In the beginning was the word, and the word was art – though rarely do we conflate the two. Image and text are largely considered distinct forms that have rendered their application as distinct disciplines. Invariably, though, artists traverse boundaries to question, examine, provoke, entertain, exalt or otherwise engage with new ideas.

The word in art, as art, is a realm all its own, one inhabited by the few who dare to delve into its depths. Visual Language, a bi-coastal group exhibition presented by Subliminal Projects, Los Angeles, and FACTION Art Projects, New York, celebrates the power of the word in art. Here, artists including Jenny Holzer, Guerrilla Girls, Betty Tomkins, Ed Ruscha, DFace and Shepard Fairey present their own take on the word, using it for a wide array of expression, be it political, ironic, poetic, typographic, abstract or conceptual.

Jenny Holzer is perhaps the most renowned and respected contemporary artist to use words as her métier. Hailing from Gallipolis, Ohio, Holzer arrived in New York City in 1976 at the age of 26, becoming an active member of Colab, the downtown artist collective that included Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, James Nares, Jane Dickson and John Ahearn, among others. Holzer gained early recognition with Truisms (1977–79), a series of epigrams she penned, printed and wheat-pasted as anonymous broadsheets on walls around Manhattan. Her gift for aphorisms was impeccable as she brought together poetry and pithy witticisms with a populist punch, making them available to the general public at a time when graffiti and street art was making its presence felt.

