A new exhibition at New York’s Met shines a long overdue light on the legacy of Baron Adolf de Meyer

Who? No really, who was Baron Adolf de Meyer? During his lifetime, he adopted a number of identities – pioneering photographer, aristocrat, blue haired renegade, celebrity portraitist, Vogue favourite, astrology obsessive – but now a new exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art is attempting to pin him down.

Born probably in 1868 and possibly in Paris – but maybe Vienna or Helsinki – to a Scottish mother and German-Jewish father, De Meyer landed in London in 1895 bearing a Baronial title of uncertain provenance. Despite living in an era ablaze with anti-Semitism and homophobia, epitomised by the Dreyfus affair and the Wilde trial, the flamboyant De Meyer flourished in England. He gained entry into the glittering coterie of upper-class patrons and artists who surrounded Edward, Prince of Wales, and in 1899 he married Olga Caracciolo, an Italian noblewoman widely believed to be the Prince’s illegitimate daughter. Their marriage was one of convenience – both were gay – but together the couple cemented each other’s social status. An artist’s model beloved by Whistler, Singer Sargeant and Sickert, Olga became her husband’s frequent subject, while it was among the throngs at their extravagant parties that De Meyer found his most influential fans and muses – photographer Alfred Stieglitz, Nijinsky of the Ballet Russes, and “the most scandalous woman in Europe” Marchesa Luisa Casati.

