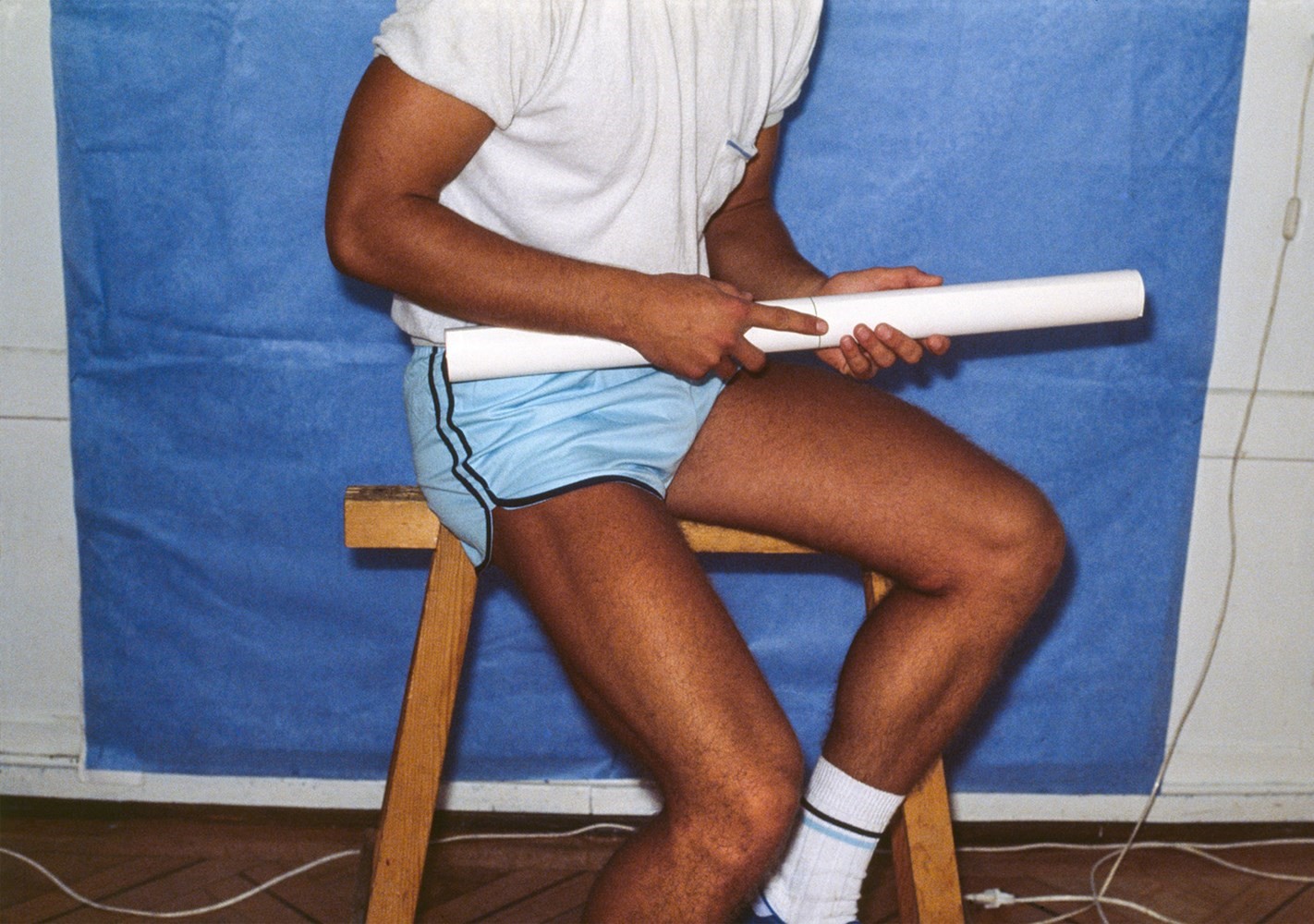

Walter Pfeiffer is a single-shot photographer whenever possible. “One click, and that’s it,” he tells me at the opening of Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins at London’s Barbican, gesturing towards his now iconic 1974 photograph of a boy squeezing toothpaste onto a brush, which is blown up on the wall next to us. “It’s only one – not 10 or 15 times, even when I work for magazines.”

