There is arguably no greater genre in which human fancy takes flight than that of science fiction, and it’s home to some of the most groundbreaking wordsmiths in the canon of literature

There is arguably no greater genre in which human fancy takes flight than that of science fiction, and it’s home to some of the most groundbreaking wordsmiths in the canon of literature. Relatively recent pioneers such as Arthur C Clarke radically altered our perception of the universe and fearlessly outlined the shape of things to come, acting as a conceptual precursor to the likes of Phillip K Dick, JG Ballard, William Gibson and modern masters such as Lauren Beukes. Whether it’s the battle between man and a psychotic form of alien/artificial intelligence, the evocation of dystopian future worlds or an investigation into the drugged-out paranoid vistas of inner space, the form has absolutely no parallel in terms of imaginative reach. Importantly, it’s also a ‘genre’ with extremely blurred boundaries, and one often delved into by more supposedly more ‘literary’ writers such as Aldous Huxley (Brave New World) or somewhat more recently, Margaret Atwood (The Year Of The Flood). This month, The British Library presents an idiosyncratic exhibition exploring the impact it has had upon our consciousness and the world we inhabit – drawing a line from some of the earliest classical sci-fi stories to the ultra-modern explorations of post-humanism. Here, John-Paul Pryor talks cyborgs, satire and reanimation with curator Andy Sawyer.

Do you thinks some science fiction writers are prescient, in that they attempt to predict the future, and thereby help to actually create it?

I think it is more that they use it as a way of looking at the times they live in. When people write science fiction novels, they are essentially writing about what worries them or what exhilarates them about the present and, in extrapolation, the future. If you look at science fiction writers, from say, the 1950s you could say that their ideas about the future came from an overarching fear of nuclear war, and the hope that we might go into space and find other planets. Of course, there are writers like William Gibson who have kind of created part of the world we live in – his word ‘cyberspace’ provided a good word for a world that didn’t yet exist. It’s true science fiction has done a few things like that.

What kind of things did you want to explore in this exhibition?

I think it was the way science fiction has looked at different ideas: are we alone in the universe? What we are doing to our world? The form establishes an imaginative territory that it then becomes the writers’ job to explore, so that we can look at the future as a sort of default set of ideas based on the present. For instance, this generation of writers are very focused climate change, bioengineering and ideas of post-humanism – this notion that we’ve taken ourselves out of the natural evolutionary path and can now direct our own evolution.

They’re also focused on the sense that it could spiral out of our control…

Yes. In a sense, it’s a very old scientific idea that started in the 1920s – a notion of robots taking over. Now, it’s shifted from robots to artificial intelligence, and the fear is that if we can create artificial intelligence then it will immediately start directing its own evolution much, much quicker than we can. That’s where the idea of technological singularity comes in – the idea that the rate of progress increases to such a point that it’s actually impossible to predict.

What is the earliest from of sci-fi in the show?

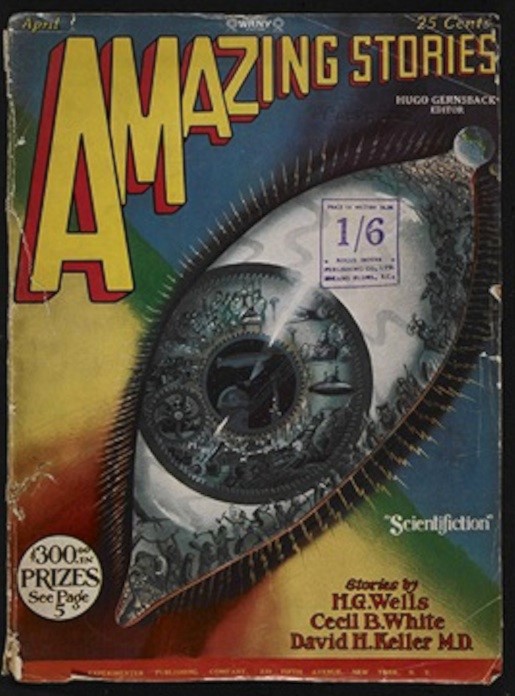

The earliest example that we have was written around 120AD in Ancient Greece and was called True Story. This was the work of a satirist named Lucien who was making fun of folksy travellers tales – people coming back from distant lands saying: "Everything is so different over there… They’ve all got two heads, etcetera." He has his characters taken up to the moon and involved in a fight between the king of the moon and the king of the sun. He was also satirising scientists because there was a lot of scientific speculation at the time about the moon and the nature of the universe. Science fiction has always been a wonderful realm for satire, which is why we also have Jonathan Swift in the show. What is often considered the first science fiction novel is Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, in the sense that the character is using modern speculative ideas of the time about ‘creating life’ with electricity. There were lots of experiments involving channelling electric currents into animal tissue, and the twitch perceived led people to speculate whether electricity was a life force.

A very different kind of inner-space is explored in science fiction much later on…

Absolutely. I think JG Ballard’s early short stories – which were published in science fiction magazines – are underrated because you can really see how he was trying to push the boundaries and switch from stories about outer space to stories about inner space. In the 60s, he moves to the more experimental areas of Crash and Atrocity Exhibition and subsequently moves away from the form, or perhaps even opens it up for the likes of William Burroughs. There was this period in the 1960s when sex, drugs and rock’n'roll pushed science fiction into radical new areas. I mean, in music you had Pink Floyd writing songs like Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun.

Phillip K. Dick is the genre’s most infamous drugged-out writer…

Dick’s a funny example because he certainly was a drug user, but he got very angry when someone once referred to a story of his of having been written under the influence of LSD, which he said was totally not true. Novels like A Scanner Darkly are situated right in the middle of our drug culture, and he employs science fiction to describe the world that he’s actually living in. I just read his biography and he was an extremely complicated person – some would have said he was barking mad, you know? To be honest, yes, he was – in a way – but his post-breakdown novel Valis is incredible. It shows that there’s sanity at work somewhere. He can’t have been absolutely out of it to have penned a novel like that.

Out of this World runs until September 25 at British Library.

Text by John-Paul Pryor