A new exhibition spotlights the iconic artist’s little-known photographic work, including some arresting examples of the first selfies in history

In iconic paintings like The Scream (1893), Edvard Munch expressed the anxiety and uncertainty of modern life. In addition to the psychologically charged paintings, woodblock prints and watercolours Munch is well known for, he also explored the medium of photography. Curious about contemporary technology, Munch purchased his first camera, a Kodak Bull’s Eye No. 2, in Berlin when he was 40 and began documenting his surroundings. As a new exhibition, The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography, at Scandinavia House reveals, Munch used the camera as an expressive tool. Much like his paintings – many of which can be seen in the parallel and complementary retrospective Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art – his photographs focused on making the invisible visible.

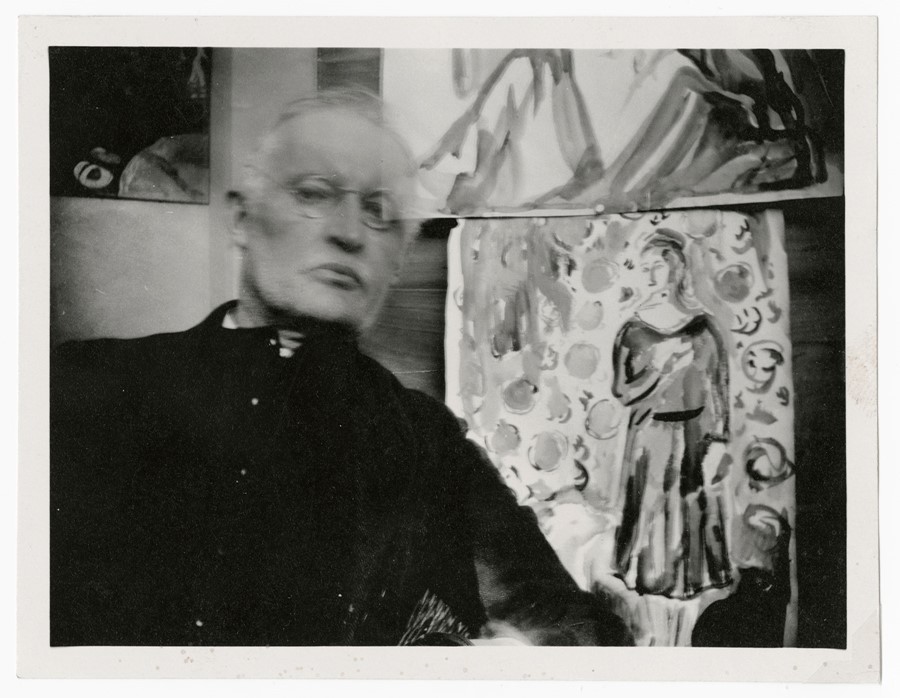

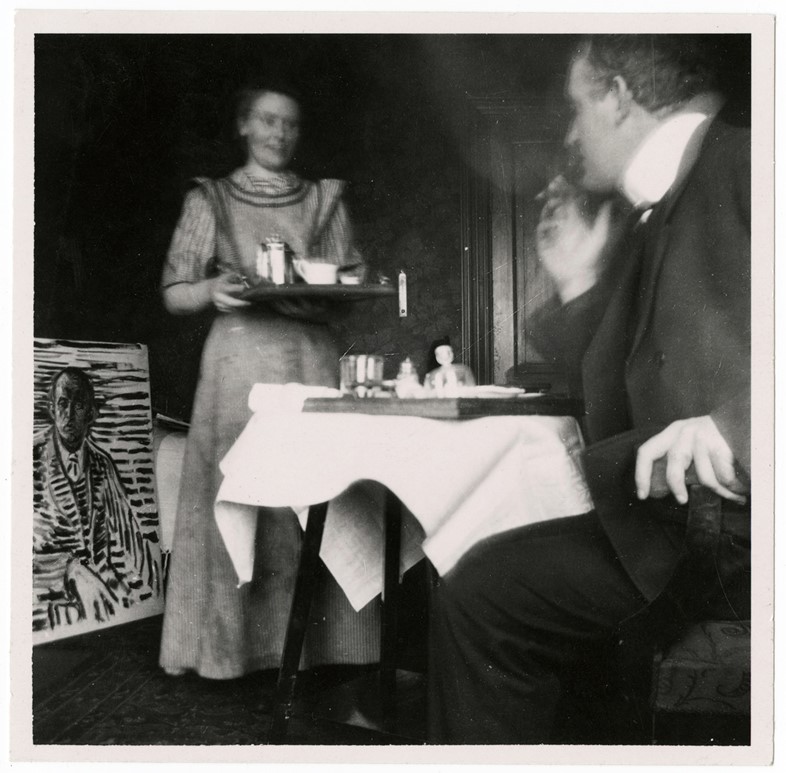

Munch mainly took self-portraits and portraits of family and friends with a strong narrative element, chronicling his lived experience. “To me, the photographs are very informal and sometimes extremely humorous explorations of the artist and his environment,” explains curator and art historian Dr. Patricia Berman. “He does to some extent document himself, his friends, his immediate environment – and in his brief film clips, environments in which he wandered – but he rarely does so straightforwardly.”

In Self-Portrait ‘á la Marat,’ Beside a Bathtub at Dr. Jacobson’s Clinic, Munch poses semi-nude in a room at Dr. Daniel Jacobson’s clinic in Copenhagen, where Munch admitted himself during a period of profound instability. Like many of his other self-portraits taken at close range, this image might be one of the earliest selfies ever taken – Munch often held the camera at arms-length so he could press down the shutter button.

Before taking this image, Munch had already created two paintings about the death of French revolutionary Jean Paul Marat, who was murdered in 1793 by Charlotte Corday while lying in a bathtub. In 1902 Munch had a terrible fight with his then-lover Tulla Larsen, a struggle in which one of his fingers was mutilated by an accidental gunshot. This episode became a longstanding trauma for Munch and he identified with Marat as a kind of martyr figure. There’s an element of exaggeration there, but the photograph captures a sincerity. “What I find so poignant in his images of himself at the clinic, and particularly this one, is his extreme vulnerability,” Berman notes. “I see these photographs as highly intimate pockets of contemplation, and perhaps little screens for his later reflections on this period of convalescence.”

Munch was interested in the potential of photographic “mistakes”. He used the visual effects of motion, double exposures and distorted perspectives to create poetic images in which the everyday becomes something other. It’s not a coincidence that Munch’s interest in photography coincided with the rise of spirit photography in popular culture and the invention of the x-ray. “As a highly attuned consumer of visual imagery, and himself the owner of an x-ray of his hand, Munch may surely have thought about how the photograph – supposedly the great medium of material evidence – could allow for the invisible to be manifest,” Berman says. “I also see the blurring as a way for the artist to explore time, as though he was on a different plane from his surroundings... I believe it is the fascination with this process of rupture that was interesting to him.”

The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography runs at Scandinavia House in New York until March 5, 2018.