These slow, private works in paint show a new and rarely seen side to the American photographer

On September 13, 1984, the first major retrospective of American photographer Irving Penn opened at the Museum of Modern Art. Penn, who had made his name elevating photography to the realm of fine art, worked tirelessly alongside John Szarkowski, director of the department of photography, to examine a massive body of work, making new prints for the show that he has never printed before.

While delving into his archives, Penn rediscovered early works on paper that he had made between 1939 and 1942, while he was a young illustrator working for Harper’s Bazaar – a job that allowed him to save up enough money to buy his very first camera. Following the MoMA exhibition, Penn returned to his young love, and started to draw and paint as a way to reconnect to the creative spirit that fuelled his life’s work in the final decades of his 70-year career.

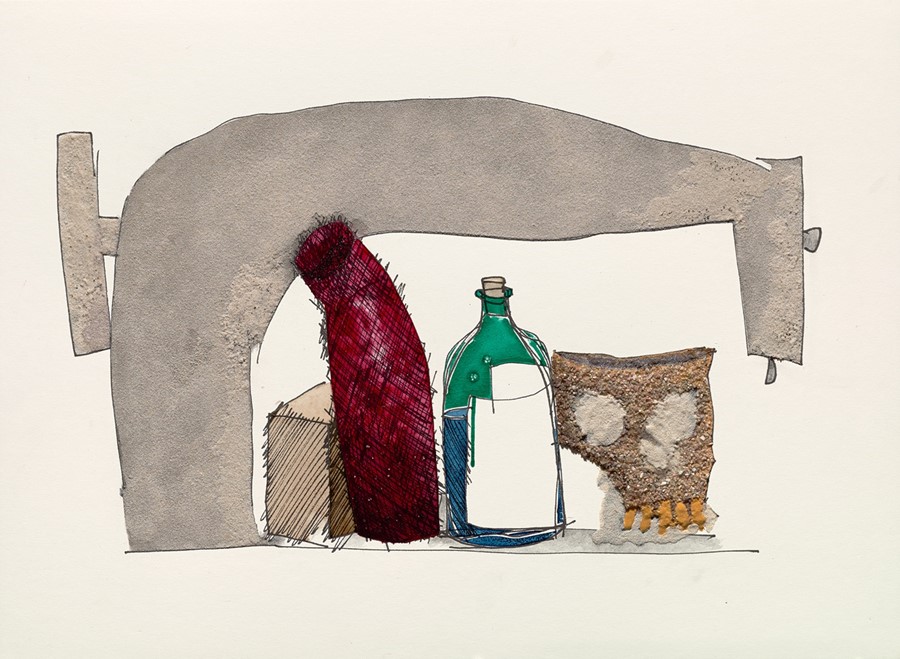

During this late period, Penn’s gift for precision, focus, and clarity became exquisitely lyrical in both his paintings and photographs, which transformed his platonic ideals into deft, rich, and textured visual metaphors and poetry. Now, on the 34th anniversary of the historic MoMA show, a selection of approximately 30 works made between the late 1980s and the early 2000s will be on view at Irving Penn: Paintings at Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York.

“Penn was a guy who got up every morning and went to work. He had no airs about him; he had an extraordinary belief in himself. It was a job that he took very seriously. He generally wore blue jeans, a blue work shirt, and blue Topsider sneakers,” Peter MacGill, president of the gallery, says.

“The energy that went into that exhibition, to dance with the best, was exhausting to him. It drives you to a pinnacle. He didn’t stop photography – I actually think that the best work Penn made was after that show, in the last decades of his life. Just extraordinarily inventive in what he was doing. I think he took refuge from the intensity of what he was doing and going back to his roots in painting.”

Drawing inspiration from the major artistic figures of the 20th century, including Henri Matisse, Giorgio Morandi, and Fernand Léger, Penn’s abstracted works share qualities of character and technique with the photographs, while simultaneously offering a textural layer that film simply cannot. In his final years, Penn became increasingly liberated in his quest to express gesture, line, form and dimension through a delicate blend of mixed media.

Writing in his memoir Passage, Penn reveals: “Pleased with the new freedom, I found inside myself accumulated forms, enjoyed arbitrary color, the touch of the brush, the flow of pigment, the slowness and privacy.”

Although a few of the paintings have been published in his books, “Penn was very guarded about these,” MacGill reveals. Perhaps this is because they provided a sanctuary for Penn to refresh, restore, and renew his spirit.

In a letter dated 1985, his wife, Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn wrote, “He has started to do drawings now, which he enjoys enormously... He works in his studio here in the country every weekend and in town all week... I’m overjoyed to see him in this elated state (creative!) again.”

When Fonssagrives-Penn died in 1992, the paintings once again offered Penn a place to escape, to mediate the tremendous grief that accompanies such a devastating loss after 42 years of marriage.

“I went down the day she died and I hugged him,” MacGill remembers. “He was a very small man, and when I hugged him he said, ‘Please don’t squeeze too hard, the water might come out.’”

Irving Penn: Paintings is at Pace/MacGill, New York from September 13 until October 13, 2018.