Frida Kahlo is looking into a mirror. She is wearing a black and white blouse and a long black skirt, with her hair plaited and piled high. We see both her and her reflection – the two Fridas. This is just one in a series of portraits of the artist, taken in 1944 by her friend Lola Álvarez Bravo, Mexico’s first female photographer. What these images of Kahlo in her garden capture so clearly is the very nature of the artist’s relationship with the wider world: us looking at Frida, looking at herself.

“I was almost thinking of her painting, The Two Fridas, when I photographed her,” Álvarez Bravo recalled. “With the landscape behind her in the reflection, it seems as though there really is another person behind the mirror.”

Nearly 65 years after Frida Kahlo’s death, the idea of two Fridas is one that persists. Kahlo, who was as radical in the flesh as in the highly charged, dream-like paintings she mined from the highs and lows of her life, constantly played with the boundaries between her public and private self. But while her paintings offer an unflinching look at her personal experiences, a number of photographs show another side to Kahlo – a side not revealed in her self-portraits, which make up about a third of her paintings.

Through the work of a contingent of female photographers, we meet another Frida. Lola Álvarez Bravo, Gisèle Freund, Lucienne Bloch, Toni Frissell and Imogen Cunningham found both a charismatic subject and a willing collaborator in Kahlo. Between them, they created some of the most intimate and compelling portraits of the artist at pivotal moments in her adult life. Compared to the very still, stylised way she depicts herself, through their eyes she appears softer, more playful, at times fragile, but always subversive.

“Kahlo was very enigmatic, mysterious and beautiful, and I think this is what captured the imaginations of not only many male photographers, but also female photographers,” says Circe Henestrosa, co-curator of Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up, an ongoing exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London that looks at Kahlo’s self-invention through her most personal belongings. Of the 96 photographs of Kahlo on display, 31 were taken by female photographers.

“I think there’s a difference in the way these women were looking at her,” explains Henestrosa. “We chose these photographs because of their honesty; they are more personal in a way, somehow more delicate.” She notes that all the photographs in the gallery focused on Kahlo’s lifelong home, the Casa Azul, are the work of a select few women.

“There’s a sensitivity that these photographers bring to the exhibition, which is about Frida Kahlo’s portrayal, but also about a collaboration between these women,” adds Ana Baeza Ruiz, who assisted Henestrosa and co-curator Claire Wilcox with the exhibition’s research. “There’s a way in which the photographs are a form of portraiture, but they’re also a form of performance that starts with Kahlo herself.”

It was during her time in the US between 1930 and 1933 that Kahlo began attracting international attention as the head-turning young wife of muralist Diego Rivera. In her modern take on traditional Tehuana dress, she was unlike anything the people of San Francisco, Detroit or New York had seen. In San Francisco, she met Imogen Cunningham, one of the first professional female photographers in America, and in New York, Swiss-born Lucienne Bloch, an artist with an eye for photography.

“I hate you” were the first words Kahlo said to Bloch, who was seated next to Rivera at a party hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Rivera was a notorious philanderer, but when Kahlo realised Bloch had no designs on her husband, she found a companion in the young artist. Bloch soon became Rivera’s assistant and Kahlo’s friend. Her candid shots of Kahlo laughing, winking and biting her necklace are revelatory, and she is responsible for the iconic image of Kahlo at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel in 1933.

After Kahlo’s return to Mexico, pioneering fashion photographer Toni Frissell took her portrait for a feature in American Vogue titled Señoras of Mexico. Later, some of the most poignant photographs of the artist were taken at her home in Mexico City, where she spent more and more time due to the disabling effects of a life-altering tram accident in her youth. Into this lively space, filled with exotic plants, pre-Columbian artifacts and seven hairless Xolotl dogs, Kahlo welcomed a procession of visiting artists, writers, architects, politicians and photographers, such as Lola Álvarez Bravo and Gisèle Freund.

