On the anniversary of its protagonist Ingrid Bergman’s birth, we look at Spellbound’s Surrealism

Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound was a film originally conceived as a favour of sorts to producer David O. Selznick. Hitchcock and Selznick had had contract disagreements, and the making of Spellbound was largely due to the latter’s enthusiasm: the producer wanted to make a film that promoted psychoanalysis, having experienced its benefits himself, and put a great deal of money behind the project when Hitchcock showed interest in buying the film rights to The House of Dr Edwardes, the 1927 novel on which the film is based.

In it, Ingrid Bergman plays the psychoanalyst Dr Constance Peterson, the only female doctor at Vermont asylum Green Manors. “Your lack of human and emotional experience is bad for you as a doctor – and fatal for you as a woman,” Dr Murchison, the hospital’s soon-to-be retired director, says to Peterson in the film’s first ten minutes, hinting at his and his colleagues’ fascination with her cool professionalism and apparent lack of emotion. Peterson is sharp and stoic, and headstrong when it comes to rejecting the advances of both patients and doctors at Green Manors.

It’s Bergman’s character who drives the film, as she embarks on a journey with a man who calls himself Dr Anthony Edwardes – played by Gregory Peck – but who later turns out to be John Ballantyne. Ballantyne suffers from dissociative amnesia: he cannot remember who he is, or why he poses as Dr Edwardes, but believes himself to be guilty of Edwardes’ murder. Running from the law and towards uncovering the truth about Edwardes’ death, Peterson coaxes the events from Ballantyne’s mind by analysing his dreams and studying his behaviour. The two have fallen in love, but she sees him as her patient and takes responsibility for “curing” him – which she eventually does, after also solving the mystery of Edwardes’ murder. In Spellbound, typical tropes of Golden Age-era Hollywood are subverted; Ballantyne is the beautiful but distressed man, in need of being saved by his female doctor.

Spellbound was a success upon its release in 1945, despite its notoriously stifled production (and scandalous: Bergman and Peck had an affair during filming, while both were married to other people). Hitchcock and Selznick each had their own experts on hand to aid filming. Selznick had hired Dr May Romm – his own therapist – as the film’s technical advisor. When it came to the specifics of psychoanalysis, however, Hitchcock was less concerned with technicalities than Romm, and if she would offer her opinion, the director would purportedly tell her, “my dear, it’s only a movie”.

In turn, Selznick pushed back against Hitchcock’s hiring of Salvador Dalí to construct a dream sequence for the film. In fact, the producer had only agreed to Dalí because of the potential publicity spike, and would eventually bring in production designer William Cameron Menzies to direct the sequence while Hitchcock was away. The section of the film was to depict Ballantyne’s dream, which Peterson and her mentor Dr Brulov analyse in order to recover Ballantyne’s memories. Dalí and Hitchcock came up with an elaborate and, unsurprisingly, surreal 20-minute-long dream sequence that takes place at first in a gambling house and then on a rooftop in a forest-like setting, and at times apparently featured Bergman playing the goddess Diana in a ballroom with pianos suspended from the ceiling (images exist of Bergman in a draped costume, like a work of classical sculpture). Selznick, however, deemed the section too complex to be included, and cut the footage to just two minutes. Hitchcock later said that “what I was after was the vividness of dreams. As you know, all Dalí’s work is very solid, very sharp, with very long perspectives, black shadows. This was again the avoidance of the cliché: all dreams in movies are blurred. It isn’t true – Dalí was the best man to do the dreams because that’s what dreams should be.”

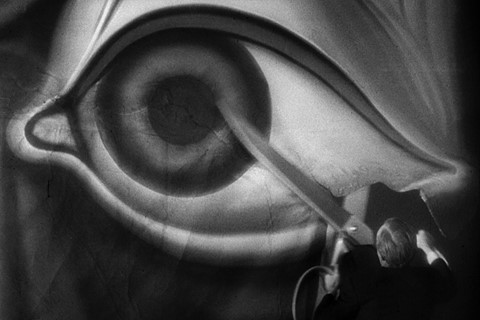

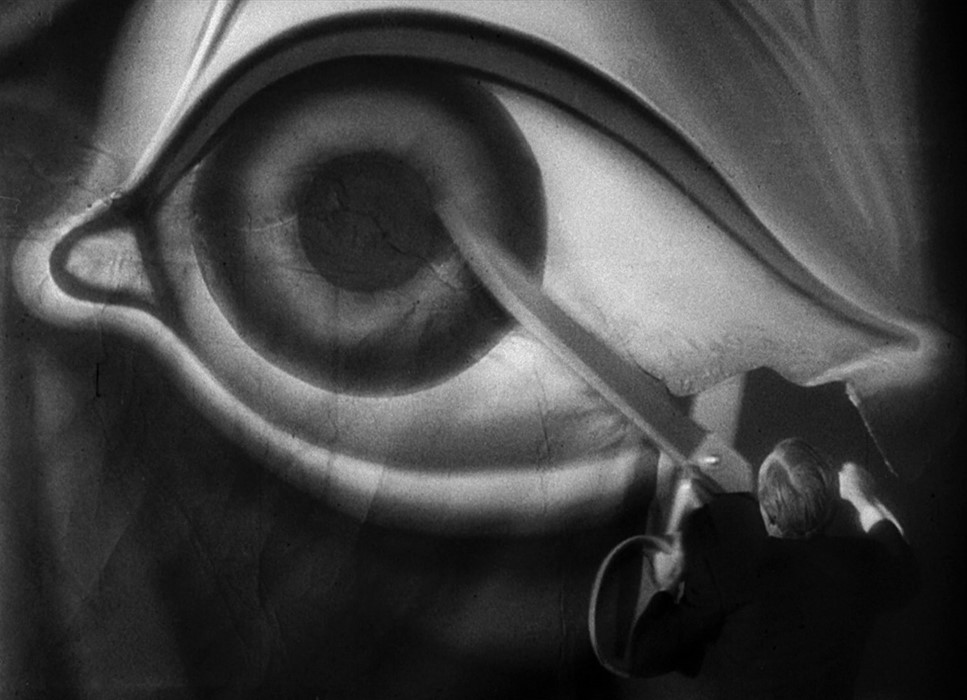

“But Dalí had some strange ideas; he wanted a statue to crack like a shell falling apart, with ants crawling all over it, and underneath, there would be Ingrid Bergman, covered by the ants! It just wasn’t possible,” Hitchcock said to François Truffaut in 1962. “My idea was to shoot the Dalí dream scenes in the open air so that the whole thing, photographed in real sunshine, would be terribly sharp. I was very keen on that idea, but the producers were concerned about the expense. So we shot the dream in the studios.” The clips that appear in Spellbound are suitably unusual, and make for suspenseful viewing. In a “gambling house” (he thinks) Ballantyne sits playing Blackjack opposite men with masked faces and blank cards, and the walls are covered with painted eyes, though these curtains are being cut in half by a man and a very large pair of scissors. When the next section appears, tree roots grow out of the chimney on a rooftop, and a rocky cliffside in the background takes the form of a man’s evil-looking face. In the film, the few minutes of Dalí interrupt the scientific, logic-based focus of the rest of its plot to offer an unforgettable and daring piece of cinema – and, ironically, one can only dream of what the 15-or-so minutes of cut footage looked like.