For her formative 1985 work The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, Nan Goldin eschewed the traditions of exhibiting photography by compiling her images – the number of which ran close to 700 – into a slideshow, and screening it alongside a soundtrack featuring, among others, Yoko Ono, Maria Callas and Dionne Warwick. The 45-minute long show has since been screened in galleries and museums all over the world, and is lauded for its searing candour and highly personal subject matter – the series comprises photographs taken by Goldin of her friends, family and burgeoning subcultures in cities like Boston, New York and Berlin. The photographer has repeatedly referred to The Ballad of Sexual Dependency as something of a diary: her personal experiences – and indeed those of her subjects – play out before the viewer, revealing an unprecedented intimacy between Goldin and the people she captures, and by extension between the photographs and the audience.

In 1986, following its first showing at the Whitney Biennial in New York, Goldin spoke to Aperture’s Mark Holborn. This revelatory interview is reproduced in Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present, a new book from the New York foundation that compiles extraordinary interviews with photographers and artists from the magazine’s publishing history. To say that the roster of names featured in the fascinating tome is impressive would be belying its brilliance; Henri Cartier-Bresson, Bruce Davidson, Tacita Dean, David Hockney, Nick Knight, Barbara Kruger, Carrie Mae Weems and Thomas Ruff all feature – though that small sampling barely scratches the surface of the included names. Here, revisit Goldin’s candid discussion with Holborn, detailing how she chose the soundtrack, the process of photographing her life and peers, and how she sees the future of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

Mark Holborn: You presented The Ballad of Sexual Dependency as a large slide show with a sound track at the 1985 Whitney Biennial. What is The Ballad of Sexual Dependency? Is it a slide show, an installation, a story, a document, or a diary?

Nan Goldin: It’s the diary I let people read. I keep a written diary, but I never allow people to read it. This is my public diary. My written diary is a document of a closed world. My visual diary expands with the input of other people from its subjective, self-referential roots. A large part of my work is about the quality of the relationship between me and the person that I am photographing. It is almost a collaboration. It takes on its own life. At one point there was a series of single images; then there were slide shows for friends. Now the slide show has a title and a life of its own. The primary life of The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is as a slide show.

MH: To what extent does this diary address other people?

NG: There is a terrific universal aspect about the slide show, and I hope it transcends the specific world in which it was made and applies to the whole nature of the relationships between women and men. It addresses people who are involved in pursuing close relationships.

MH: How did it begin?

NG: I have been taking pictures of my life since I was sixteen. I was the school photographer at a Summerhill-type school. I was obsessed with recording my life. The major motivation for my work is an obsession with memory. I became a serious photographer when I started drinking because (the morning after) I wanted to remember all the details of my experiences. I would go to the bars and shoot and have a record of my life. I lived with some drag queens so I photographed drag queens. I never decided that drag queens formed a subject that I had to photograph. The work was always a direct offshoot of my life. I have a need to remember everything. The photography comes from that need. Photography provides the material for this diary.

I was nineteen when I had my first exhibition of prints. The slide shows started when I was at art school. I was bored and I would go in independent study. My work became repetitive at school. I was expected to replicate my work with the drag queens, but with more technical proficiency. My work lost its immediacy. I went back to try and photograph something I had already lived through, and it felt exploitative both to the subjects and to me. I used a wide-angle lens and a strobe, which gave the pictures a hard edge the queens didn’t like.

“I was obsessed with recording my life. The major motivation for my work is an obsession with memory” – Nan Goldin

I then went up to Provincetown and lived with the lesbian community there and photographed them. That was my life during my absence from art school. When I came back to get credits from the school, I had no darkroom so I showed slides. I started to do the slide shows in bars in Provincetown where I worked. When I moved to New York, I still had no darkroom so I continued with the slides. My first slide show in New York was at Frank Zappa’s birthday party at the Mudd Club. Then I presented shows at other clubs with music. I had a boyfriend who knew a lot about English music from the 60s, and he acted as my deejay. Then I did the show with a great band called the Del-Byzanteens that includes Jim Jarmusch, James Nares, and other Lower East Side luminaries. Their song ‘My World Is Empty’ [1981] is still in the slide show. I decided I had to make a sound track for the show.

MH: What is the difference between the slide show and an exhibition of your prints?

NG: The slide show allows me the opportunity to show seven or eight hundred images in forty-five minutes. I like the prints but I don’t worship photographs as objects. I am interested in content. The slide show enables me to make political points more clearly. It helps me to reveal my ideology. I can clarify my intentions through the juxtaposition of the lyric of the sound track and the image. The sheer accumulation of imagery as well as the editing assist the clarity. Also through the editing I can create a clearer narrative than is possible with the single images and one that has an intense emotional effect. People cry during the show; it can also be very funny. My goal is to provoke the same emotions in my audience as are described in the show.

Some of the single images are very strong on their own; others are just included to provide narrative threads. I’d like to find a way to show the prints that would have the same impact as the slide show.

MH: Why do you use Callas on the sound track?

