Parties have always been a hotbed for naughty behaviour and fashionable show-offs. As such, party photography remains an essential document of what we wear, how we blow off steam, and how social etiquette has changed with each decade.

In the 1970s, Village Voice’s Bill Bernstein captured the vibrancy of the New York disco years, pointing his lens towards diehard dancefloor regulars, rather than just the widely photographed fleeting appearances of peacocking celebrities at Studio 54. He gave us a rich record of what New Yorkers did after their nine to five, when it felt like the world was falling apart. Just a decade earlier, American documentary photographer Elliott Erwitt had immortalised on film the era’s relaxing of social barriers with the unlikely coming together of princesses, poets, society queens, celebrities and media moguls at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball in 1966.

“A lot of dramas and important moments in people’s lives happen during parties,” says photographer Dafydd Jones, who has captured British high society knees-ups, debutantes pushed fully clothed into lily ponds, and young and sloppy drunken snogs for over 35 years. He worked with Tina Brown during her time as editor at both Tatler and Vanity Fair, and a new exhibition of his exuberant black and white portraits are currently on display in Dafydd Jones: The Last Hurrah, at The Photographers’ Gallery.

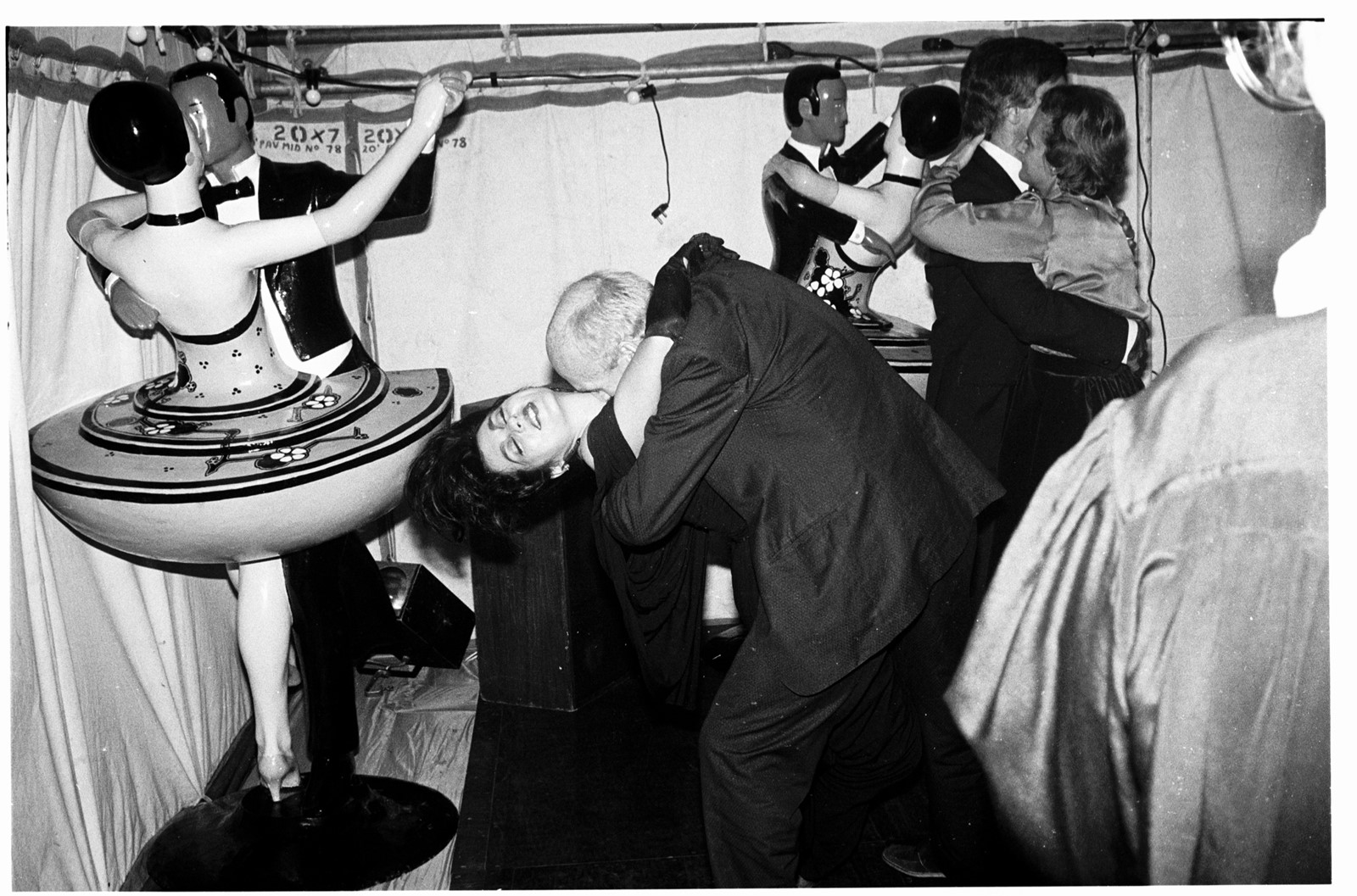

Armed with a discreet camera and a dinner jacket to blend in, Jones, who was living in Oxford at the time, photographed a mischievous slice of young society who were emboldened by the political mood of the day; Thatcher had steadily slashed tax rates for the rich since 1979, and Princess Diana was the most photographed woman in Britain. Hippies were out, and ‘Hooray Henries and Henriettas’ were in. “There was a boom,” Jones explains. “They were living in a bubble. It was cool to be wearing black tie and dressing up in reaction against the relaxed style which had gone before in the 70s.”

Jones’ first assignment for Tatler was in 1981; Tina Brown sent him to The Grand Military Gold Cup at Sandown Park Racecourse in Surrey where Lady Diana Spencer, still in her dowdy pie-crust collar and wool skirt phase, was the centre of attention following her recent engagement to Prince Charles. Jones hung back to get an eerily prophetic wide shot of Diana dwarfed by curious onlookers peering from the stands, and half of Fleet Street’s photographers all competing for the money shot. It also got him more freelance work from Brown, during a time when she was reshaping Tatler from an outdated high society rag to a ritzy glossy. “Everyone loved working for Tina,” says Jones, “We were all bereft when she left Tatler in 1983.”

