A just-opened exhibition in Berlin explores a lesser-seen side of Wojnarowicz’s work, along with photographs and films of him by his fellow artists

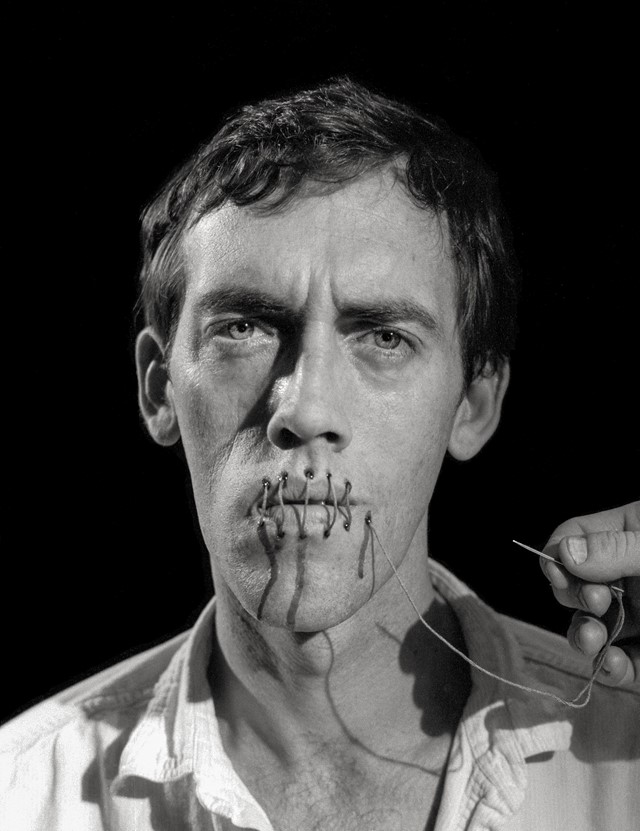

In one of the most striking images of David Wojnarowicz, taken just a few years before he died of AIDS-related illness, the artist, writer and activist is depicted with his mouth sewn shut. The work’s title, Silence = Death, references the slogan from a famous ad campaign started in the mid-1980s which ACT UP, the AIDS activist group Wojnarowicz belonged to, would later adopt as their rallying cry.

This image is one of over 150 works by Wojnarowicz currently on display at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. “The exhibition reflects on Wojnarowicz as a source for both art-making and activism at a time of political and personal uncertainty,” says the show’s curator Krist Gruijthuijsen. “It sheds light on a practice that has been exemplary and inspirational, not only for his contemporaries but also for younger generations, especially in a city such as Berlin.”

Wojnarowicz was a prominent figure in New York’s East Village art scene, and his contemporaries were now well-known figures such as Peter Hujar, Kiki Smith and Nan Goldin. But despite the friendships and collaborations he had with these artists, Wojnarowicz always considered himself outsider and was mistrustful of institutions, including the art world. This feeling came, in part, from his unstable, often violent, childhood which resulted in him dropping out of school at the age of 16 and living on the streets of New York, where he had to hustle in Times Square to be able to survive.

In a chapter dedicated to Wojnarowicz in her book The Lonely City (2016), Olivia Laing reflects on the impact this trauma had on him. “So much of Wojnarowicz’s life was spent trying to escape solitary confinement of one kind or another, to figure a way out of the prison of the self,” she writes. “There were two things he did, two escape routes that he took, both physical, both risky. Art and sex: the act of making images and the act of making love. Sex is everywhere in David’s work, one of the animating forces of his life.”

When Wojnarowicz escaped the streets and started writing and making art in his early 20s, this feeling of isolation was translated into his works. For his first big production, Wojnarowicz photographed his friends wearing masks printed with the face of French poet Arthur Rimbaud. By using the image of Rimbaud, the figures are shown as alienated from the Manhattan and Brooklyn locations they were captured in. In other words, they were as adrift from contemporary American society as Wojnarowicz felt himself to be.

The sex came later, most notably in the form of black-and-white photomontages of gay and straight intercourse, which were known as Sex Series (for Marion Scemama), after Wojnarowicz’s friend and frequent collaborator, and featured pornographic imagery juxtaposed with banal landscapes, in a celebration of sexual desire.

After Wojnarowicz was diagnosed with AIDS, his artwork became more explicitly political. His anger is palpable in a series of images of another masked person: this time sporting a ruff and a baton-shaped nose made of crisp banknotes. Along one side of the nose, the word “culture” is printed in capital letters – a clear rebuke of the money-obsessed art world. The piece also rallies against the stupidity of the culture wars of the 80s and 90s, a debate Wojnarowicz was unwittingly embroiled in when American conservatives took offence at the sexual and religious imagery in his work.

Alongside the exhibition, the gallery has organised a public program featuring readings, film screenings and a discussion on HIV and AIDS today, which aims to bring Wojnarowicz’s activism into the present day. “We are reliving the same period as 1980s where bodies, especially sick bodies, are not taken seriously and are being marginalised,” says Gruijthuijsen. “Wojnarowicz gave the politicisation of the private an entirely new dimension. He used various materials, paintings, performance, film and photography to draw attention to civil rights and gay identity within American popular culture.”

David Wojnarowicz: Photography & Film 1978–1992 runs at KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin, from February 9 – May 5, 2019.