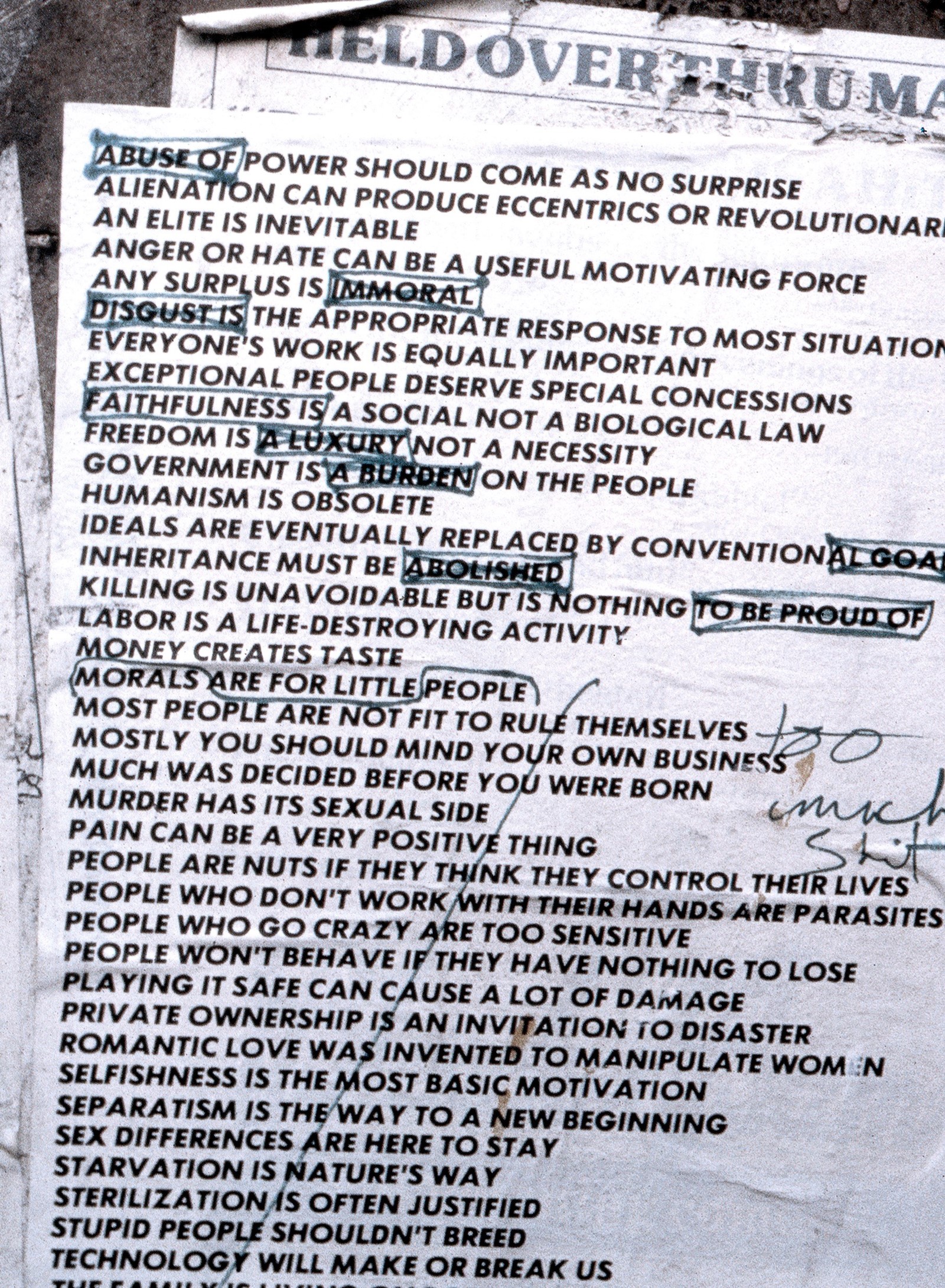

Over the past 40 years, Truisms have become among some of the best-loved and most enduring works of Word Art. Holzer sums up their popularity succinctly: “Clichés endure!” Then she laughs, as the impulse to protest the term ‘cliché’ suddenly occurs. “Abuse of power should come as no surprise,” the first line of a 1977 Truism, has enjoyed new life during the Trump administration. But as the piece goes on, Holzer’s words contain an intriguing mix of polemic, rationalisation, judgement, propaganda and spin. It becomes increasingly clear that the Truisms that resonate say more about the reader than the artist, exposing the fundamental connection between idea and identity the work provokes.

“With the Truisms, and subsequently the Inflammatory Essays and some other series, I had to assume a number of very different identities to be able to write them properly – especially since I am not really a writer. I have to use every tool available to me to make the text convincing,” Holzer reveals. “The purpose of writing so many distinct points of view was to question, ‘What do you do when these things are all around and there are individuals fervently saying each?’” We could consider that answer now in light of social media and the ways in which it has become a virtual environment for people to push their own Truisms. Like many on Twitter, Holzer first adopted the guise of anonymity in order to let her words speak independently of an identifiable messenger.

“I had worked in the streets anonymously for some time for various reasons including that I wasn’t sure I was an artist to start with, and so I felt outside was like Speakers’ Corner in the UK – you go out and offer what you have in the hopes that it is of interest and use to others. I used anonymity with the Truisms so that no one will attribute the sentences to a single 20-something female,” Holzer laughs. “When I was doing stuff in the street, it didn’t matter to me if anyone thought it was art – so maybe that has something to do with the reason that it worked. It didn’t have any art baggage necessarily, other than there were some precedents for those in the know.”

Holzer’s comfortable disregard for labeling herself as a writer and her willingness to make art without concern for how it would be perceived has kept her work fresh and energetic over the years. She freely experiments with form, finding the appropriate medium and location for the work, whether racing silent messages along an L.E.D. display board installed along the winding inner wall of the Guggenheim in her 1989 retrospective or coming up with a simple but effective solution to how to share her Inflammatory Essays (1979–1982).