NG: I love her voice. It has the raw quality that is despised by certain purists. I love it because it’s so passionate. To me her voice is perfect. I have dozens of sound tracks and have tried many different songs. I never show the slides in the same order, and I often change the sound track. I’ve remixed it, but now certain songs fit exactly and have been carried down for the last five years like the opening song “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” which is a Brecht/Weill piece from The Threepenny Opera [1928]. There is also “Memories Are Made of This” by Dean Martin [1955] at the end, and “She Hits Back” by Yoko Ono [1973]. There is also that song “Fais-moi mal Johnny” by Boris Vian [1955] about a woman who is asking a man to make violent love to her, who is saying “Hurt me, Johnny” while the man says he couldn’t hurt a fly. Then she says, “I’m not a fly. I like love that goes boom.” I have also used “Don’t Make Me Over” by Dionne Warwick [1963] for a long time and “Downtown” by Petula Clark [1965].

MH: How is the show structured?

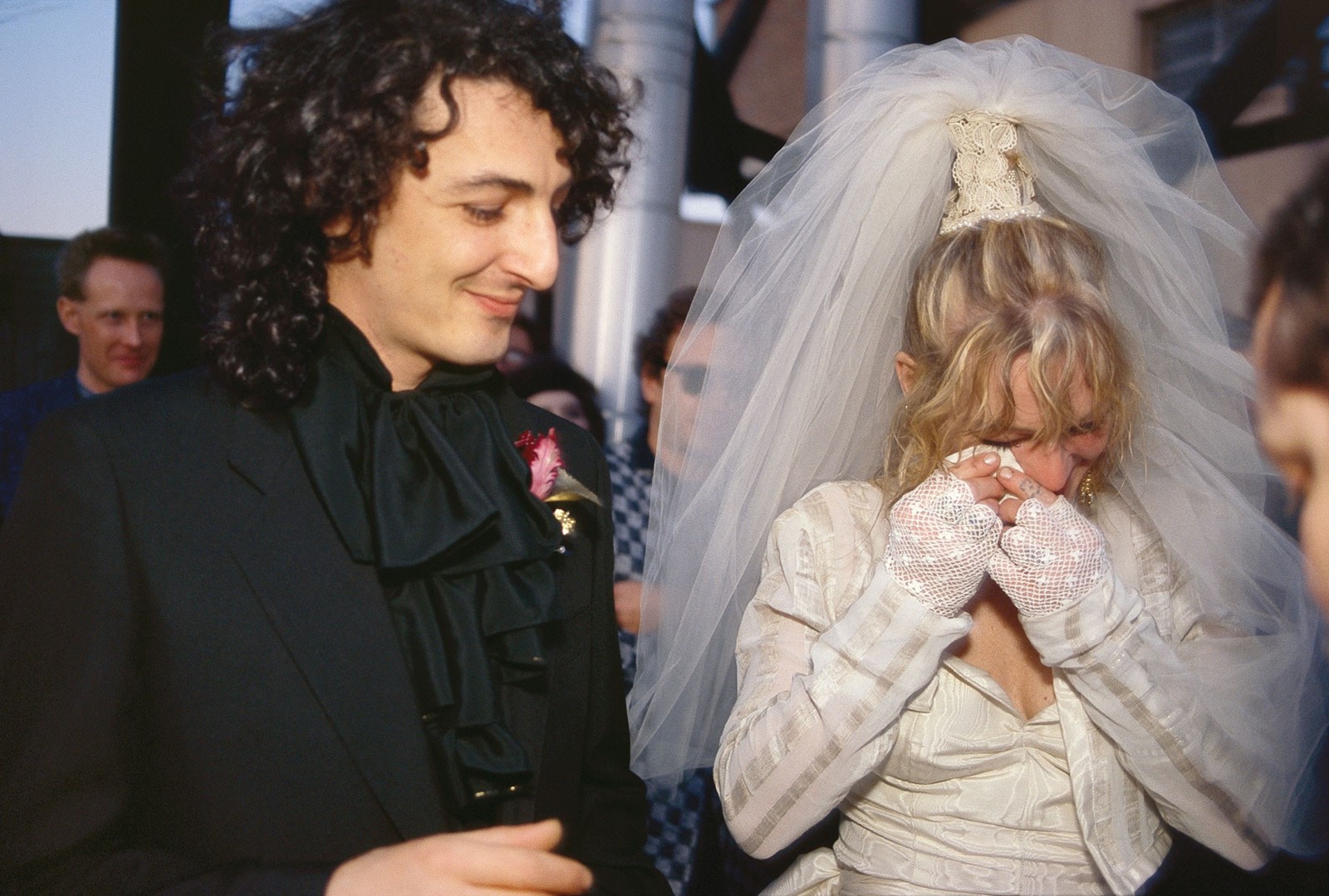

NG: It starts with portraits of men and women. One of the first portraits is of my parents when they were young. It then breaks down into genders, first women and then men. The photographs show people in terms of their images of themselves, their conditioning, their gender identification, and their relationships to each other. The women, then the men, are shown first outside in the world, then alone in their rooms; then women are shown together and men are shown together. Battered women are shown, and women who have been abused, who have been subjected to violence. Some men are shown as violent, and the conditioning of violence is explored through things such as guns and dogs. The images of women are followed by images of prostitution, brides, and mothers, so there is a sequence of the mother, the whore, the bride, the sexual woman, and introspective woman. The children are shown with their parents, by themselves, and the boys are shown fighting. The drag queens are shown as the third sex, not as men dressed as women. They are shown in a world of their own, in their clubs, in their jobs, on the street, in their home lives, and their relationship with lovers. There is a long section of men alone in their rooms masturbating with that version of “My World Is Empty.” There are pictures of a group of skinheads in London. The show enters the downtown world with the song “Downtown,” and it includes parties and fashion, the clubs and the bars. It continues with couples. There are couples together and couples in bed having sex, followed by images of empty rooms, empty beds, and graves. At the end there is a Mexican couple in their seventies who got divorced a week after the picture was taken. The final image is of skeletons coupling after they have been vaporized. In spite of it all, people have a need to couple. Even when they’re being destroyed, they’re still coupling. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency starts and ends with this premise, but in between there is the question of as to why there is this need to couple and why it is so difficult.

MH: How much is the dependency you describe something that you see in others, or how much is it in yourself?

NG: It comes from myself and I see it in the people around me. I think that men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other, irrevocably unsuited. It is almost as if men and women are from different planets, they have such difficulty understanding each other. I find men, or the male emotional system, very difficult to understand. Men seem to be afraid of women. Emotionally I am much more suited to be with a woman, but then there is this sexual desire for men. I realize my emotional and sexual need for the opposite sex. The slide show touches my gay relationships too; I am dealing with the difficulty of coupling, and part of that is the difficulty of maintaining intimacy. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is an exploration of my own desires and problems.

