Dividing her defiant works between three prestigious London institutions, the visual artist talks us through her process

“The exhibition is just about pleasure – please enjoy it,” said visual artist Tacita Dean at the unveiling of her exhibition, STILL LIFE, at the National Gallery. She was a little out of breath, having opened another show space, PORTRAIT, only 30 minutes prior, around the corner at the National Portrait Gallery. These two shows, opening today, form two thirds of Dean’s record-breaking exhibition triptych, the third installation of which, LANDSCAPE, opens in July at the Royal Academy. Just as these three galleries have never worked together so closely, the decorated Dean – the YBA has both acronyms OBE and RA after her name – has never split her work into such rigid categories. Catching up with the artist at her trailblazing new shows, she explained how she both evaded, and enjoyed, these new categories.

Starting in the main room at the National Portrait Gallery, Dean unveiled numerous unseen films: portraits of artists in their studios, environments and homes. Behind her podium a charming and close-cropped film of David Hockney smoking in his studio played on a loop, his laughter cutting through the various speeches. Other artists captured in situ – Cy Twombly, Claes Oldenburg, Mario Merz – each an elegant meditation on their practice, populating the sprawling hall. “I didn’t even think these were portraits,” Dean explained of how she instead thought of them simply as films.

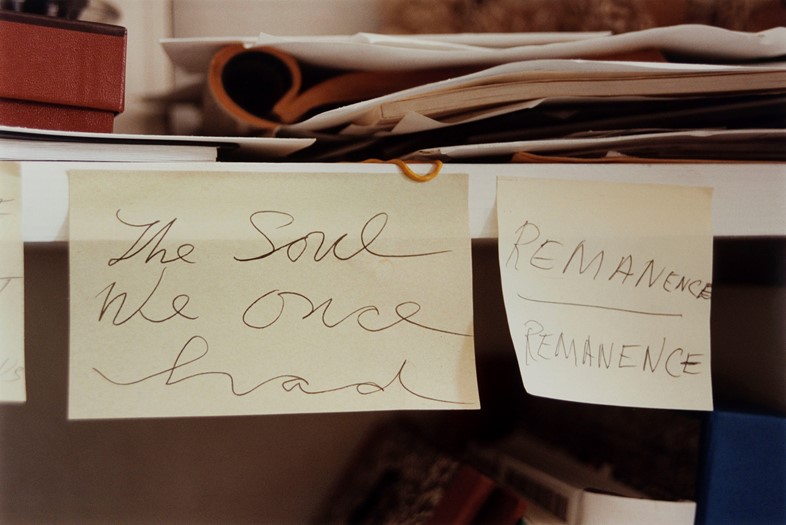

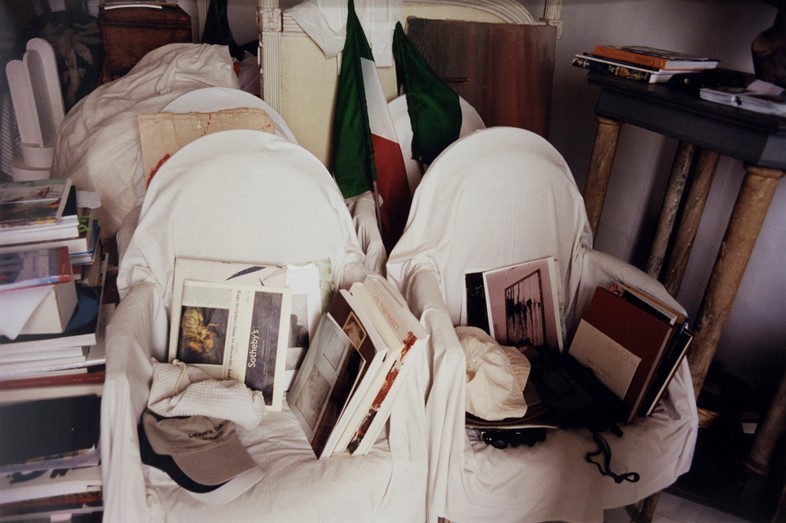

And it makes sense: in much of the footage, the artist is obscured. In Edwin Parker (Cy Twombly’s given name), two short continuous-loop silent films, Twombly is invariably hidden. He is spied through blinds or seated behind sculptures; an assistant busies himself around a mounted work. What emerges is a sense of place, a meditation on process. “Artists do interest me,” she admits. “The process interests me, you know, the internal thought interests me, thinking interests me.” The portrait of Twombly’s process is fleshed out by photographs lining the hall that comprise GAETA, fifty photographs plus one. Fifty of these photos offer vignettes of Twombly’s studio space: scribbled Post-its, statuettes, shelves stacked with portfolios, sketchbooks and drawings – his trademark colourful dribbles spill across unbleached papers. There’s a 51st, not labelled, taken in Italian still life painter Giorgio Morandi’s studio – “an homage to Cy in relation to Morandi and vice-versa”. They are still life photographs, but portraits too.

There are no ‘traditional’ portraits on show – no head and shoulder paintings or photographs. And apart from Cy Twombly’s studio ephemera, very few static images at all. Film, specifically that of the photochemically exposed moving image, is Dean’s medium of choice. “When I started at art school, it was just the normal moving image medium but then I had to resolutely stick to it because there is a bearing of time, for me, that is embedded in actual film – its internal disciplines. Not to mention how beautiful it is as a visual art form... it has what I call ‘medium resistance’ since it’s always going to run out in four minutes, or ten minutes. It brings in the idea of editing: how to get around problems of not having a permanent version of something. So I use those disciplines very proactively in terms of making my work, and editing.”

