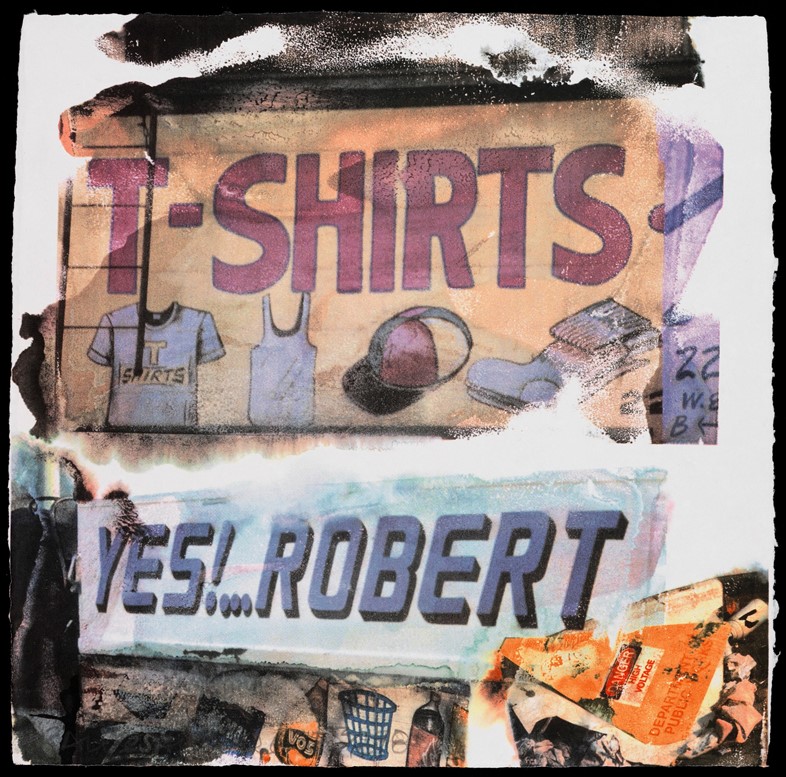

Seven things you might not know about the artist who rebelled against Josef Albers and worked in a department store with Andy Warhol

Born in Texas, brought up by Fundamentalist Christians and trained as a pharmacist, Robert Rauschenberg would go on to be one of the most radical and innovative artists of the 20th century. A pioneer of what would later be called the ‘hipster aesthetic’, during the 1950s Rauschenberg rented studio apartments in formerly industrial districts of downtown New York City. And, in responding to post-war ‘material excess’ by incorporating into his work everyday objects and ‘trash’, Rauschenberg was described by artist Jasper Johns as “inventing the most since Picasso”.