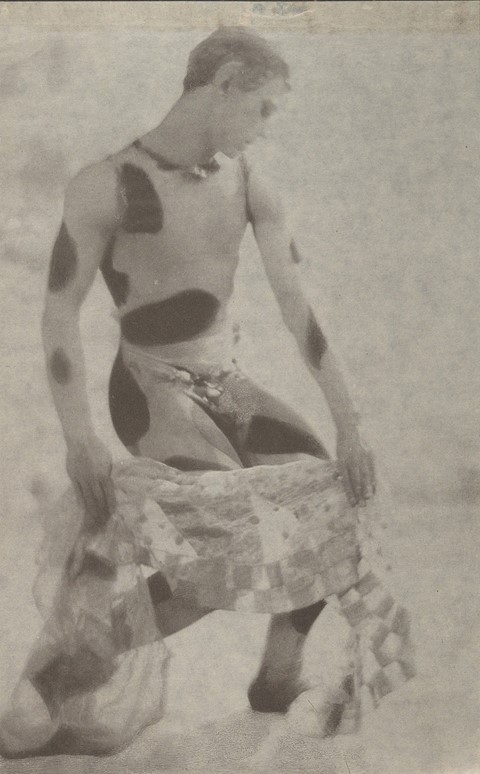

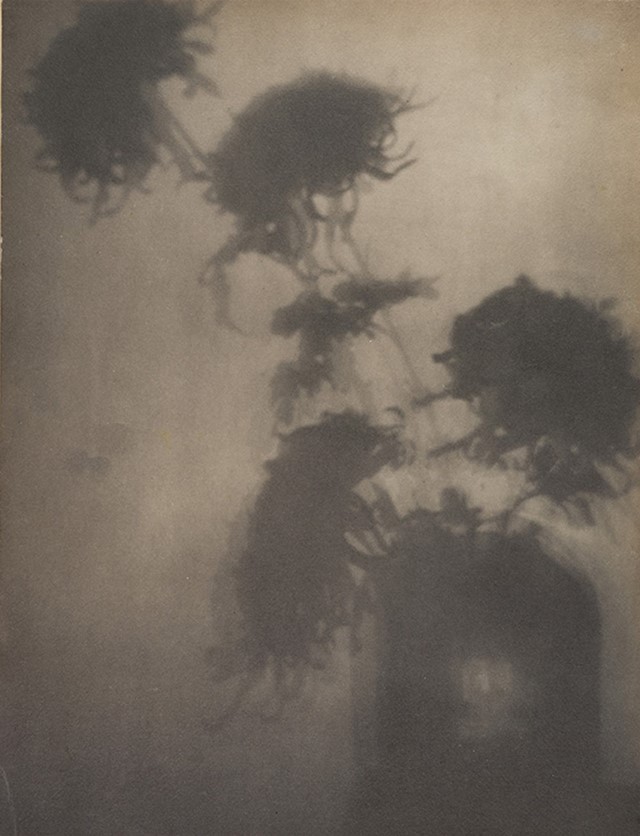

What? In tune with the era’s Pictorialist movement, De Meyer created romantic, aesthetic images that elevated reality into fantasy. Described by Cecil Beaton as the “Debussy of the camera”, his images shunned strict realism, instead emphasising emotion to painterly effect. His portraits were dramatic and intense, demonstrating his talent for making clothes look sublime. Pioneering the use of artificial light, mirrors, reflectors and a Pinkerton-Smith camera lens to create fantasy settings for his sitters, De Meyer was at the forefront of a new visual vocabulary for fashion photography, one with a direct link to the likes of Deborah Turbeville and Tim Walker today.

Edward VII’s death in 1910, followed four years later by the declaration of war, demoted the De Meyers from London society favourites to suspected German spies. In 1914, on the advice of an astrologer, the couple moved to New York where De Meyer began working for Vogue. Here his aesthetic vision came into its own, enchanting not only readers and editors, but advertisers who recognised the value of having their clothes and objects so enticingly depicted using De Meyer’s tricks of the light. These were the early days of consumerism as fantasy. In De Meyer’s society portraits and fashion essays, Rita Lydig, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Gloria Swanson, Dolores and the Ziegfeld Follies girls were transformed into mysterious, ethereal figures, their sumptuous gowns available to buy on 5th Avenue.

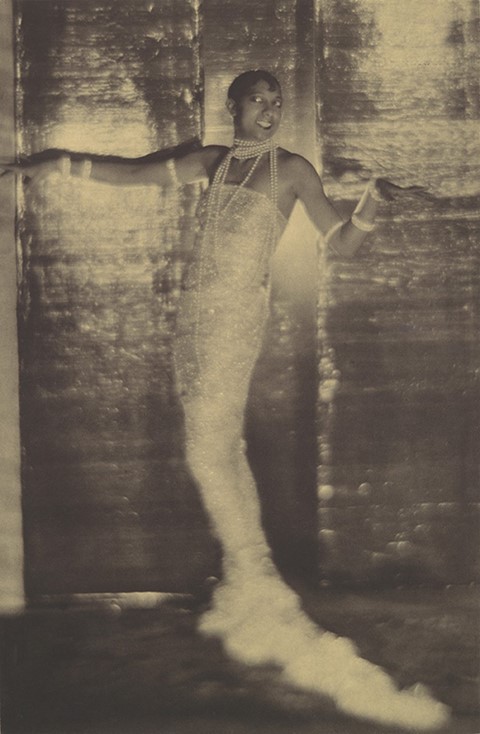

Why? In 1922, his name now made, De Meyer moved back to Europe to become Harper’s Bazaar’s chief photographer in Paris. He was replaced at Vogue with the minimalist Edward Steichen, who was reportedly staggered by the piles of technical equipment his predecessor left behind. This would mark the end of the trend for soft focus excess at Vogue, with Steichen ushering in Modernism’s hard edges. But as the engines sped up on the Roaring 1920s, De Meyer’s fantasy visions were still very much in demand. He shot the singer Josephine Baker – a vision in sequins and feathers – and Coco Chanel, in a fur lined suit of her own making, and brands such as Elizabeth Arden were clamouring for his otherworldly touch on their ads.

However, it’s unclear how enamoured De Meyer was with his commercial success. In a letter to Alfred Stieglitz, he fretted that he had betrayed his art by being paid for it, to which Stieglitz replied, “No, you have not prostituted photography”. In the 1930s, he destroyed many of his works, and attempted to shift gears into the style of his younger rivals. It was a failure, and his popularity dwindled, obliterated by the crisp clarity of Man Ray and Cecil Beaton. He died in Los Angeles, largely forgotten, in 1946.

In Quicksilver Brilliance the Met has united 40 rarely seen works from its archive, including still lifes, travel snapshots, portraits of his wife Olga, Baker and Lady Ottoline Morrell and a rare copy of the “luxuriously queer” album he created of the Ballet Russes’ L’Apres Midi d’une Faune in 1912. While we may not be entirely sure who Adolf de Meyer was, and the artist himself may have had doubts, his works tell the story of a visionary who wrought fashion as fantasy, light as paint and artifice as dreamy unreality.

Quicksilver Brilliance: Adolf de Meyer Photographs runs from December 4, 2017 until March 18, 2018 at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.