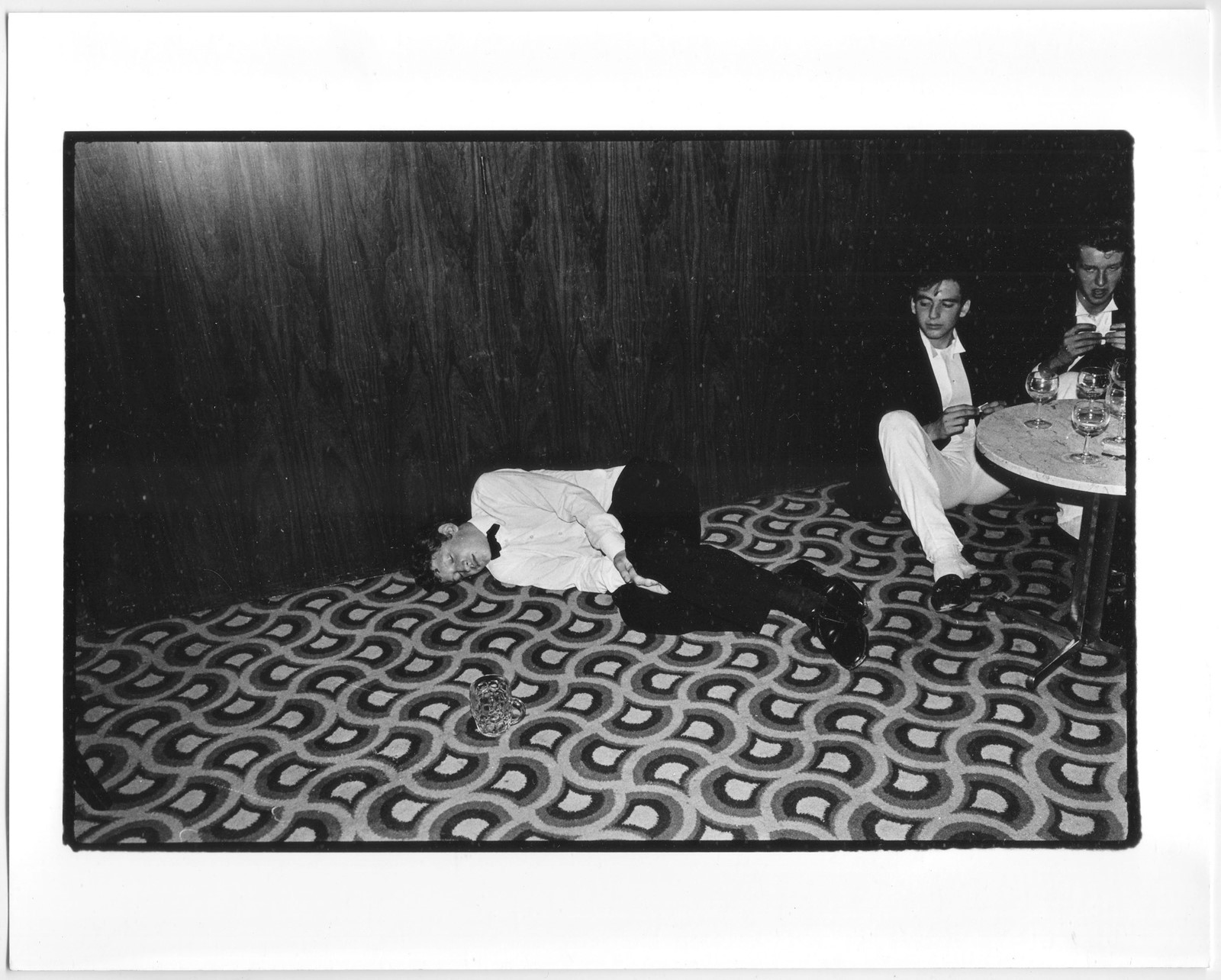

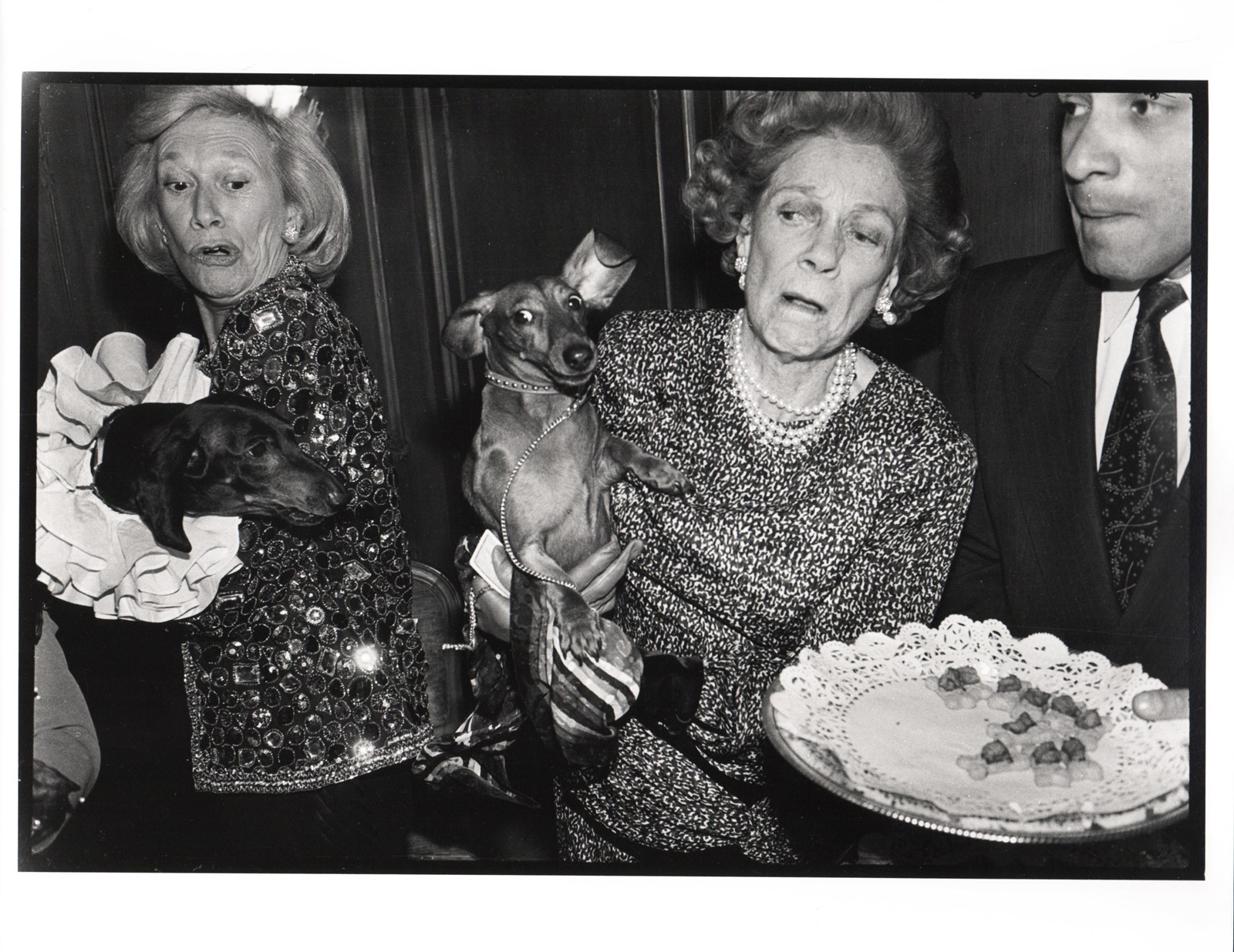

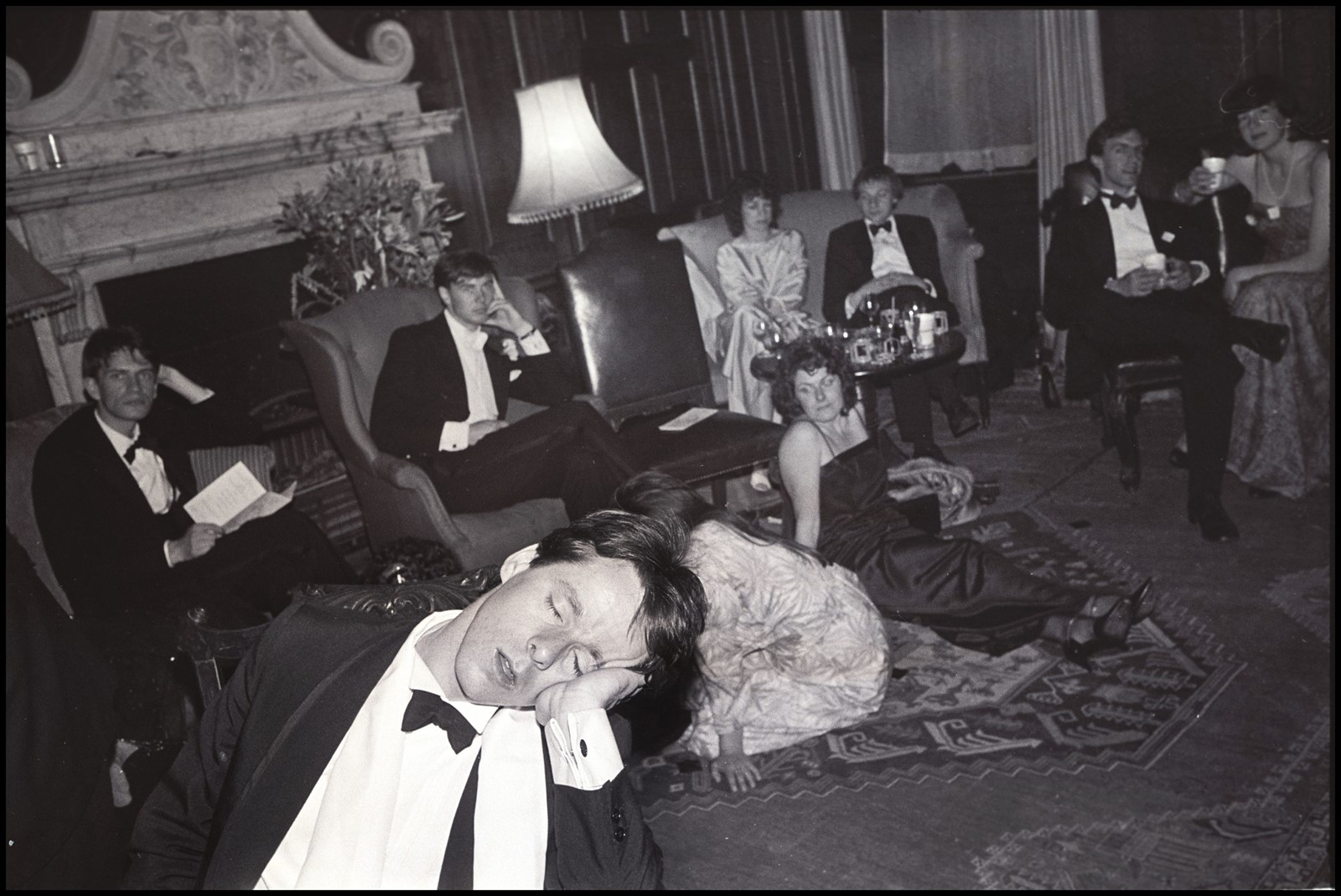

Inspired by the striking works of Don McCullin, Martin Parr’s photographic wit, and German photojournalist Erich Salomon (Jones’ long-running Sleepers series has echoes of Salomon’s famous 1930 portrait The Hague, which captured an exhausted statesman falling asleep after a day of negotiations), Jones went on to snap exuberant, mesmerising portraits of fallen partygoers sleeping on the lawns in their ballgowns and coiffured society queens with squabbling lapdogs.

At first, Tina Brown used to complain that he was photographing too many unknown Sloanes, according to Jones. “I think ideally she wanted pictures of a kind of literary intelligentsia,” he says. But after a news story about an Oxford dining club trashing a restaurant broke, she reacted quickly, printing a feature of Jones’ work that celebrated the Hooray Henries of the day. “Tina was very direct. Always competitive. She’d say so if she didn’t like your work. And if she saw another photographer at a party, she’d get their details and ask them to come into the office.”

