A new exhibition at Tate St Ives explores the Modernist literary icon’s lasting effect on female artists from the past 100 years

The prevailing power and remarkable legacy of Virginia Woolf’s writing serves as inspiration for a new exhibition at Tate St Ives, where over 80 female artists practising from 1850 to the present day have been brought together. Spanning Woolf’s contemporaries, those who cite her directly and others who embody the principles and ideas behind her writing, the exhibition consists of everything from painting, sculpture and printmaking to video and performance and covers distinct themes of landscape, domestic interiors and the presentation of the self, all of which were fundamental to Woolf’s practice. Here are some of the highlights.

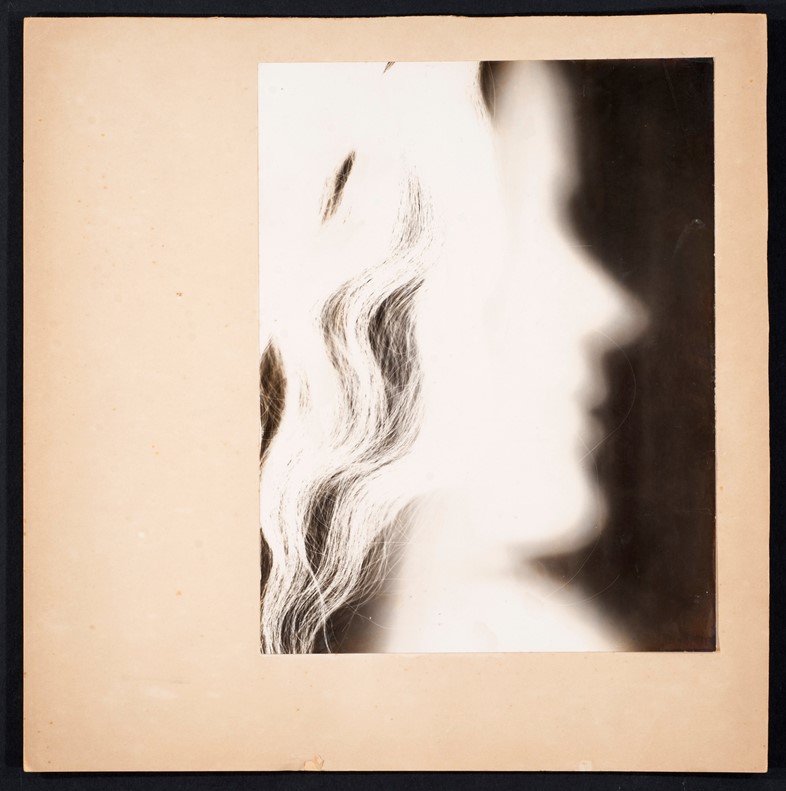

1. Self-Photogram by Barbara Hepworth, 1933 (above)

The definitive St Ives artist is best-known for her bold, enigmatic sculptures that relay the power of the Cornish landscape and strike an exceptional balance between positive and negative space. In this photogram (a term used to describe images created by exposing directly on photographic paper, as opposed to using a camera) Hepworth experiments with new forms of visual perception. Her interest in the process came about after she struck up a friendship with László Moholy-Nagy, the influential constructivist who taught at the Bauhaus and pioneered the self-portrait process.

2. 10 Days – 100 Photos by Birgit Jürgenssen, 1980-1

This foreboding altarpiece consists of 100 performative polaroids that question the presentation of the female body. “The identity of the woman has been made to disappear – all except for the fetishised object, which is the focus of male fantasy,” says Jürgenssen. The images depict singular limbs, strange staged and sexualised portraits and a collection of thinly censored breasts. The distinct layout of these images recalls a religious or ceremonial events, as if this faceless woman is being offered up as a form of sacrifice.

3. Spanish Landscape with Mountains by Dora Carrington, c. 1924

This surreal landscape depicts the intense heat of Andalusia, complete with ragged aloe vera that seems to dwarf the diminutive travellers that snake along the hillside. Carrington’s complete disregard for rules of perspective give this painting an uneasy but nevertheless compelling quality, as you search for more signs of life in the rippling mountains below. Of course, the main focus of the piece lies in the two soft peaks that hold more than a passing resemblance to a pair of breasts. This obvious nod combines surrealist sensibilities with a fresh Modernist style that conveys the vastness of the Spanish countryside.