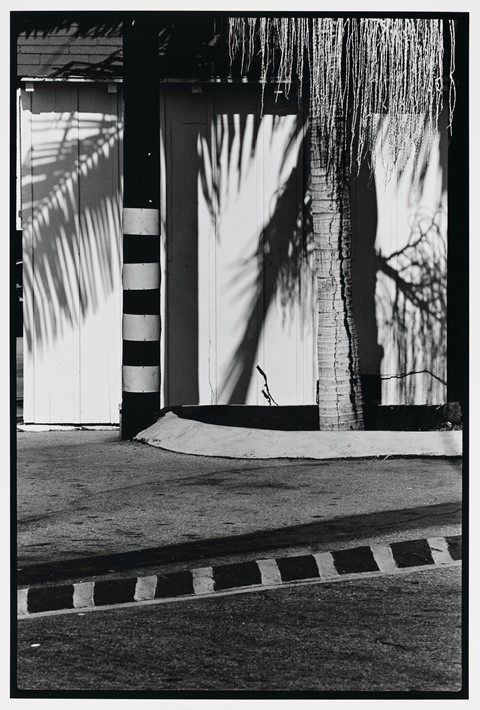

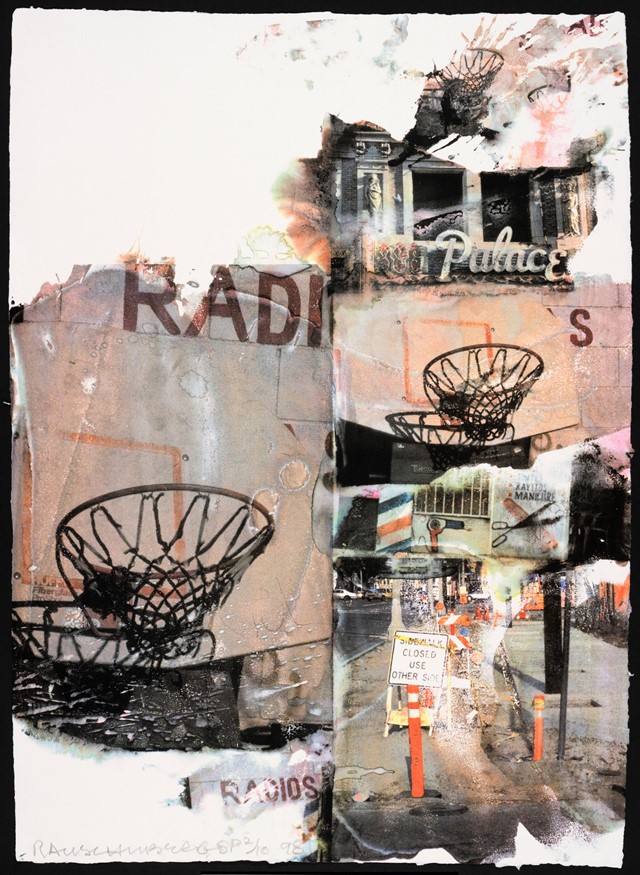

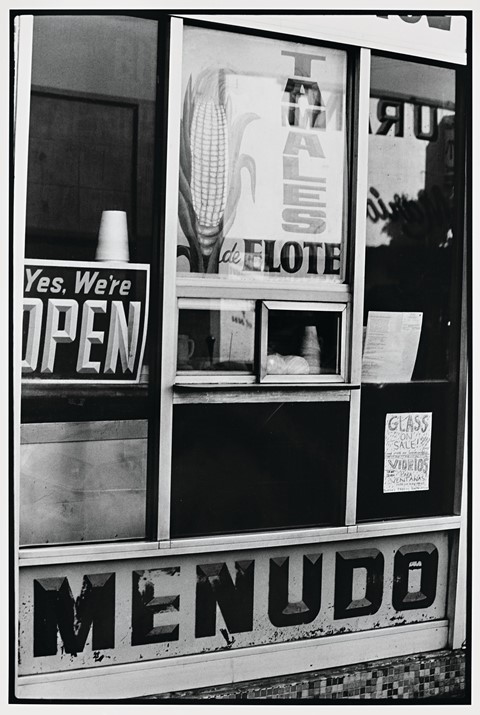

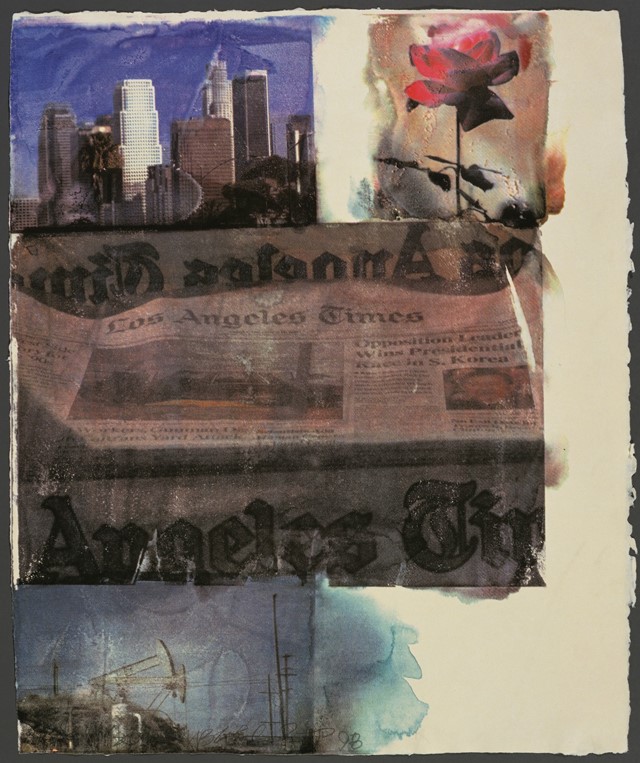

Now, on the ten-year anniversary of the artist Robert Rauschenberg’s death – and to coincide with a new exhibition, Rauschenberg: In and About LA at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – seven little-known facts about one of the twentieth century’s most important artists.

1. He served in the US Navy

After the bombing of Pearl Harbour and America’s joining of the Second World War, 19-year-old Rauschenberg was drafted into the US Navy. Refusing to kill, he was soon put to work as a psychiatric technician in a naval hospital near San Diego. Four years of war solidified his pacifist instincts and resolved Rauschenberg to become an artist. After being ‘demobbed’ he worked briefly as a newspaper illustrator in Los Angeles, before the so-called GI Bill provided the funding in 1948 for six months study in Paris at the prestigious Académie Julian. Keen to continue his studies on return to the United States, Rauschenberg attended the ‘experimental’ Black Mountain College in North Carolina and, later, the renowned Art Students League of New York.

2. He had relationships with men

Rauschenberg’s sexuality is often deliberately ignored or downplayed by curators and critics, in part because – living as he did in hostile times – he didn’t wish to publicly discuss it or, indeed, be judged because of it. It’s important to remember, however, that Rauschenberg’s artistic development, at least during the 1950s, was intimately intertwined with his romantic life. Married for two years to the American artist Susan Weill, shortly before the birth of their son Christopher in 1951, Rauschenberg met the artist Cy Twombly who would soon become his lover. The following summer he and Twombly travelled to Rome where they would remain for six months. A year later Rauschenberg was introduced to the artist (and Korean War veteran) Jasper Johns – a meeting that would herald perhaps the most formative romantic and artist partnership of his life. In 1955, Rauschenberg and Johns moved in together and, for the next seven years, became a highly productive couple. Later, during the last 25 years of his life, Rauschenberg would live happily in Florida with the artist Darryl Pottorf.

