Six of Tish Murtha’s gritty, impactful series go on show at The Photographers’ Gallery this week, shedding a new light on her powerful oeuvre

Who? In the landscape of British documentary photography of the latter decades of the 20th century, Tish Murtha’s is not a name that is often referenced. Image-makers like Martin Parr, Homer Sykes and David Meadows pioneered in those years, but Murtha also consistently created impactful photographs of Britain’s sidelined social communities. “I think what Tish captured compared to some other photographers – there was a lot of the working classes looking gritty but resolute, poor but happy – she captured a melancholy as well, and difficulties as well as enjoyment,” says Gordon MacDonald. “She caught more aspects of working class life than a photographer who’s coming in from the outside to a community possibly could.” Alongside Val Williams and Karen McQuaid, MacDonald has curated Tish Murtha: Works 1976–1991, which opens at The Photographers’ Gallery tomorrow. Bringing together six of Murtha’s series, the exhibition highlights how the photographer documented society’s substratum: regulars drinking in a Welsh pub (Newport Pub); life and traditions of the working classes in the North East of England (Elswick Kids, Juvenile Jazz Bands, Youth Unemployment and Elswick Revisited); and the sex industry in Soho (London By Night).

The third of ten children, Murtha was born in 1956 and grew up in Elswick, Newcastle, and enrolled in David Hurn’s School of Documentary Photography in Newport, Wales, aged 20, having done a photography night course in her hometown. Hurn remembers Murtha’s as the “shortest interview I had ever done”: “I asked her what she wanted to photograph and she said, ‘I want to take pictures of policemen kicking children,’ and I said, ‘You're in’... I knew exactly what she meant and I knew she was going to be a social photographer.” It was while learning under Hurn that Murtha produced Newport Pub, an accomplished and captivating study of the characters in a local establishment. “I think early on at Newport under the tutelage of David Hurn she really found her style and her way of working and developed it very quickly,” says MacDonald. “Those ways of understanding marginalised experience and understanding, first the small group of people getting drunk in this pub, in that closed environment, that small society.”

What? She continued to train her lens on the marginalised in society. Hers was an atypical angle: while a documentary photographer would normally go in as an outsider, with a stark objectivity towards their subject, Murtha’s work was defined by empathy. “There’s not the exoticisation,” MacDonald explains. “She’s not walking in there and saying ‘wow look at this, there’s kids with dirt on their face and holes in their shoes’. She was going in there understanding that that was the case, and photographing what was important about it.” Take the subjects in her series Elswick Kids and Youth Unemployment, for example: “In some of her projects, she was related to those people: they were her brother’s friends or her friends or the kids of people she’d gone to school with,” MacDonald continues. “There was a relationship there which ran much more deeply than they do normally in documentary photography projects.”

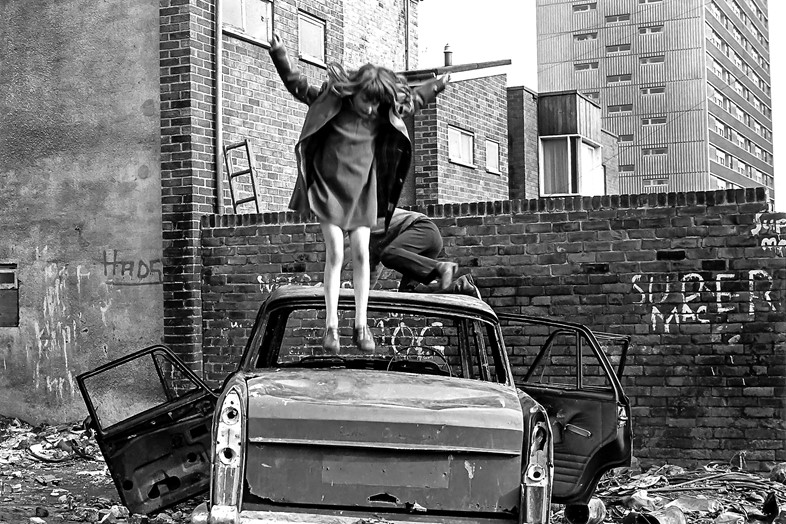

Through her work, Murtha shed light on some of the social issues affecting the North East. Youth Unemployment was just that – a gritty look at how a lack of work impacted the area. The 1980 series became a political statement, and an essay Murtha wrote on the subject was recognised by the House of Commons in a debate the following year. MacDonald remarks that “most ironically, she made the series Youth Unemployment whilst on a Youth Opportunity Programme” – a government scheme designed to get young people into work. “It was really taking that scheme’s money to get her into work, and into this position of being able to make work, and at the same time criticising the government’s record and behaviour towards the unemployed. Particularly in the North East of England, which was hit hard by Thatcherism; the boom in the South East left it a bit behind in terms of employment and certainly stole manufacturing and a lot of jobs from that area.” Murtha captures something of a desolate landscape, with children playing in abandoned cars and jumping from the window of a derelict house onto a pile of mattresses, friends watching on in enjoyment. Her later series like Elswick Revisited tackle similar issues, highlighting the effects of racism, poverty and industrialisation.

Although she championed a focus on her own locale, Murtha was able to foster an innate understanding of even the subjects she was unfamiliar with. From her early work in the Welsh pubs, to London By Night, which saw her immersed in the lives of sex workers in Soho, she – and by extension her photography – was compassionate in her approach, and never “overwhelmed by the oddness or the exotic nature of [her subjects]”. This aspect of her work singled her out from her contemporaries; MacDonald describes it as “every idea having that solid base, that ‘Tish-ness’ to it”. “From beginning to end, from subject to subject – moving from that pub, as a real kind of experiment with her early practice, through Elswick, through Youth Unemployment and out to the Soho project, London by Night, and Elswick Revisited – there’s a real coherence to her practice and a concern, a real empathy that flows through it,” he says.

Why? Murtha’s astonishing oeuvre is made up of black and white prints, organised by her daughter Ella since her death in 2013. The Photographers’ Gallery’s exhibition comprises original prints kept by Murtha – some therefore are slightly damaged, owing to how she would move her archive around – as well as letters she wrote and equipment she used; including the camera that captured the six series – an Olympus OM1 – and even a letter from Hurn guaranteeing her for its purchase.

Aside from the captivating images she created, the show highlights how she was steadfast in using photography to highlight political and social injustices. She was driven, as MacDonald explains, in drawing attention to these issues: “I’ve heard it firsthand from Ella that she was bloody-minded. Her drive was to bring this to the attention of people that otherwise normally wouldn’t see it, which is what photography’s a great vehicle for. She was passionate about the kind of social conditions that people were forced to live in, the inequalities that surrounded her.” Thanks to this new exhibition, Murtha’s idiosyncratic eye and resulting photography are afforded a newfound recognition.

Tish Murtha: Works 1976–1991 is at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, from June 15 – October 14, 2018.