MH: You never feel like a voyeur?

NG: The premise that a photographer is a voyeur by the nature of photography is just not true. The people who have been photographed extensively by me feel that my camera is as much a part of their life as any other aspect of their life with me. It then becomes perfectly natural to be photographed. It ceases to be an external experience and becomes a part of the relationship, which is heightened by the camera, not distanced. The camera connects me to the experience and clarifies what is going on between me and the subject. Some people believe that the photographer is always the last one invited to the party, but this is my party, I threw it.

“I think that men and women are irrevocably strangers to each other, irrevocably unsuited. It is almost as if men and women are from different planets” – Nan Goldin

MH: The photographs have been shot from Mexico to Berlin, to Boston, to New York. You describe them as touching universal qualities, yet is there a particular sense of location?

NG: People in Philadelphia said it wasn’t about them. People in San Francisco said it wasn’t about them. People in the north of Sweden said it wasn’t about them. People in Berlin said it was about them. People want to believe if they don’t look like the subjects of my photographs, then it’s not about them – it is specific to the people and locales of my own life, but the concerns are concerns are universal.

MH: What unites Berlin with a certain part of New York?

NG: We identify ourselves as New Yorkers rather than Americans. The lifestyles and aesthetic of the subcultures of the two cities are similar.

MH: You once casually said that the slide show was the flip side of Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise [1984]. The phenomenal response to that film involved the audience’s identification with specific characters, attitudes, and location. It may have had something to do with sunglasses.

NG: It has something to do with sunglasses. Stranger Than Paradise appealed to me less because of its reference to Lower East Side New York than for its description of being a stranger in America. That film is less about what the characters look like and more about being an immigrant. But both the film and my slide show are specific in that they involve people who look a certain way. Even if the slide show involves some people who keep nocturnal hours, drink heavily, or do drugs, the issues are universal.

MH: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency has a narrative structure with bridges between the sections. You are presenting a flow of images in a darkened auditorium with a sound track. The next logical stage would seem to be a film.

NG: There is a sense of time in the slide show. Characters age, couples break up, are revisited, and there is a narrative that lends itself to film. I would love to be shooting film, btu there is an advantage to the slide show because it can be constantly reedited. The editing is subjective; it’s affected by how I’m feeling about the issues it explores at the time I’m working on it. It can become brutal and violent according to how angry I feel. Other times it can be more optimistic.

MH: Do you view your recent fashion photographs shot in the Russian baths on the Lower East Side as distinct from your personal work?

NG: I see no distinction on that job. I could do exactly what I wanted. I used my people and my location. That’s why they work as photographs. One’s constantly looking for assignments that allow that freedom. Everything I shoot, even commercial jobs, can go into the show if I like it.

MH: Is the ballad finite? Does it go on growing and growing, or will it reach a definitive version?

NG: It can never be perfect. Next week I am putting it on video for the first time. It will then exist outside of my control. But this is not the final version. I will continue to reedit it. It’s my Leaves of Grass, constantly updated and revised.

Aperture Conversations: 1985 to the Present is available now.