.

Murals Above Kamppi Shopping Mall

Transcending the escalators of a cinema and shopping centre complex in the middle of Helsinki might not seem the most direct route to Jansson’s life in 1940s Helsinki, but once you leave behind the smell of popcorn, you’ll find the Helsinki Art Museum (HAM for short) which houses secret murals by the artist. Dating from 1947, the two murals – Party in the City and Party in the Country were commissioned for the restaurant of the City Hall. In the former, you’ll find hints at Jansson’s own life at the time: a dark-haired figure on the dancefloor is her (secret) female lover, theatre director Vivica Bandler, while Jansson herself smokes a cigarette on the table, alone. Look even closer, and you’ll see small, barely perceptible Moomins poking their heads out among the action.

Village Shop, Pellingi Island

On Pellingi Island, you also find the Village Shop (Soderby Boden) a tiny, orange and white painted cabin where islanders have bought their supplies and sent their post for nearly 100 years. It’s here that Tove Jansson and Tuulikki Pietilä would buy their supplies for the summer months they spent at their home on the island of Klovhaven: bottles of water, due to the lack of running water at the cottage, but perhaps as importantly, coffee and cigarettes. When we visit, the shop contains the usual tinned goods, stationery and toiletries, but naturally there’s some Moomin-themed shampoo and sweets in the mix – and, strangely enough, a fruit slot machine.

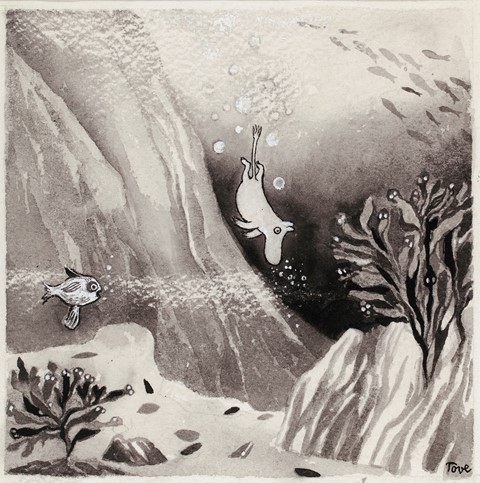

The House at Klovhaven (Well, Nearly)

Two bus journeys, one ferry passage, and an hour’s choppy boat ride from Helsinki later, you land at Jansson’s famous Klovhaven cottage; or in our case, not actually land on it, but rather see it from a safe distance, as sadly the winds didn’t allow us to get to the shore. Of all the islands in the archipelago, Klovhaven was not Jansson and Pietilä’s first choice to build on, but after a process in which every member of the community had to sign off their application (and the small matter of exploding a boulder in order to be able to build at all) the island was theirs. At only 25 square metres, the tiny cabin was a haven for a couple who cared little for material things, preferring the simple pleasures in life: swimming, smoking, painting and silence. Locally, Jansson and Pietilä were known as ‘the girls’; they would fight and make up over their months on the island, with Jansson reportedly throwing rocks into the sea when she got mad. But though Klovhaven couldn’t be harder to get to, ‘the girls’ weren’t always alone; somehow, Moomin fanatics would find their way there, and Jansson was invariably hospitable. The couple would even sleep in a tent when they had company, so that unexpected visitors could sleep indoors. When Jansson and Pietilä became too old to survive the harsh conditions on the island in 1992, they left it behind for good; according to the local captain who brought us there, ‘Tutti’ looked back, but Tove never did.

Tove Jansson (1914-2001) runs until January 28, 2018 at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London.