A pioneer of a new movement in photography, Vivian Cherry’s compelling images capture the restless streets of mid-century New York

In the 1940s, as the Second World War raged through Europe, a bustling New York found itself the cultural capital of the world. This was the decade that birthed the Beat Generation and Abstract Expressionism, and championed a radical realism in photography. “The older photographers working at this time wanted to make pictures that looked like paintings but reality was coming up, and that was really great,” explains photographer Vivian Cherry, who came of age in this exciting period and whose work is the focus of a new exhibition at the Daniel Cooney Gallery in her native New York.

Before she found photography, Cherry, who was born and raised in Manhattan, had been making her living as a dancer, both in nightclubs and on Broadway. But a knee injury brought about a forced hiatus in her chosen career, and found the young Jewish performer seeking out another form of income. “I was walking by a printers called Underwood and Underwood and I saw a sign saying, ‘Darkroom Help Wanted! – No Experience Necessary!’” she recalls. “I remember it was the ‘no experience’ bit that caught my attention – I didn’t know what the job would entail. At that time they were short on people to print photographs because so many men had been drafted, so I applied and got the job.” She soon honed her skills as a printer, all the while growing increasingly curious about image-making itself.

“Eventually I got myself a 35mm camera and just started walking the streets taking pictures,” the photographer, now 97, explains. Cherry’s knee healed and she returned to Broadway, dancing in a production of Showboat, but photography had become her burning passion. “Dancing is wonderful,” she says, “but you don’t get much of reality.” Looking to further her photographic skills, Cherry began seeking out photo exhibitions and permanent displays to study the work of other image-makers she admired: “Helen Levitt, Dorothea Lange, Paul Strand and Fons Iannelli were my favourites.” In 1947, she joined the Photo League, a collective of professional and amateur photographers, founded by Sid Grossman and Sol Libsohn during the Great Depression, and dedicated to addressing societal issues through photography.

This documentary approach was right up Cherry’s street; she soon turned her lens to subjects such as Navajo and Pueblo Indian healthcare and a West Virginia doctor devoted to the treatment of miners, selling her essays to a number of prominent publications. She continued to snap figures who caught her interest in and around New York, from those frequenting the Third Avenue EL to the families gathered on the stoops of Spanish Harlem. The resulting images are brilliantly candid – a young man in a bowler hat, glancing skywards, seemingly unaware of the camera pointing in his direction; a woman in a headscarf, lost in thought as she gazes from a train window. “It’s funny because now everybody has a camera, but back then the people I photographed didn’t pay much attention to me,” Cherry muses on the unselfconsciousness of her protagonists. “And if somebody didn’t want their photograph taken, I didn’t take it... except that I did too,” she chuckles conspiratorially. “Because if I saw something interesting, I’d put my camera to my eye straight away and shoot, and if someone started yelling at me, I’d turn around and say, ‘I didn’t do it!’ and then I’d walk away very fast!”

