A new exhibition celebrates the work of photographer Martine Franck, wife of Henri Cartier-Bresson, whose intriguing compositions often captured the joy and pain of being a woman

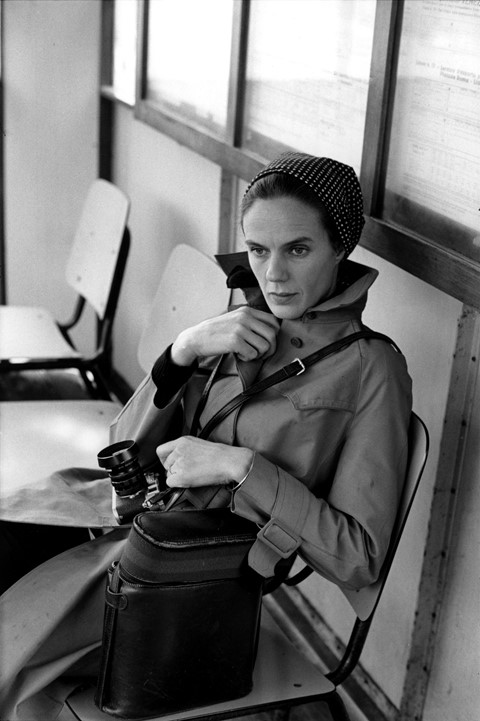

Who? “Taking a portrait of someone,” Martine Franck once noted, “starts with a conversation”. A talented documentary photographer, profile taker, and the wife of Henri Cartier-Bresson, it’s clear that Franck was a skilled conversationalist. Born in Antwerp in 1938, Franck first studied art history at the University of Madrid, before making her way to the École du Louvre in Paris. Here, after some impressive travelling, she began assisting Eliot Elisofon and Gjon Mili at LIFE magazine. The position kick-started a busy freelance career, photographing for the likes of Vogue and The New York Times, and by 1983 she was one of the only women to join the Magnum photo agency.

Franck preferred to work outside a studio, walking the streets and exploring different countries with a 35-millimetre Leica camera clutched in one hand. Filled with her signature black and white film, its spare contrasts left no shadow and no shape unturned. In one of her most famous pictures, dynamic forms are created by a group lounging by a swimming pool in 1976 Le Brusc. The long lines of a tanned body are cradled by a hammock’s criss-cross white netting, the shadow of both like a reflection perfectly replicated on the tiles below. Everything seems calculated down to the crook of white negative space in the arm’s triangular arc as it props up a tired head. Franck had a gift for capturing these natural, unexpected compositions. As she declared, a photograph is “a fleeting, subjective impression”. She remembered for that particular shot “running to get the image while changing the film, quickly closing down the lens as the sunlight was so intense”. Franck loved “the moment that you can’t anticipate: you have to be constantly watching for it, ready to welcome the unexpected”.

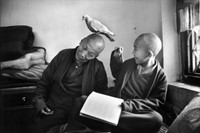

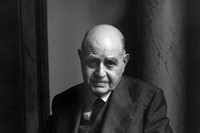

What? It was this attentiveness to the world that enabled Franck to produce such an impressive oeuvre, a selection of which is now on display at the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation. She may be famous for profiling figures such as Marc Chagall or Seamus Heaney, but Franck was always more concerned with documenting the lives of those neglected by the camera’s watchful eye. As one of the only female photojournalists working at the time, and one of the fewer still who earned a place within the renowned Magnum agency, women became a key subject for her.

In one series she titled Professions and Women, Franck gathered together images she’d taken of women in traditionally masculine jobs, from fishermen and locomotive drivers to electricians. Factory workers in Bucharest smile at her camera in stained overalls; Kyoto Geisha girls resist her gaze as they make up their elaborate faces. The range of her work attests to Franck’s true art, and the fact that she was unafraid to capture or converse with anyone. In 1993 she travelled to the “treeless” Tory island just off the Irish coast to photograph the native Gaelic community. One photograph stands out: two young girls caught as they leap off a beach stone wall towards the sand, their faces plastered with glee. These are girls who have yet to be told they cannot. Franck seems to ask, when will this courage – this joy – end? When do the smiles stop? It’s revealing that one of her final projects saw her document another series of young girls, this time in villages in Gujerat, western India, where, rather than jumping off walls, we see girls embroidering their own dowries, literally set to work on their future, stitching together their worth.

Why? “Martine, I want to come and see your contact sheets.” That was Cartier-Bresson’s opening line when he first met Franck in 1966. Despite the 30 years between them the two were married in 1970. Photography was their shared passion, yet Franck admitted she put her husband’s career ahead of her own, and at times her relationship to his success was difficult. A painful example comes from the year in which they were married, when the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London sent out invitations to what was to be Franck’s first solo exhibition which highlighted her husband’s name and his presence at the launch. She promptly cancelled the show. This wide-ranging retrospective of 140 images opens the new Le Marais space at her husband’s foundation, and provides a much-needed space for Franck’s work to stand on its own terms. Franck once noted how she found a language for herself within photography, that it became a means of “telling people what was going on without having to talk”. It’s clear, surveying her work, that a picture says a thousand words.

Martine Franck: A Retrospective runs at the The Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson until February 10, 2019.