The last solo exhibition Matthew Day Jackson held in London was a photographic series of anthropomorphic rock formations found across the continental United States in the course of a three month road trip in 2006.

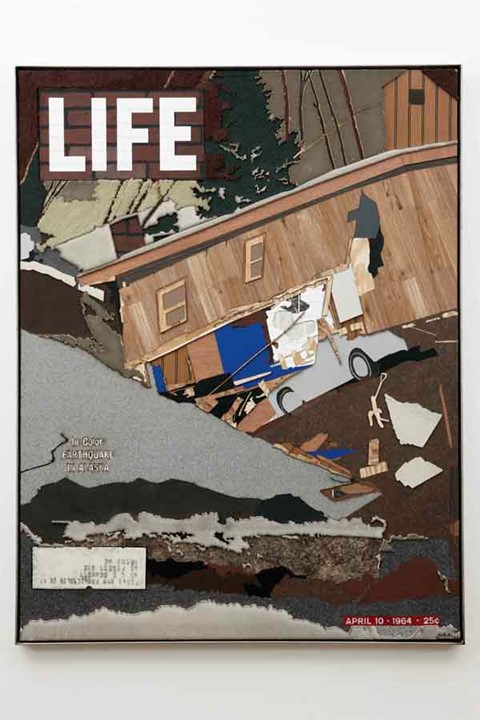

The last solo exhibition Matthew Day Jackson held in London was a photographic series of anthropomorphic rock formations found across the continental United States in the course of a three-month road trip in 2006. Inspired by the Native American myth of a disapproving Mother Nature rising up to reclaim the Earth, he titled the work The Lower 48. Since then, through sculpture, collage, video and photography, 37-year-old Day Jackson has been exploring the mysticism of machinery, materials such as skulls, skeletons, and geodesic domes and their symbolism in utopian thought, gaining a reputation as one of the most relevant, and inventive artists of his generation. His latest London solo show, Everything Leads to Another, takes a panoptical view of our recent history, revisiting and revealing the forces that have come to characterise our present through making connections between such culturally loaded forms. Such as a reclaimed B29 cockpit – the pressurised plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – filled with anthropological and archaeological curiosities as a modern Noah’s Ark of sorts, juxtaposed with a large, Drywall multi-panelled landscape of the moon in the format of Monet’s Reflections of Clouds on the Water-Lily Pond, and re-imagined LIFE magazine covers from the Atomic Age of the 50s and 60s. Here, the American artist discusses the beauty in collaboration, the drive to create brave new worlds, and the processes and motivations behind his current show.

Can you talk about your practice and your intentions as an artist?

I think that as an artist I’m trying to explore all the possibilities of how I can express myself. Most of the time it's sculpture – but also through smell, taste, sight and sound. As you experience all these senses, I don’t understand why as an artist I should be distilling them down to one particular medium or methodology. I naturally think up songs as I work, so I’m not trying to expand, I’m just trying to become clearer in how I believe art should be made, what I believe art should be, how we should think about art. And in that process I include as many of my friends, and as much of my person as I possibly can – because I’m only here once, and who knows how long that will be. It sounds a bit romantic, maybe even a little melodramatic but tomorrow is not a guarantee, you only have now. In terms of making music, it’s a part of me. I’ve sung longer than I’ve made art, I like to dance a lot, and so why shouldn’t that be a part of what I do? Particularly because the way that I talk about materiality, and the way that I talk about the figure in sculpture and how we’re not just flesh and bone, but as you wake up in the morning and brush your teeth and comb your hair and choose the shirt that you’re going to put on your back, you’re sort of hiding the things that are deep inside of you. Because what you do is you’re going out and advertising to the world what you’d like to be. Perhaps it’s not necessarily what you are, and so, sculpture works in the same way.

Why, today, are you interested in August 6 1945, the day the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima?

In terms of the understanding of August 6, I’ve come at it through trying to understand Robert Oppenheimer, and I’ve found myself drawn to NASA, the Manhattan Project, the Center for Advance Study at Princeton, just as I am with abstract expressionists in New York. There’s a certain drive in that I find attractive, the beauty in collaboration – a team of people working together in trying to accomplish something that’s no one has ever seen before. And this is where I’ve come to try to understand certain moments in history. Hiroshima defies understanding, but you can recognise the bankruptcy of it all and how much of my life is predicated on it. In Hiroshima’s subsequent birth of the Nuclear society and family, and you could also argue, the internet, and the way that we understand each other – the nuclear weapon was more effective in creating a cohesive humanity and understanding with one another way more so than the hippy movement could have ever dreamed. But not through love, but in the ability to kill with impunity, without borders – there’s no edge to a nuclear explosion. It never goes away. And in trying to and how I understand Hiroshima, it affects the kind of sculpture that I make.

Does making art fulfil some sort of personal quest?

Absolutely. I'll totally admit that art is therapy – all art is a self-portrait, and all those cheesy things that aren’t cool. Yet also, with the B29 bomber, in learning that it was the most money America had ever spent – we spent more money on the B29 than we ever did on the Manhattan Project – that’s one thing. But also at the same time, this first light (the light from the explosion in Hiroshima) from the bomb detonated 1000 foot above ground, the flash of white light that nobody had every seen before was terrifying, and the pilot, Paul Tibbits’ sees the birth of a brand new world over his shoulder, which is why I have called the sculpture Axis Mundi – a spiritual sign, which depending on what you believe, is different for everyone. To fracture the atom, to create fission is in a sort of way a laugh in the way of God, in that the way we understand our world is drawn from the light that reflects off these base elements. Also, I don’t really edit where I go. Next year, I’m going to be racing a drag-car for a feature film we’re shooting.

You have been making these annual self-portraits, as a corpse in a coffin, a skeleton, or geometric blocks representing parts of your body – do these represent some sort of ritual self-cleansing?

Maybe, that’s where my ideas drag me I guess. I recognized when I was younger there was no real place for me, I couldn’t paint for example, I just found it too hard. Like how I recognised I could never be Goya or Velazquez, so I just gave it up. It’s a number of things. When I had my son I recognised there was a certain part of who I am that needed to be killed off, to purposefully undergo a change, or say when your voice breaks, it’s like a mini-death, a transformation. At the very end of the project there’ll be a picture of me dead, so maybe I never died! The lengths I go to make these pieces is kind of hilarious.

Everything Leads To AnOther by Matthew Day Jackson runs at Hauser & Wirth London, Savile Row until July 30 2011.

Text by Xerxes Cook