We speak to Clementine Keith-Roach, whose nipple vases are on show in London now, about anthropomorphising pottery to explore the female identity

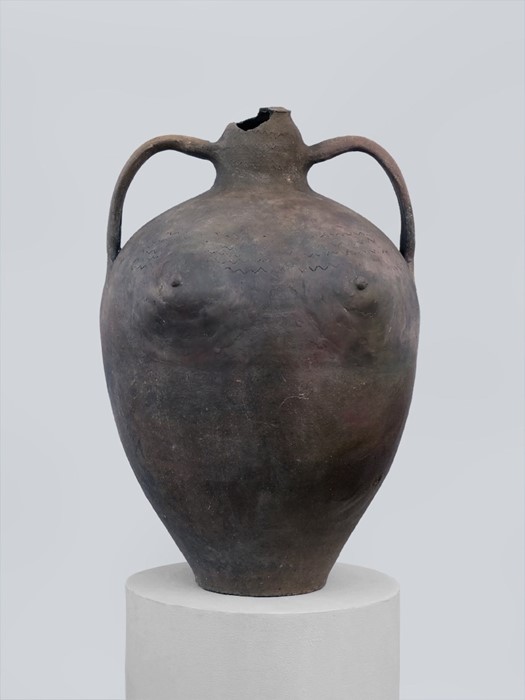

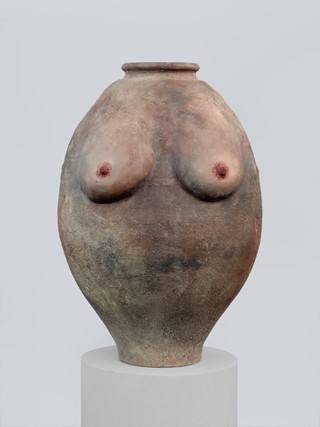

It was while living in Athens that Clementine Keith-Roach, having explored the city’s ceramics and artefacts, discovered a “particularly beautiful, bulbous vase” whose undulating form – emphasised by a narrow neck and base – reminded her of a bosom. The vase had “little clay pinches which clearly denoted nipples, and just by those small pinches, was totally transformed into a female body,” Keith-Roach explains. This idea of a pot taking on a human quality – the anthropomorphisation and zoomorphisation of ceramics was something she encountered often in Athens – stuck with the artist and set designer, and she began seeking out vessels which “felt bodily”, taking to “thinking about the surface of the pot as skin and wanting to see what happened when I actually extended that surface into a more bodily, real shape”. After experimenting with affixing nipples rendered in clay to the pots, Keith-Roach turned to plaster casting, and made moulds from both her own breasts and those of women close to her which she then transferred to the vessels.

The resulting nipple vases are a study of the female body unlike any other: the surface of the pottery – which, aside from the breasts built onto it by the artist, is untouched – takes on its own skin tone and resembles a torso while remaining distinctly inanimate. Keith-Roach produces a mingling of spheres, as the domestic, corporeal, decorative, historical and functional are brought together through her found and altered pots – pots that “have a particular patina to them,” the sculptor explains, which she works over the top of to “bring out these human forms”. A reimagining of an ancient form (the Cycladic pieces encountered in Athens date back more than 2,000 years), these tactile, sensuous vases are both a celebration of and a means of connecting with the female form, and simultaneously of breathing new life into storied domestic objects.

Keith-Roach’s nipple vases are currently on show at Grace Belgravia, London, as part of Ladies’ Paradise, a group exhibition curated by Huma Kabakci and Nadja Romain and organised by Open Space Contemporary and Everything I Want, which showcases the work of four female artists working across painting and sculpture. (Some pieces are also featured in Hunter Whitfield’s Interiority, a show which Keith-Roach herself curated.) Ladies’ Paradise ruminates on women’s bodies in art on both a personal and societal level, and creates new dialogues on the subject by bringing the work of the contemporary artists together. Here, Keith-Roach expands on the process of plaster-casting, the periods of art history she feels an affinity with, and how becoming a mother affected her practice.

On the relationship between form and function…

“I’ve been particularly interested in the domestic object as one which has a clear function but often exceeds that function through its aesthetic qualities – which can also become symbolic qualities – and how these objects become psychologically charged within our life. I suppose my approach to making art at the moment seems to be taking these domestic objects as a starting point and trying to bring out their strangeness. This series of work really started in Athens, where I was living for a year and a half, and I would visit the museums, sacred sites and archaeological sites, and I was particularly attracted to the ceramics and the homeware over everything else. It felt like those things had a sort of modesty to them, but also were incredibly powerful, as their function was so clear and connected you to their past owners, but also they had these kind of ritualistic qualities to them. I’m interested in the Greek shaped pots: there are all sort of storage jars, amphoras for wine, or the larger ones are olive or olive oil storage jars.”

On the presence of nipples in art…

“Another thing I noticed is that the nipple has rarely been rendered as an actual organ in sculpture. You see it suggested, especially in Greek sculpture or even later, or you see it under fabric. Its shape is there but actually, quite rarely do you see it in fine detail.”

On the process of casting breasts…

“Casting is so wonderful because it really brings out all of the detail of the skin. I’m particularly interested in this at the moment because I’ve recently become a mother, so I’ve been making the pots whilst being pregnant and whilst breastfeeding. I began by casting my own breasts because I was so horrified by the transformation they were going through but, you know, they change. My body became like a machine and it’s very strange how separate you feel from it. Suddenly, its true function takes over and you’re just kind of hosting these breasts which are going through extreme transformations and also really changing week by week to the needs of the baby – so that was another thing that I think played a big role in the making of these pots.

“After a while I wanted to cast other women’s breasts because I think the kind of intensity and emotion and physical change that you go through felt too much for me to be using my own body at this point. It was nice being able to experience my own body in this way, and then to be able to use the bodies of women I’m close to, friends and my family for the pots, so it’s kind of an externalised interest.”

On finding the right pot...

“I find I have a kind of library of breasts and when I find the right pot, I find the right breasts that would suit that pot, and I sculpt them onto the pot and paint onto the breasts to, hopefully, seamlessly blend the patina of the pot to the breasts, to the body parts. The pots really become themselves. Half the work is finding the right pot and finding something that you feel like a body will grow out of it.”

On finding inspiration in the past…

“I suppose one of the reasons for moving to Athens was because I had a particular interest in archaic Greek forms and architecture and these sacred sites all over Greece. But definitely in my work, you see an interest in the way that the museum isolates these ancient forms and turns them into, in our eyes, sculptures, whereas actually they were objects that served particular functions.

“I’m interested in the way that forms reappear throughout history and are reworked in different periods in history and I suppose I see myself as a continuation of that, in some way. Surrealism is a more recent and important art historical moment for me, because artists were unlocking the psychic charge of everyday objects; they were taking these quotidian things and making them strange, which definitely relates to my work and my thinking at the moment.”

Ladies’ Paradise is on show at Grace Belgravia, London, until April 8, 2018, and Interiority is at Hunter Whitfield, London, until April 15, 2018.