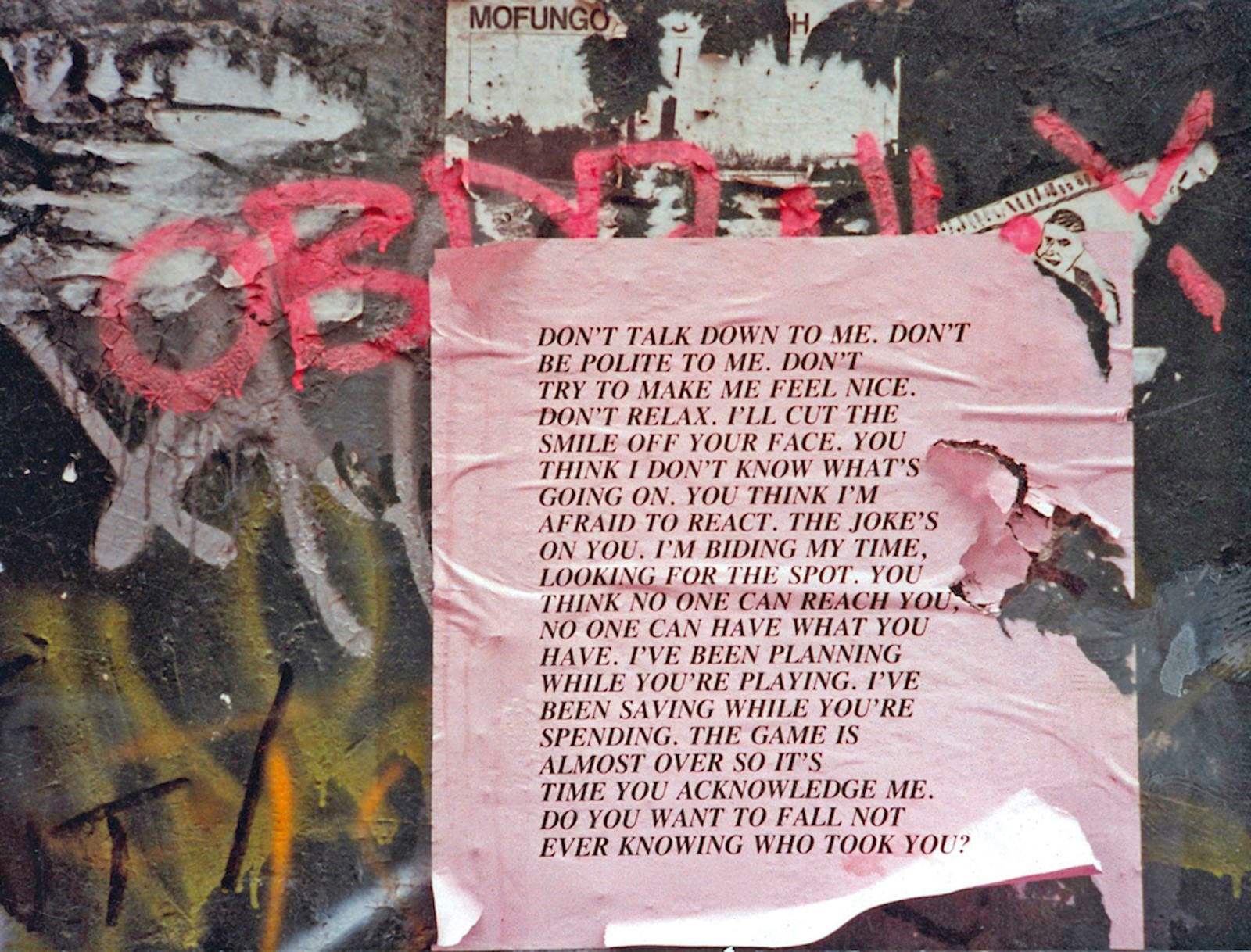

“I have experimented with a number of approaches. At times, the content will come first. It happened with the Truisms, for example. I had those and it was like, ‘Ooh, what do I have? It’s really no great long-form poem and it’s not a novel, so what do I do with this?’ And then I realised: black and white street poster – that would do the trick, because I wanted to offer content out of doors,” Holzer details.