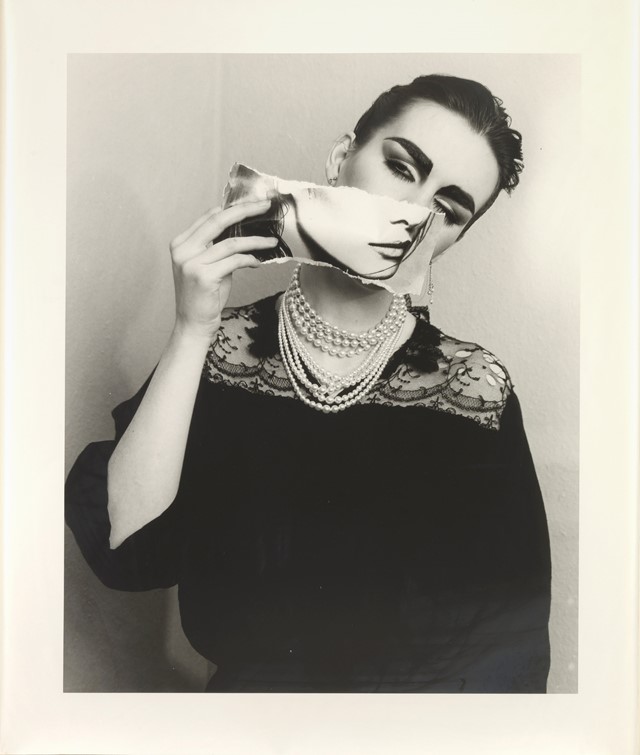

4. She/She by Linder, 1981

Punk collagist Linder is perhaps best known for her graphic commissions, including the Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict record cover, but her investigative practice into pop culture imagery also extends beyond the exacting cut-and-stick process. She/She features fourteen black-and-white photographs, some featuring Linder’s own text taken from a cassette released by the post-punk group Ludus (she was a member). The others feature the artist, heavily made up with thick New Romantic eyebrows, as she creates ‘self-montages’ that reimagine parts of her face with pages from a fashion magazine, or manipulates it with various materials. The process breaks down notions of the feminist ideal, while remaining sexually powerful.

