It’s hard not to fall in love with the timeless elegance of Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s sublime pictures of the Belle Époque – the 1920s flappers, the car parades, the parties in full swing, the Parisian boulevards or the scorching Côte d’Azur sun were all exquisitely captured in the image-maker’s iconic black-and-white frames. Tinged with Proustian nostalgia and an aura of innocent decadence, the era’s scenery famously provided the backdrop for the legendary photographer’s early life, and some of his most memorable works. Surprisingly, however, it wasn’t until 1963, when John Szarkowski – the New York MoMa’s greatly influential director of photography – decided to exhibit a selection of his images, that a 69-year-old Lartigue first embarked on a path to recognition outside his native France.

Over three decades after his death, London’s Michael Hoppen Gallery is dedicating an extensive retrospective to some lesser known fragments of the modern photography pioneer’s vastly prolific career. Curated by designer Paul Smith in collaboration with Michael Hoppen, the exhibition focuses on Lartigue’s later works, specifically spotlighting the 1960s and 70s, the artist’s affinity with the world of fashion, and his personal archives, which have been painstakingly preserved by the French government.

“Lartigue kept a diary for every day of his life from the age of eight,” Michael Hoppen tells AnOther. “There are about 75 of these diaries, and they’re all preserved by the Ministry of Culture in Paris. Thankfully, Paul and I managed to gain access to them, and we discovered all these hidden treasures – the diaries were illustrated with hundreds of drawings and photographs from the post-war era, which most people are unfamiliar with.”

