From his initial art school rejection to his Modernist childhood home, we speak to the iconic artist as his new exhibition opens in Los Angeles

“I’ve had a couple of openings now where many, many people wore stripes for me,” says the Los Angeles-based artist Peter Shire. Today his long-sleeved striped shirt, which Shire’s studio manager calls his “uniform”, is red and has been teamed with a bright yellow undershirt and a lime green puffer jacket. “I’m being very cognisant and careful about the grouping and the colours,” he explains. “Like with this one, I distinctly wore a yellow shirt underneath because you’ve got to have a little yellow if you’ve got a bit of red, and if you have a bit of red you have to have a bit of blue or – in this case – green. I feel that many things that I do are testing the colour combinations I want to paint the pieces.”

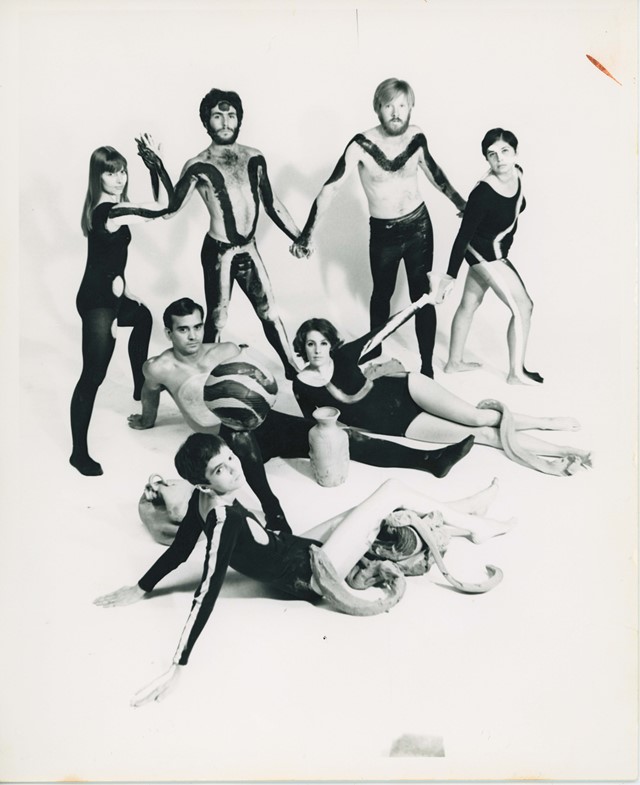

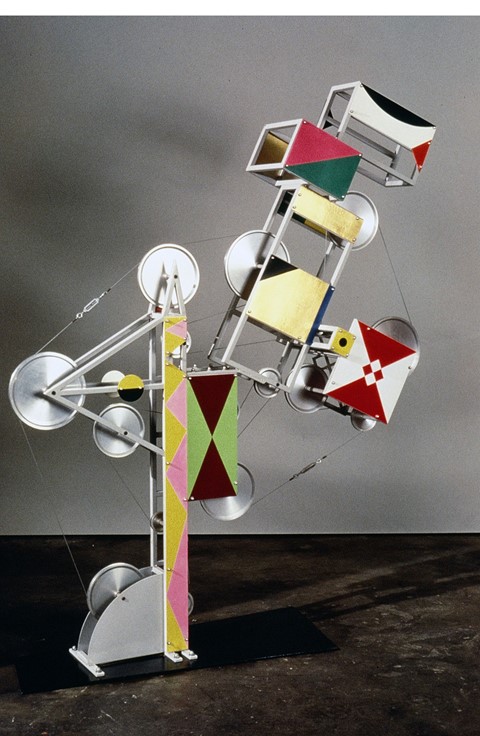

It should come as little surprise that a founding member of The Memphis Group, an Italian collective famed for their bold and colourful approach to product design, is a jaunty dresser. Since the 1970s, Shire has delighted in pushing the boundaries of good taste in everything that he turns his hand to, whether it’s pottery, furniture design or public sculpture – creating an instantly recognisable visual language that prioritises humour, whimsy and sensuality above all else.

On the occasion of the exhibition Peter Shire: Drawings, Impossible Teapots, Furniture & Sculpture at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Shire talks to AnOther about kitsch, Modernist architecture and formative memories.

On his early brush with failure...

“I got rejected [from art school]. They told me my drawing wasn’t strong enough, and I got to take a qualifying class and was just drawing to develop a portfolio. It was very operative for me because it was really important to have that anxiety... of having to really go for it and create discipline. For a lot of the kids that went into the school it was sort of a giggle. It wasn’t do or die. They’d go and smoke weed on the roof and wander off into their bedrooms to get bohemian [laughs]. They didn’t have that structure and a lot of them flubbed out.”

On kitsch...

“‘Kitsch’ is a terrific word. Ask anyone what it is and they will tell you something different or say, ‘Well I don’t know how to define it but I know what it is’. We like the dictionary, because the dictionary is semantics and semantics are what form our common philosophy. I searched and searched through various definitions that were equally divergent and the one that came out as the most definitive in my mind is: ‘Kitsch is the substitution of real values for spurious values’. The example would be the substitution of real flowers for plastic flowers.”

On finding inspiration in unexpected places...

“My dad was a carpenter. We made things as children, not only things that I had dreamt up, but we did furniture for people’s houses. [Our] little yard became a cabinet shop and it had a pile of wood in it. This wood pile was probably about four feet deep and when work needed to be done the saw got dragged out and the woodpile got fished through and taken apart to find what you needed. Probably one of the big influences on both my brother and myself is how this woodpile got reconstituted once you were done with it. Because it was a jigsaw puzzle of all these completely unrelated size: it was all wood, and it was square, but it wasn’t all 2x4. I attribute that as one of the biggest influences on us. It comes into fitting these pieces together that I make and stacking a kiln.”

On the folly of Modernist architecture...

“We lived in a Modernist house and the thing about Modernism is that it doesn’t allow for anything else: there’s no place for family photos, there’s no place for knick-knacks that people give you that are totally disgusting but you love the people so much you keep them, there’s no place for all the kind of junk that one picks up along the way; and there is definitely no place for making furniture, making art and doing stuff that isn’t controlled.

“One of the great stories [about Modernist architecture] is coming out of the parking structure and going ‘God, why do I have to walk all the way to the end of the drive? I could just go through these bushes and I would be right there.’ Then you look and there is a pathway beaten through those bushes, and do you know what they call that in architecture? Desire lines.”

Peter Shire: Drawings, Impossible Teapots, Furniture & Sculpture runs at Kayne Griffin Corcoran, Los Angeles, until May 12, 2018.