His instantaneous way of working came about partly due to practical limitations when he was first starting out. “We had no money for film, so we had to work in a concentrated way,” he explains – but it also lent itself to the intimate community he has spent his career thus far documenting; friends and friends of friends came to be captured in his Zurich home with his small Polaroid camera. “I’m not a reporter of outside life. It has to be staged in a way,” he says – and indeed, there’s a warmth and a subjectivity to his work, especially when it is juxtaposed against a wealth of documentary photography, as it is in this exhibition. This is partly because Pfeiffer was so familiar with his subjects: “there were some people I saw who came to be photographed, and then they brought friends – it was like a snowball effect until there were more and more.” Now seen with the benefit of hindsight, this community of artists and friends with whom he subverted established ideas about gender and identity feel like a collective of lost souls, preserved on photographic paper. “It was their energy and character, the beauty of them that I was drawn to,” he says, somewhat wistfully. “Some are gone now, and some are still living.”

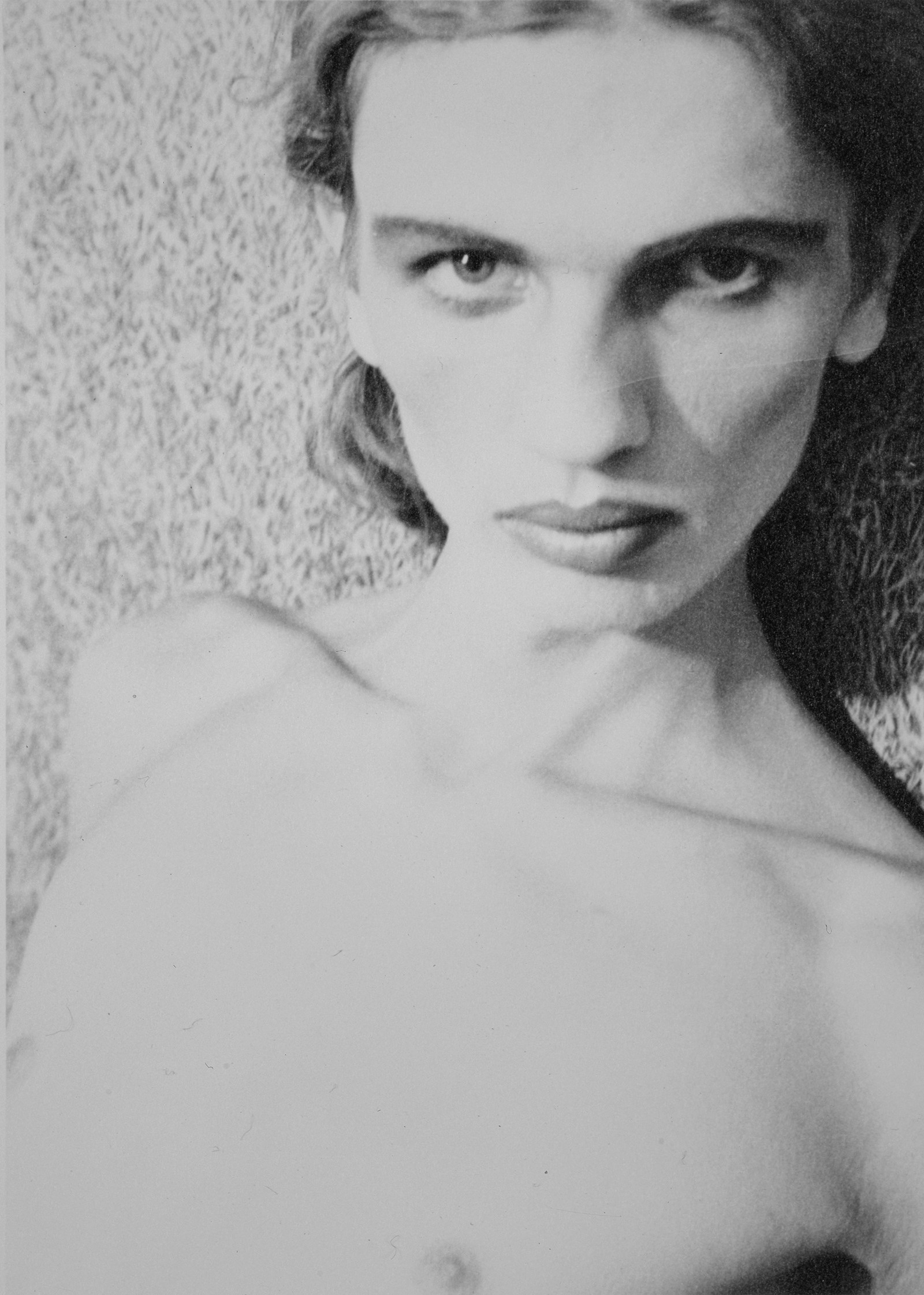

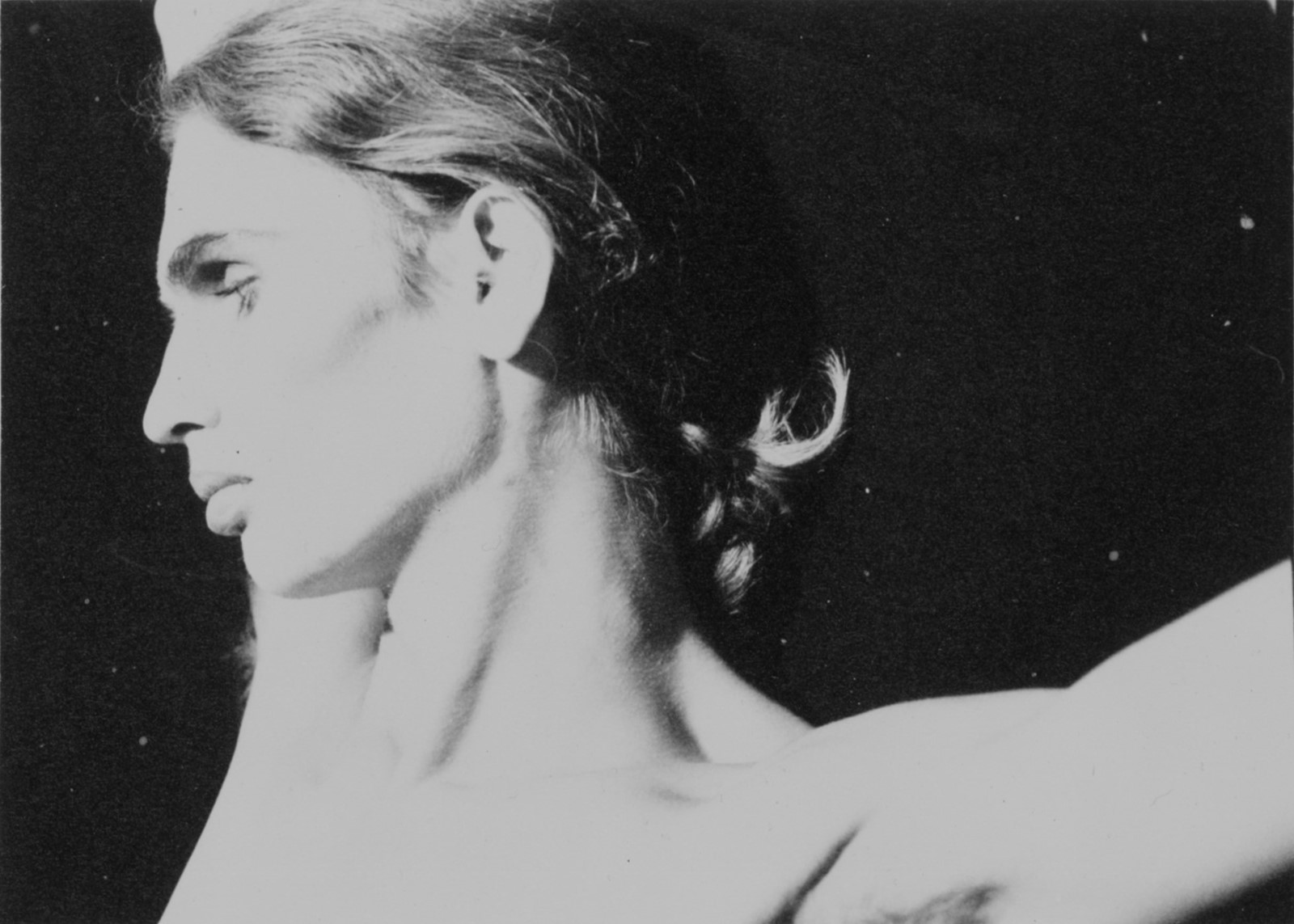