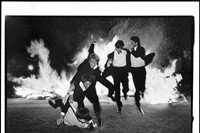

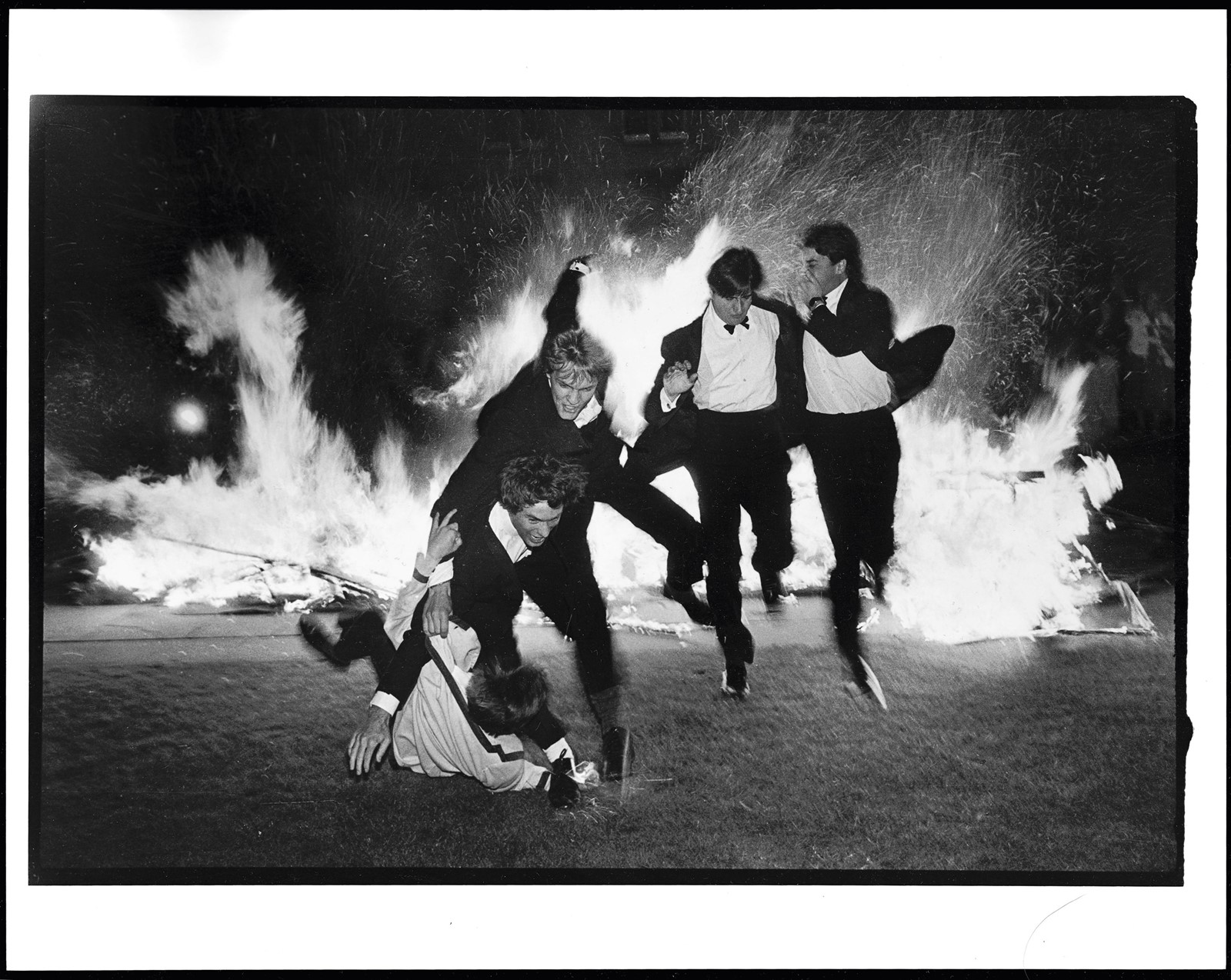

Five students hot-footing it away from a burning boat in the quad of Oriel College, Oxford is one of the most arresting photographs in The Last Hurrah. The high flames, which look straight out of a film set, are incongruous in a collegiate setting. But they bring to mind a longstanding tradition of the carefree upper classes causing havoc; from the infamous and often callous initiation tests of the Bullingdon Club, to the gratuitous chaos being caused by its alumni in British politics today. In that respect, The Last Hurrah is a timely reminder of the decadent annual traditions so beloved by Oxbridge students, making the calling of the EU referendum by the Conservatives, and subsequently Brexit, look like just another inconsequential way to pass the time, like jumping into a pool, thrashing opponents in a boat race, or being elected President of the Union. The London gallerist Chris Beetles recently told Jones that his photographs were fantastic, but there was just one problem: he couldn’t stand the people in them.

“Perhaps the British don’t hate the upper classes as strongly today,” Jones considers. “Now they view their eccentricity with more affection.” He cites the recent success of Patrick Melrose, the television mini-series adaptation of Edward St Aubyn’s novels about the British upper classes, and notes the new international monied crowd which has “taken over central London”.

Regardless of whether you find the subjects charming or charmless, you’re sure to appreciate Jones’s portraits as a record of when parties were simply better than they are today. With no smart phones, you could awaken the day after a party with a head-splitting hangover, but none of the accountability of an Instagram story of you on the dancefloor. You might actually talk to people in the queue for the toilets. And if you didn’t fancy that, you could retreat into your own world beneath a pile of coats or furniture.