3. He rebelled against his teacher, Bauhaus pioneer Josef Albers

Artists are often fortunate in their teachers – if nothing else because they can, unwittingly, teach precisely what needs rejecting. In Rauschenberg’s case, he was taught by, and rebelled against, the artist Josef Albers. As a professor at the influential Bauhaus art school in Weimar Germany, Albers was forced to flee Nazi Germany in 1933. Emigrating to the United States, he became head of painting at the radical Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Here – right at the very end of his career – Albers would teach the young Rauschenberg, fresh from Paris. 60-year-old Albers’ pure geometric forms and uniform colours proved too rigid and old fashioned for the idealistic 23 year old. Soon Rauschenberg would discover a new, and specifically American, form of dynamic Expressionism.

4. His department store colleague Andy Warhol called him the “Staple-Gun Queen”

In 1951 Rauschenberg was fortunate enough to be taken on as a freelance window display designer by the historic New York City department store Bonwit Teller. That same year he was joined by Andy Warhol, and a few years later by Jasper Johns. A friendly rivalry arose that was marked – particularly after Rauschenberg and Johns became a couple – by Warhol’s ironic dismissal of them both as mere “staple-gun queens”. Bonwit Teller, however, proved the ideal place for all three to cut their artistic teeth. The ornate Fifth Avenue building (demolished 30 years later by Donald Trump) and its vast window spaces showcased some of the earliest examples of Pop Art, produced initially as ‘displays’. They included Johns’ first flag painting, Rauschenberg’s red paintings and Warhol’s Superman. Evoking a sophisticated sensibility described by the critic Susan Sontag in her famous 1963 essay Notes on Camp, the first Postmodern art movement was – in many ways and at least in the US – radically queer from day one. Unknowingly, staidly genteel shoppers bustled past the first showcasing of American Pop Art that would, within a decade, garner all three artists extraordinary levels of both critical success and popular fame.

5. He worked as a cleaner

You never know where things will lead – or when doors will open; but being in the right place at the right time often helps. Strapped for cash and in need of a job after returning from Rome with Cy Twombly, during the summer of 1953 Rauschenberg became a cleaner and handyman at the newly opened Stable Gallery in New York City’s Midtown. It proved to be a propitious move: soon he was befriended by the gallery’s owner, influential art dealer Eleanor Ward – herself recently returned from several years working for Christian Dior in Paris – who immediately offered him (along with Twombly) a joint exhibition that September.

6. He had Christmas lunch with his hero, Marcel Duchamp

It’s impossible to overestimate the influence of Dada artist Marcel Duchamp on the work of 20th century avant-garde artists. Duchamp denied any distinction between ‘art’ and ‘life’, and produced work that blurred those, and many other, conceptual categories. For Rauschenberg, who similarly tried to “act in the gap between the two”, Duchamp was a hero. Rauschenberg’s symbolic erasing (and subsequent framing) in 1953 of a drawing by artist Willem de Kooning is just one example of how Rauschenberg continued Duchamp’s provocative irreverence. The following year, again demonstrating Duchamp’s legacy (and too skint to buy art materials), Rauschenberg scoured the streets for discarded items he could incorporate into his work, resulting in his now-famous ‘combines’. Rauschenberg must have been thrilled to read a 1959 press interview with Duchamp in which the old man mentions his work. That Christmas, Duchamp and his wife sought out Rauschenberg and Johns, visiting their Downtown studio apartment, all four enjoying Christmas day lunch in nearby Chinatown.

7. He was also a set designer, choreographer and dancer

Interested in the “total work of art”, Rauschenberg was always an advocate for collaboration across artistic fields. Yet it’s a little-known fact that – beside being a painter, collagist, photographer, printer and sculptor – Rauschenberg was also a theatrical set and costume designer, a choreographer of dance and an experimental performer in his own right. His first collaboration occurred in 1955, and developed in tandem with an exhibition of his work at New York City’s Egan Gallery. Rauschenberg’s friend and neighbour, the composer Morton Feldman, produced a musical accompaniment (later known as the Morton Feldman Concert with Paintings) to be played in the gallery alongside his work. That same year Rauschenberg began designing sets and costumes for dancer Paul Taylor’s New York City theatrical performance of Circus Polka, and for choreographer Merce Cunningham’s dance performance of Springweather and People in upstate New York. During the 1960s Rauschenberg would go on to develop a series of vibrant artistic ‘happenings’ – enmeshed in their cultural ‘moment’ – by choreographing collaborations that included movement performances of his own. In Shot Put (1964), one of his most expressive works, Rauschenberg “drew with light” by dancing in a darkened room with a flashlight attached to his right ankle.

Rauschenberg: In and About LA is on show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art until February 10, 2019.