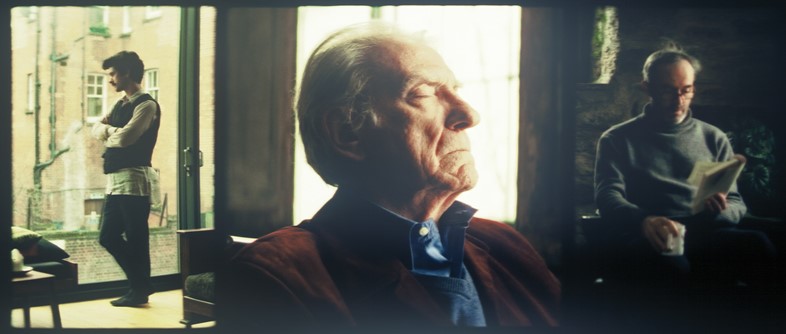

The most extraordinary example of her play on these disciplines can be found upstairs in the portrait gallery. It’s a small room curated by Dean and hosting just a handful of the gallery’s own Elizabethan and Jacobean portrait miniatures – the pocket-sized artworks popular in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Dean’s own miniatures sit centre stage, projected on to the wall about 15cm wide. One film, His Picture in Little, depicts three generations of Hamlet-playing actors – Stephen Dillane, David Warner and Ben Whishaw – in an impossible dialogue together.

The piece takes its name from a line in Shakespeare’s Hamlet, in which portraits including miniatures were a symbolic part. Dean created a stencil that, in covering the aperture, allowed the artist to capture all three actors in the same photochemical film frame without them ever meeting. Head and shoulder shots, as well as fully reclined poses, are intercut with whirling magnolia trees and quivering snowdrops. “So I filmed Steven on the left, rewound the film, Ben in the middle, rewound the film… then filmed David Warner on the right… at different times, in different countries. And then only at the very end does the film get processed and then I see what comes out. What happens is this magical moment which is all about the coincidence of gesture: Ben might turn left and Steven turn right – it’s all just unknowable.”

Such magic was magnified in Providence, the second film running on that projected screen. This latter portrait showed David Warner again, this time interacting with a hummingbird that would later be spliced onto the film next to him. “It turns out that he has a love of hummingbirds – I said, ‘David, just imagine you’re going to be next to a hummingbird’. He gave this exquisite performance to the hummingbird that didn’t exist, on side of the screen. I took this half-exposed roll of film to Pasadena, Los Angeles, in Huntington Gardens and… well they’re not very easy! But I got them, thank god. But in his performance, the birds are in his head, his imagination. It’s beautiful what happens between David and the bird.”

From imaginary birds to the feathered creatures at Dean’s STILL LIFE show across the way. “This is a wall of birds: one tethered, one stuffed, one missing, one dead, one alive,” she pointed, inside the second room she’d curated where a selection of still life paintings and photographs are pleasingly paired in a manner that challenges both their surroundings, and their contexts. Here Bread, a Twombly work, is sandwiched between a Chardin imitator’s Still Life with Bottle, Glass and Loaf and Roland de la Porte’s Still Life with Bread and Wine – the sparseness of Twombly’s crust perched upon a bistro glass undoing the gravitas of those lavish oil paintings of domestic scenes.

As with her films, Dean’s splicing of time frames comes into play here too. Having asked her contemporaries to contribute, she pooled works from current artists like Thomas Demand and Wolfgang Tillmans alongside works from the gallery and beyond. Tillmans offered Beerenstilleben, his sunlit still life of empty berry punnets, with a caveat coupling: “I asked him what he’d like to offer and he said: ‘It’s the berries, but it has to go next to the Zurbarán.’” And so Tillmans’ loose arrangement – debris of daily life, discarded and captured in situ – sits beside Francisco de Zurbarán’s careful oil painting, A Cup of Water and a Rose. A dialogue plays off between them with each picture inflecting its own qualities upon the other: Zurbarán’s seems more still and desolate in the wake of Tillmans; Tillman’s more elegantly arranged.

Dean’s filmed still life works make up her own offering to the selection and being film, their very nature confronts the parameters of the genre and its implied stillness. In Prisoner Pair, an almost abstract scene shows two pears rolling around in a glass of schnapps – magnified and moving, they evade the detailed study typically offered by the meditative medium. In Idea for Sculpture in a Setting, grainy black and white film pans in, out and across a tree trunk in a landscape. “I collect stones – I’ve collected stones for my whole life,” explains Dean. “I collect round stones. I collected flints. So it was wonderful to go be able to go and film one of Henry Moore’s flints. Not only film it inside... but in the landscape. But it’s not only in a landscape, it’s in Moore’s back field with his sheep roaming around, and what happens to an object when you put it into landscape? Because it’s still a still life. And I love the idea of still life in the landscape; that’s a sub-genre of mine.”

Pushing at the boundaries of genre in the hallowed halls of three of London’s most revered institutions, Dean is breaking ground in myriad directions. How her new and unseen films reshape our understandings of art at the upcoming LANDSCAPE will no doubt be a joy to behold too.

PORTRAIT at National Portrait Gallery, London, and STILL LIFE at National Gallery, London, run until May 28, 2018.