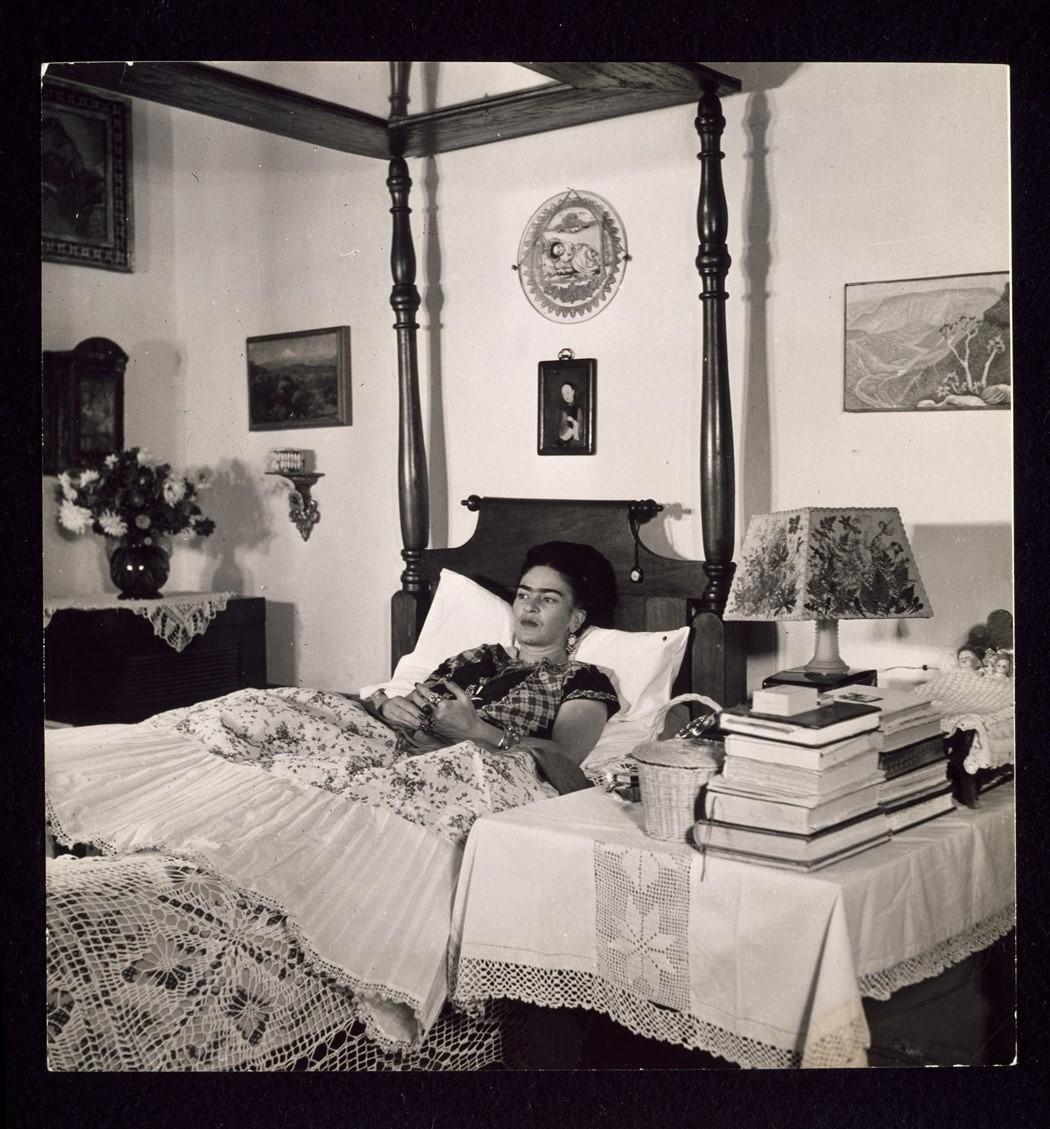

Álvarez Bravo was a protagonist in what writer Anita Brenner called the ‘Mexican Renaissance’. Her portraits of Kahlo are proof of a close friendship, which began when the two women met in 1922 and lasted until the painter’s untimely death in 1954. Over the years, Álvarez Bravo photographed Kahlo many times. She also ran her own gallery between 1951 and 1958, where she hosted Kahlo’s only solo show in Mexico during her lifetime, the year before the artist died. This was the exhibition that Kahlo, due to ill health, famously attended in her four-poster bed.

French photojournalist Gisèle Freund took some of the last photographs of Frida Kahlo. A founding member of Magnum Photos, she travelled to Mexico between 1950 and 1952, frequently visiting Kahlo and Rivera at home. As well as portraits of Kahlo in bed, at her easel or in her beloved garden, Freund documented the interior of the Casa Azul, including the artist’s desk and studio. “I always preferred photographing a person in his private space, among his belongings... And the decor of a home reflects the person who inhabits it,” she wrote in her memoir, The World and My Camera.

Kahlo was a sitter from a young age, and it was through the lens of her father’s camera that she first began to play with – and understand – the power of her own image. It is through the lens of these female photographers that we understand the power of her person. Because the remarkable thing about Frida Kahlo is not her striking appearance or her inimitable style, but her passionate humanity – so much so that when André Breton described Kahlo’s art as “a ribbon around a bomb”, he could have easily been talking about the artist herself.

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up runs until November 4, 2018, at the V&A, London.