When Greece pulled out of the 1948 Venice Biennale, Peggy Guggenheim seized her chance to show in its place; now, 70 years on, her palazzo pays tribute to her powerful impact

“The 1948 Biennale was like opening a bottle of champagne,” according to Peggy Guggenheim’s assistant Vittorio Carrain. “It was the explosion of modern art after the Nazis had tried to kill it.” If the Biennale itself was the champagne, Guggenheim’s artworks were the bubbles that made it fizz.

When the Venice Biennale resumed after WW2, Greece, ravaged by its civil war, was unable to contribute. Transforming the loss into an opportunity, director Rodolfo Pallucchini invited Guggenheim to display her private collection in the Greek Pavilion. Little did he know how crucial it would be to that year’s display. Although larger pavilions showed retrospectives of Picasso, Impressionists, and the “degenerate” art the Nazis had tried to ban, it was the Guggenheim pavilion that caused the most commotion.

Cubism, Futurism, Abstraction and Surrealism all found a home: there was room for all. It was an inclusion that anticipated “what would become the role of the postwar Biennales,” according to Grazina Subelyte, the curator of a new homage exhibition to this “milestone event” at the Guggenheim museum in Venice. For Subelyte, the chance to revisit the original show “reveals just how progressive and forward-thinking Guggenheim was as a patron and collector”.

The Show

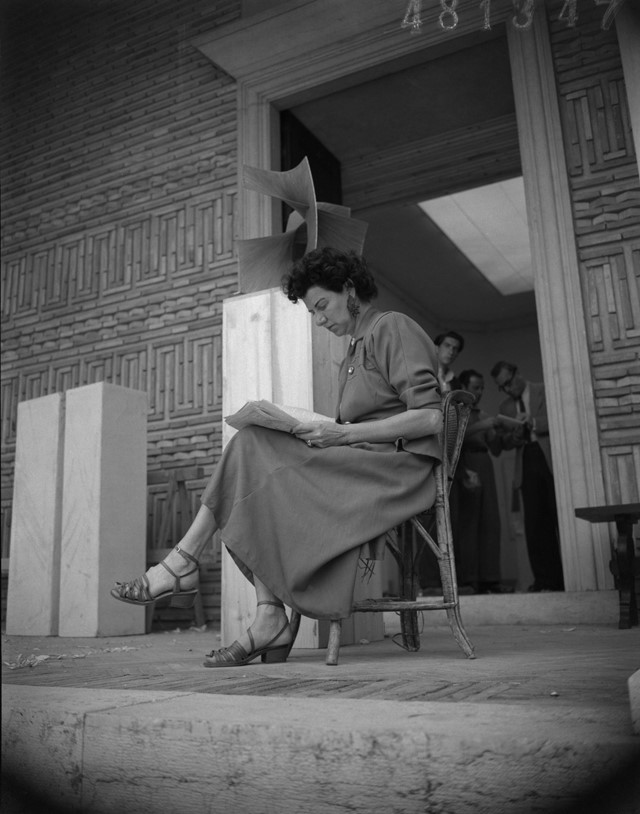

The Greek Pavilion sits at the back of the Biennale Gardens, across a small bridge flanked by an olive grove with a triple-arched entrance. Its high, windowless walls provided the perfect canvas for Guggenheim, who crowded them with 136 works from 73 artists. The result was a vibrant chamber of colour. There, Kandinsky rubbed shoulders with Klee, Pollock and Motherwell; Rothko and Man Ray glowered down from white-washed walls; Calder mobiles gently twirled in the breeze. It was a scene that captivated and confused its audience in equal measure. “The pavilion was one of the most popular of the Biennale,” Guggenheim proudly noted in her memoirs. “What I enjoyed most was seeing the name of Guggenheim appearing on the maps in the public gardens next to the names of Great Britain, France, Holland… I felt as though I were a new European country.” “She was truly ahead of her time,” Curator Grazina Subelyte agrees. “Her pavilion received much attention and praise, although not everyone understood it.” This critical confusion can be seen in some press headlines. “The Exhibition of Wonders or Guggenheim’s Noah’s ark?” one reads. Another, cruelly succinct: “Apologies, We Laughed.”