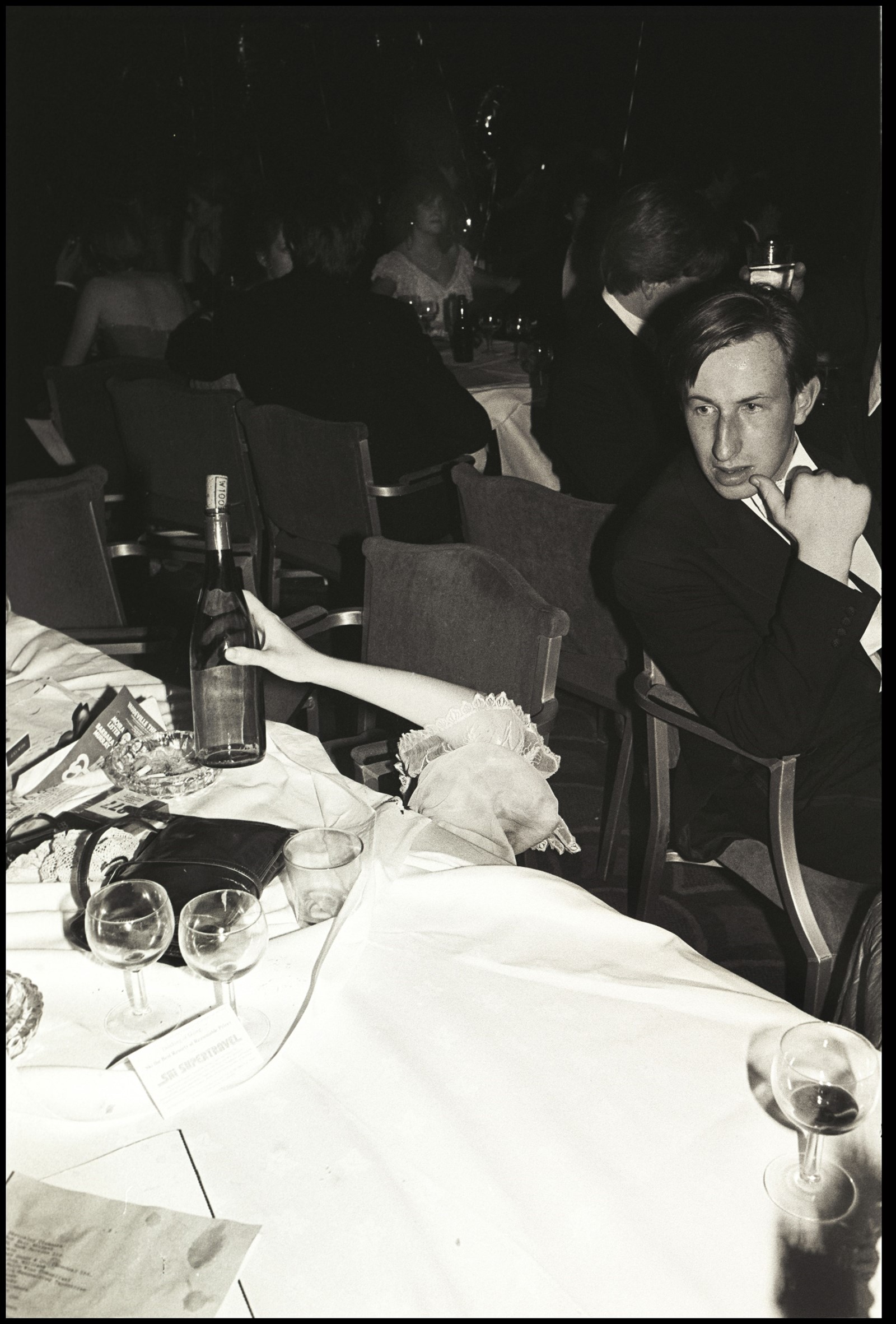

Henrietta Thompson’s Hand, a photograph taken at the Falklands Ball at Grosvenor House in Mayfair in 1982, shows a hand mysteriously snaking out from under a white cotton tablecloth, apparently to steal a bottle of red from the table top. It’s one of Jones’ favourites: “One minute I was photographing a couple kissing nearby, and then I noticed this arm appearing from under the table. Afterwards a girl wearing sunglasses popped out from underneath.” He adds: “I don’t know for sure what was going on, but there’s a story there.”

These days the equivalent knees-ups are more stoic affairs. Jones remembers a recent Oxford University May Ball at Worcester College: “There were noise restrictions, so everyone was in a silent disco tent, listening to their own music. There was lots of photo-taking with phones, and it was more restrained and self-conscious than it would have been 25 years earlier.” The scene made for surreal photographs, Jones notes, but there was noticeably less interaction between guests. The Last Hurrah is a jolly call to counteract all that and loosen up a little. Jump into a pool, smear your lipstick, or at the very least start a wilder party under the table.

Dafydd Jones: The Last Hurrah is on show at The Photographers’ Gallery until September 8, 2018, and the book of same name is out now, published by STANLEY/BARKER.