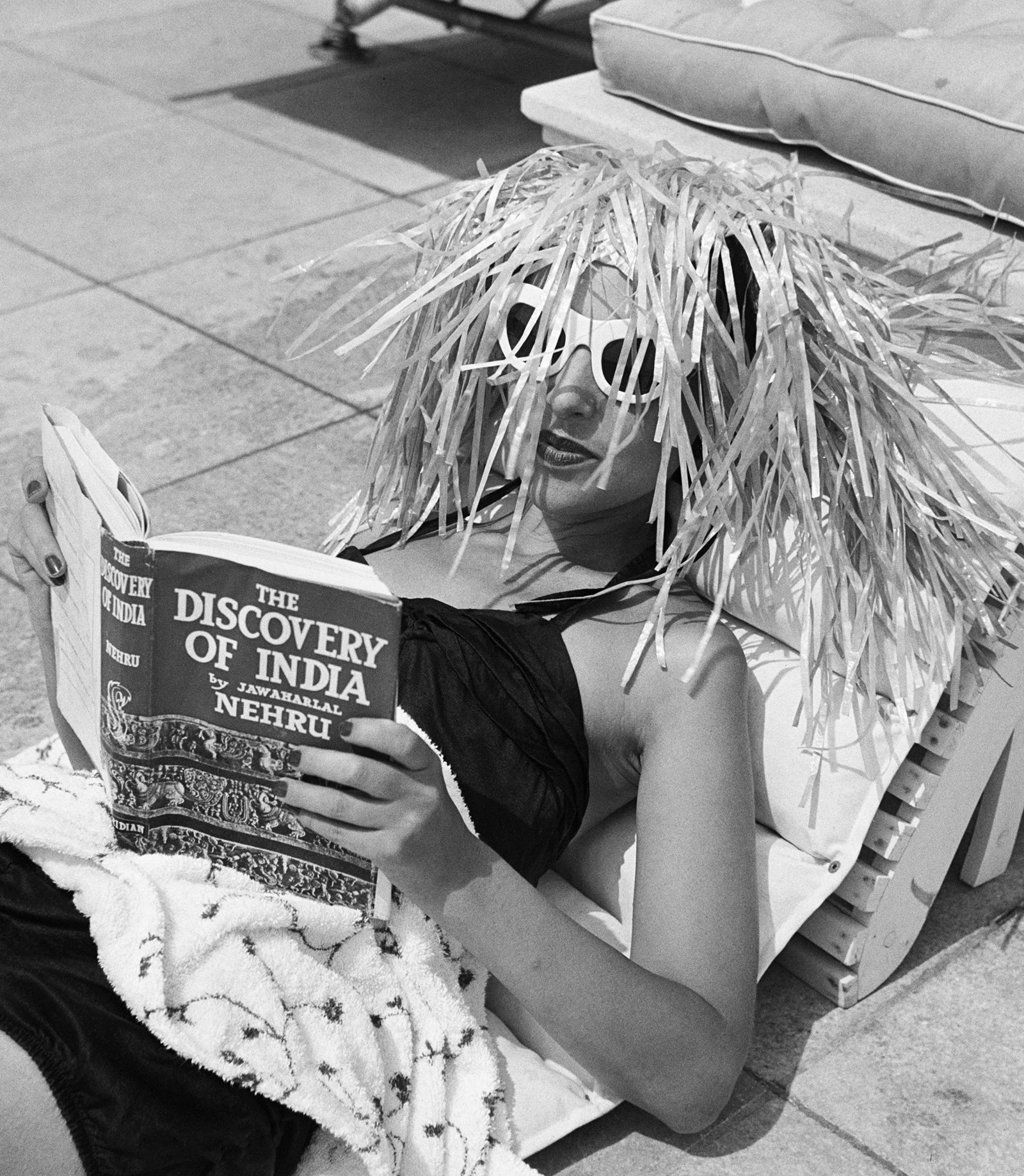

Following his arrival to the United States in the early 60s, Courbevoie-born Lartigue swiftly espoused the change in his surroundings without failing to stay true to the spirit of magic, playfulness, and spontaneity that inherently defined his photographic eye. “I’ve always been attracted to the simplicity of his imagery,” explains Paul Smith. “There’s no elaborate setup, no complicated lighting, it’s all very much about the ‘caught moment’ – and even when working with fashion specifically he never needed to overdo things.”

“I’ve always been attracted to the simplicity of his imagery. There’s no elaborate setup, no complicated lighting, it’s all very much about the ‘caught moment’” – Paul Smith

Lartigue’s transition into the world of fashion photography was a late yet organic one. Initially commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar, where he worked closely with then-art director Ruth Ansel, the photographer quickly made a name for himself as the visual artisan of a candid, glamorous yet unpretentious spirit of insouciance. “There is so much that I found out about Lartigue whilst curating this exhibition, and I think that his fashion work is often quite under-explored,” argues Smith. “For instance, I never knew about his relationship with Richard Avedon, and the fact that his first published book was actually a collaboration with Avedon. He was also friends with Cocteau, Picasso and so many other chic people that fashion naturally played a role in his photographs – yet despite the undeniable glamour, what he loved the most was to capture the spontaneous, the ordinary.”

Indeed, the photographer’s artistic philosophy and love of simplicity largely influenced Smith’s own approach to style and creativity. “People often ask me where I find inspiration,” he says. “I just answer by saying ‘it’s all around you, you just have to look and see!’ The same thing was true of Lartigue. He found inspiration in the most familiar and everyday places.” Much of the honesty and fun emanating from the artist’s work is due to an irresistible, uncanny ability to capture people revealing themselves – a complete lack of artifice which never fails to seduce. “If someone points a camera at me, or if I point a camera at you, you’ll instantly prepare yourself for the picture, you’ll start posing, thinking about the outcome,” asserts Hoppen. “In those days, people weren’t afraid of the camera, and there was always a bit of magic that came out of this carefree attitude.”

“In those days, people weren’t afraid of the camera, and there was always a bit of magic that came out of this carefree attitude” – Michael Hoppen

A collaborative project between two different perspectives bound by a shared admiration for Lartigue’s vision, the exhibition brought together Hoppen and Smith in a truly seamless manner. “Paul has an incredibly acute eye for style and nuance,” explains Hoppen. “He has this great ability to empathise with the modern world, while at the same time finding value in tradition, which is very much what Lartigue was about.”

Ultimately, Lartigue’s photographs ought to be taken as a reminder of the importance of lightness and humour. “This isn’t Miró or Picasso, it’s Lartigue – and Lartigue was about making people smile,” concludes Smith. “You know how people ask you what you’d take with you on a desert island? I’d probably take some of Jacques’ pictures, because they make me smile, and I would miss the humanity of watching people interact in such a positive way.”

Jacques Henri Lartigue... C’est Chic runs until July 28, 2018, at Michael Hoppen Gallery, London.