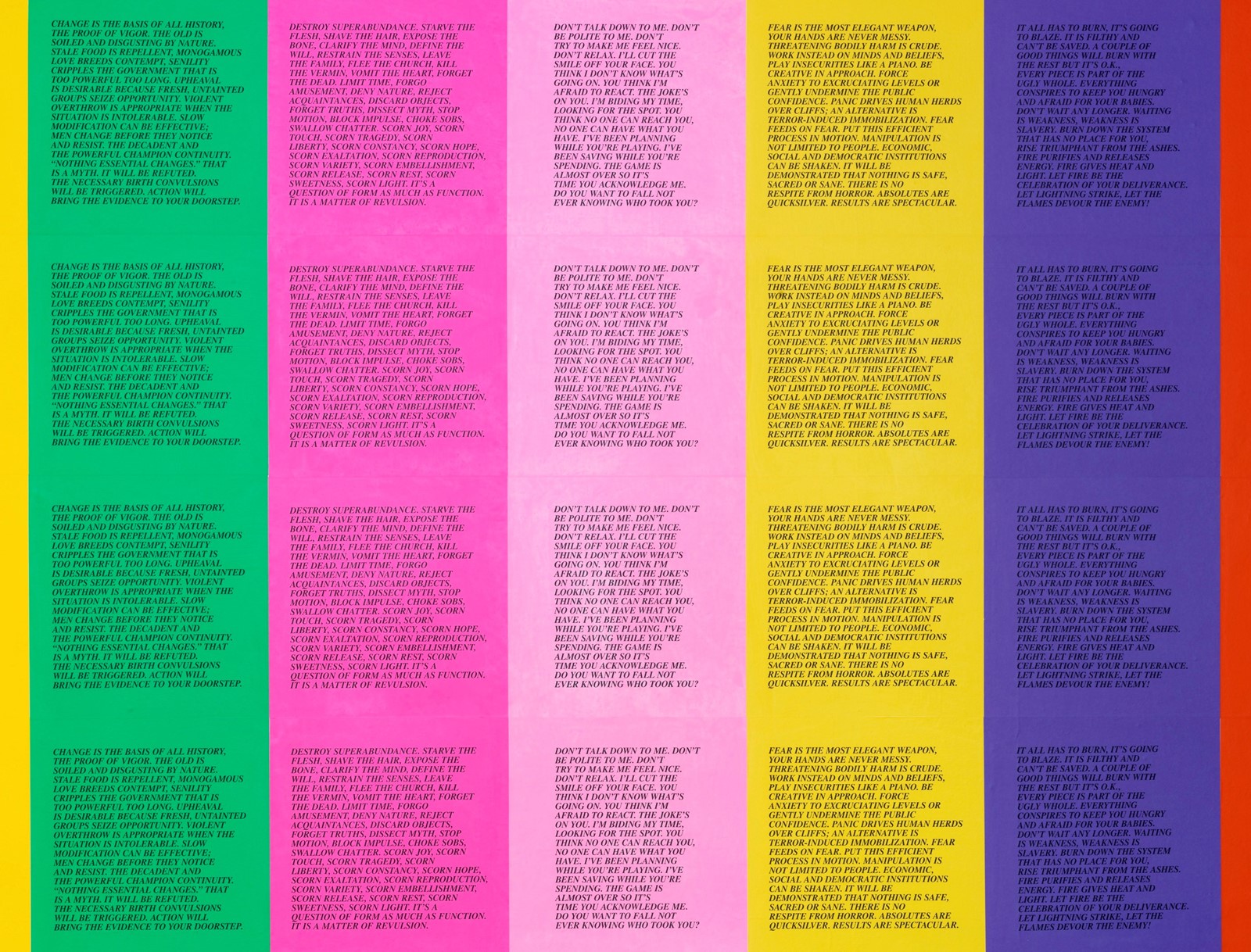

“With the Inflammatory Essays, I thought about form. I wanted them to be somewhat controlled so each was 20 lines and 100 words. I chose different colours because I wanted people to be alert to the fact that it was an old essay, not an old one in the street, so I had a pink essay, then a red one, then a blue one, then a green one. When I put all the essays together on big walls, it let me do some patterning and I did such in the hopes that this would catch people who otherwise might hurry by. More recently, I’ve liked projecting text so that they glide by on lovely surfaces and carry beauty, sorrow, rage or whatever they are meant to be carrying.”

Holzer’s ability to catch and capture the attention comes from her ability to navigate the space between image and text, transforming language into a visual spectacle and then holding fast with an idea that excites, confounds, or vexes. “I hope my version of the Truisms could be used to caution people about their use of clichés and perhaps raise things that matter to people,” Holzer notes. “Or when the conflicting sentences I put in my piece invite people to do a process of self-examination.”

In many ways, Word Art is the perfect genre for our times, as our culture continuously evolves with a host of competing narratives delivered in compelling new forms. Consider the rise of the meme and its dominance, or the instant impact of graffiti. Words ground us in something that is simultaneously abstract and tangible: the symbol of the idea made visible. “Language can communicate. There’s a trite but true announcement and for that reason could be accessible to an audience that’s not wholly familiar with art history (or nonsense),” Holzer says.

The works featured in Visual Language remind us that ideas, like canvases and sculptures, are constructions – though we may unwittingly forget this in a world where we are assailed by a never-ending stream of pictures and words that we must vet for ourselves.

Visual Language is on at Subliminal Projects, Los Angeles and FACTION Art Projects, New York until October 6, 2018.