One such body of work is Carlo Joh – a series of portraits of the eponymous subject taken over the course of a number of months in 1973. “There was a big exhibition in Lucerne, and the curator told me ‘you should make some work this exhibition’. So I did – I met this boy, Carlo Joh, and he visited a number of times.” Each time he did, the photographer tells me, he was a little thinner – nonetheless, he photographed him each time. He died soon afterwards, Pfeiffer discovered. “He was 18,” he says, sadly. It’s a memory which demonstrates all too clearly Pfeiffer’s founding belief – that beauty is innately ephemeral. “I have to be quick,” he says. “Maybe it lasts one season, two seasons. But then they have to leave, or there’s drugs…” Nonetheless, Pfeiffer’s determination to find optimism in his imagery remains resolute. “I wanted to show the positive part. That is why I am out of the street life, it was not my scene. Mine was positivity, colour, sensuality. And humour, in a way, too.”

“If you want something that desperately, you have to wait. You have to have a longevity; if you don’t have this you disappear” – Walter Pfeiffer

In fact, Pfeiffer’s photographic career almost didn’t get off the ground at all. “I was from the country, and I wanted to go to art school so I went to Zurich with my father to do the exam but they didn’t take me.” Unsure of what to do next, a family friend mentioned to his mother that the city’s department biggest store was looking for a window dresser. “Unfortunately the store is gone now, but it was called Aepa, and they had everything you could need in life,” he tells me. “It was three stories high, with so many sales girls, all in yellow uniforms.” He spent four years there learning about the power of composition to entice a potential customer, before reapplying to art school. This time, he was successful.

It was the 1960s, and with a syllabus comprising Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol, and a new understanding of the nuance of social relationships, Pfeiffer set about creating his own community of outsiders. When he left, however, it was to create drawings, not photographs. “I never had a camera, but then I bought a little white Polaroid for 40 francs. If I had a still life to draw, I made a photo and drew from that.” While he drew, his group of close friends would sit on his bed, watching and chatting. “Then one day I was drawing and they said, ‘oh let’s do a picture!’ And so it started…”

That was some 50 years ago, and in the years that have elapsed since Pfeiffer has amassed an extraordinary body of work. Yet, he insists, he is still an amateur. Did he never want fame for his photography, I ask? “Yes, desperately!” he admits. “But if you want something that desperately, you have to wait. You have to have a longevity; if you don’t have this you disappear. And so you come and you go, you come and you go.” Therein lies his magic; while the audiences have come and gone, Pfeiffer has remained, steadfast.

Another Kind of Life: Photography on the Margins runs from February 28 until May 27 2018, at the Barbican Art Gallery, London.