The People

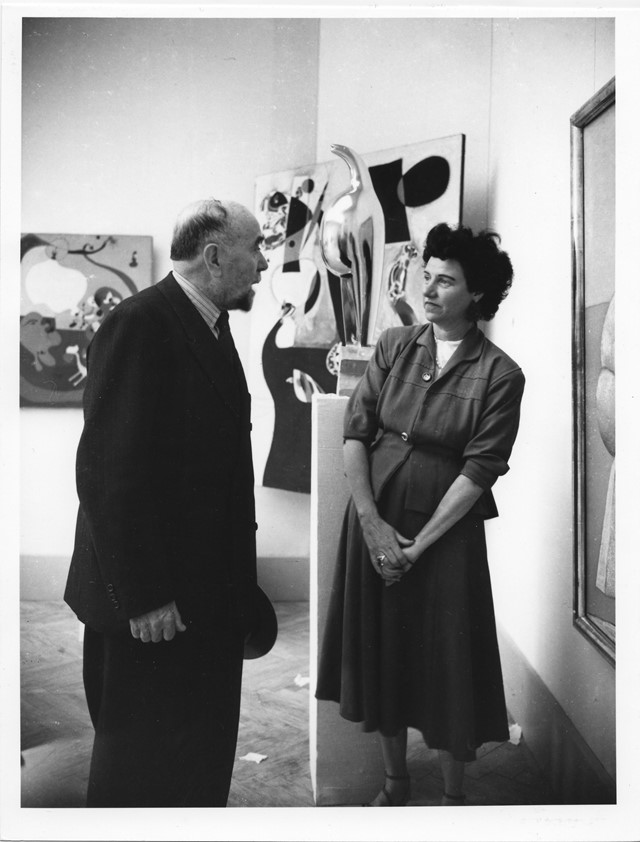

Guggenheim’s pavilion became a thriving centre for artists as well as art. Flanked by her Lhasa Apsos (the only dogs allowed in the Biennale, who – according to Peggy – could always be found near the Picassos, or in the restaurant Paradiso being fed fresh gelato), Peggy received guests from all over the world. A photograph of art historians Alfred and Margaret Barr features in the exhibition, as does one by Lee Miller, who caught a joyful Guggenheim next to critic Lionello Venturi. Another critic, Bruno Alfieri, remains one of the unsung heroes of Guggenheim’s show; as she recalls, he “saved a dismantled Calder mobile from being thrown away by the workmen, who thought that it was bits of iron bands which had come off the packing cases.”

Friend and admirer Henry Moore frequently popped over from the British Pavilion (he won the Grand Prix for Sculpture) for good conversation and company. Other visitors included the Italian President Luigi Einaudi and Bernard Berenson, whose writings on Renaissance art had been Guggenheim’s first guide to Europe. Guggenheim recalls his visit vividly: “I greeted him as he came up my steps and told him how much I had studied his books and how much they had meant to me. His reply was, “Then why do you go in for this?”” Her reply? “I consider it one’s duty to protect the art of one’s time.” It’s no wonder that Miller went on to describe Guggenheim’s pavilion as “the most sensational,” in British Vogue.

The Impact

70 years later, the legacy of Guggenheim’s show remains stronger than ever, and not only because it was the first time artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still were shown outside the United States. For Guggenheim it was a moment of personal significance too, as shortly afterwards she settled in Venice for good. She bought the unfinished Palazzo Venier dei Lioni, a bungalow on the tip of the Grand Canal, and set about painting her bedroom turquoise and hanging her intricate silver bed-head from Calder. Guggenheim’s bravery, both in relocating to a new country and in having the courage to stand by the art she loved, invoked a new spirit in the Biennale to challenge and not merely comfort its audiences. It is a disposition that continues to this day.

In Subelyte’s exhibition the attention to detail is impressive, bringing together original works, letters, photographs and a copy of the original pavilion installation, designed by Carlo Scarpa. “I thought it was of utmost importance to reconstruct the original” Subelyte confesses, explaining how she and Ivan Simonato used the ten black and white images from the Biennale archive to create the “intricate model”. Even the sign drawn by Scarpa that hung at the entrance of the pavilion – “Collezione Peggy Guggenheim” – sits above a doorway replicated perfectly. It is exhibitions such as this which – in Subelyte’s words – “help us to recollect and shed light on what should not be forgotten through the passage of time”. The genius of artists such as Calder, Pollock, Rothko and Ernst remains unquestioned in the artistic canon today, yet the value of the woman holding their work aloft for the world to see, positioning canvases and hanging mobiles in an exhibition that came about by chance, has yet to be fully realised.

1948: The Biennale of Peggy Guggenheim, runs from May 25 until November 25, 2018 at the Peggy Guggenheim Museum in Venice.