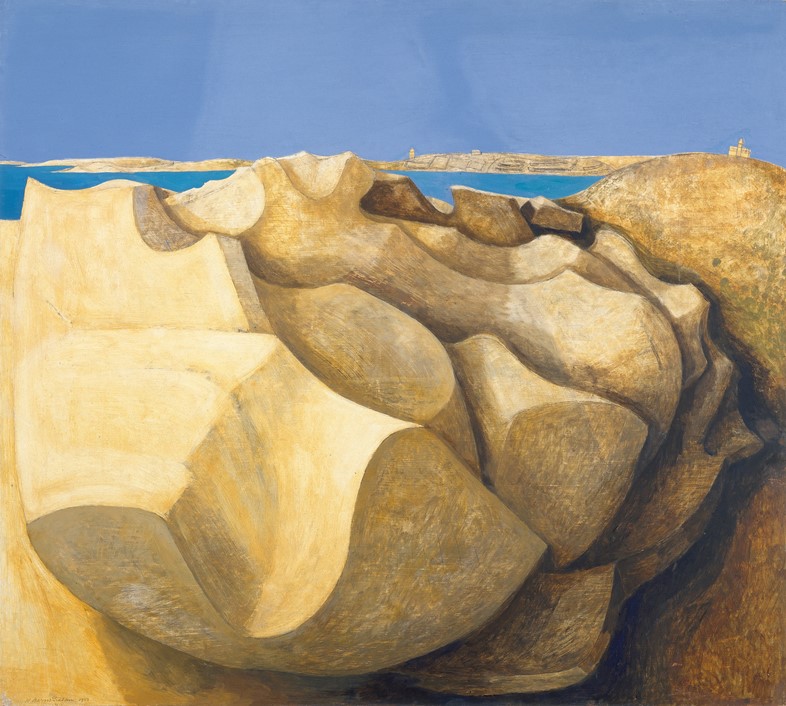

5. Rocks, St Mary’s, Scilly Isles by Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, 1953

This bizarre natural rock formation seems to push against the canvas, as if the painting cannot hold the weight or mass of such an object. Barns-Graham had a preoccupation with geological formations, which was inspired by a trip to Switzerland, where she was struck with the simultaneous solidity and transparency of the Grindewald glaciers. As a result, she began depicting objects ‘in total view’, as if every aspect can be seen on one picture plane. In this unorthodox landscape priority is given over the examining this enormous rock, while the sky and sea become superfluous.

6. Cactus by Laura Knight, c. 1939

Better known for her portraits and broad landscapes, Laura Knight’s somewhat jarring image of a cactus presented against the backdrop of a frosty British landscape appears startlingly modern. The unusual pairing of a tropical plant with barren cold, and the depressing depiction of a handful of dead flies, is a far cry from the more familiar setup of a sunny window view. There is something distinctly cold and cruel about the piece, and the unusual aspect of the window pane forces us to imagine what is going on beyond the edges of this painting.

7. Collapsing New People by France-Lise McGurn, 2017

Tate St Ives’ current artist in residence McGurn has been given free reign over the gallery’s stairwell as well as presenting a new painting and wall motif in the exhibition itself. Her colourful, delicate line work focuses on throngs of women partaking in various activities, in a joyous and dreamlike jumble. Her canvas piece is titled Your daughter’s daughter, alluding directly to Virginia Woolf’s notion that “we think back through our mothers”.

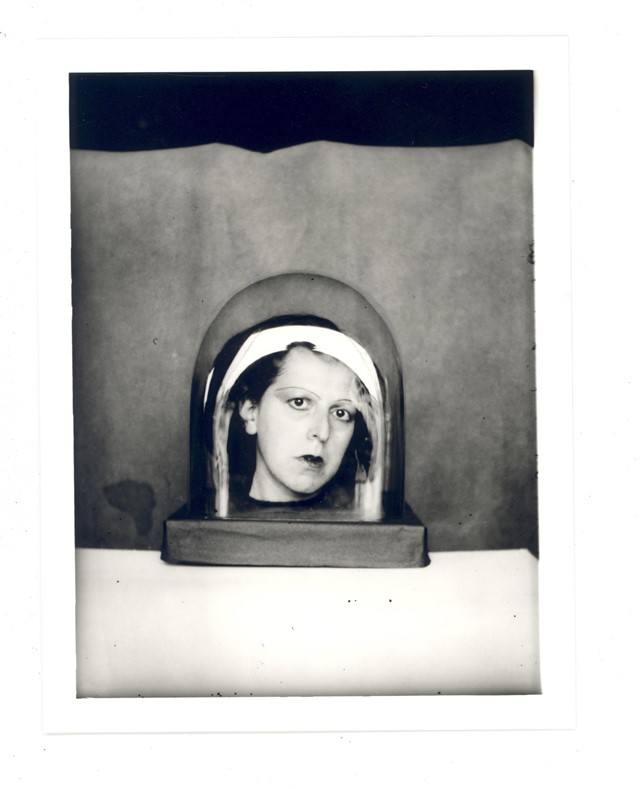

8. Studies for a Keepsake by Claude Cahun, 1925-6

Claude Cahun’s subversive photographs investigated androgyny and self-image years before the term ‘gender fluidity’ was coined. Recently her work has been reappraised, not least in a recent duo show with Gillian Wearing, where the influence of her experimentation with masks and costuming has an obvious connection. In this striking self-portrait, she appears to have completely detached her head and the playful reflections encase her two-fold beneath the glass. Her startling stare and theatrical makeup allude to vaudeville or even a horror show, as if this delicate face has just been picked up off of a shelf.

Virginia Woolf: An Exhibition Inspired by her Writings is at Tate St Ives until April 29, 2018.