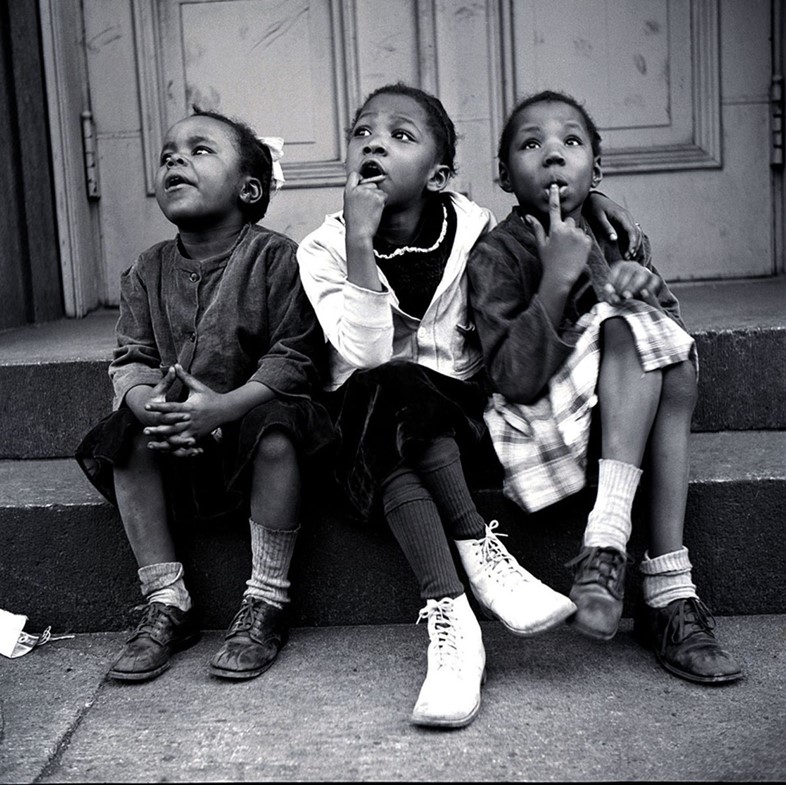

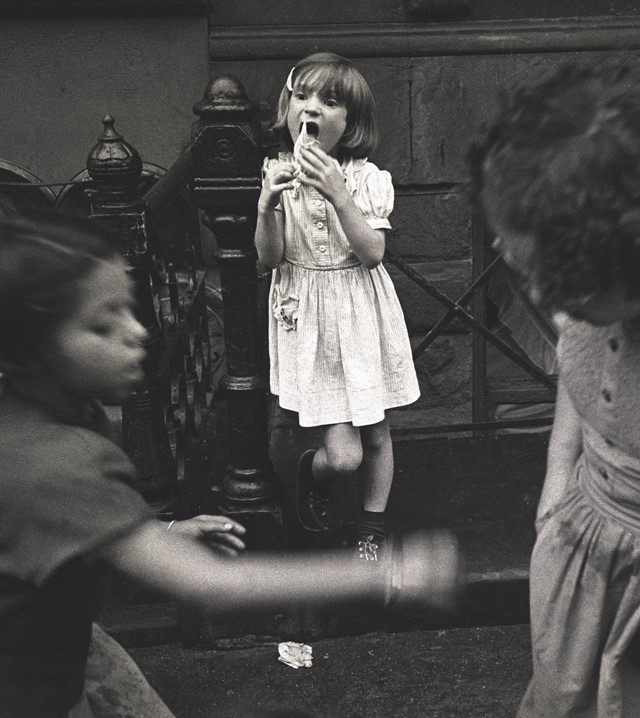

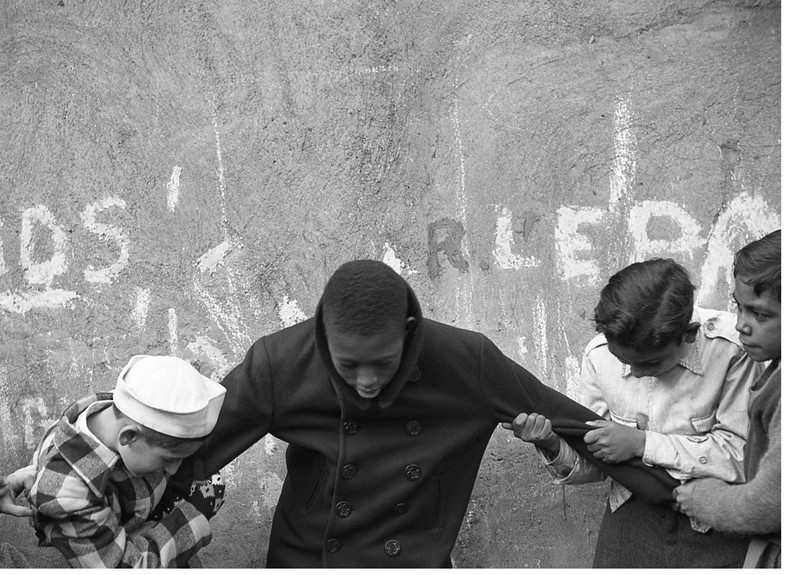

It is this aptitude for spotting an interesting photo opportunity and snapping it in a split second, with expert ease, that so sets Cherry’s work apart. Indeed, many of her most stirring photographs centre on children, the most restless of all human subjects, playing in the street. “It was easier to take pictures of children then than it is now because they’d always be running around in the open spaces in the city, playing cops and robbers and shooting each other with their fingers,” she says. In one particularly jarring series, a group of kids of various ethnicities engage in a game of lynching, taking it in turns to play the victim of the atrocity. “I was horrified, so I watched it and I photographed it,” Cherry remembers. “They’d have heard about it on the radio or from their parents – that was the period of lynching, that violence was their reality.” Such poignant social and political undertones are another trait of Cherry’s work, rendering her images vital historical documents of New York City life as well as moving studies in humanity.

Cherry continued to photograph her beloved New York over the decades, documenting the ever-changing landscape of the city and its vibrant cross-section of inhabitants. Her work has been widely recognised and today forms part of the permanent collections at MoMA, the Smithsonian, the National Portrait Gallery and many other such institutes. She has produced four photobooks to date, and in 2000 had a solo retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum. This latest exhibition centres on her earliest series, in 40s and 50s New York, and presents the perfect opportunity to observe what photo curator Julia Van Haaften aptly describes as her “directness, modesty and... open heart [and her ability to capture] distinctive details while indelibly reflecting and illuminating the big picture issues of our modern times in politics, art, racial equality, women’s autonomy, and personal integrity.” Cherry was one of the original street photographers, and although she’s no longer able to capture pictures (having carried on shooting until well into her 90s), she still views the world with an indelible photographic sensitivity. “When I walk the streets now, I’m pushed on them,” the remarkably witty and articulate nonagenarian says as our phone call draws to a close, “but I still look at life as I would through my camera.”

Vivian Cherry: Helluva Town is at Daniel Cooney Gallery New York until June 23, 2018.