The celebrated multidisciplinary artist Sterling Ruby has long been concerned with freedom. With its degradation, its expression and its preservation – as well as its literal and conceptual importance in the identity of his home and homeland, America. Having grown up in Baltimore and rural Pennsylvania, and then studied in both Chicago and LA, Ruby has drawn from the contours of these variegated US landscapes, compiling a body of work that is equally aesthetically and texturally diverse. What all these environments have in common, though, is an epic scale – rural, urban, industrial – an element that has governed his practice since the start.

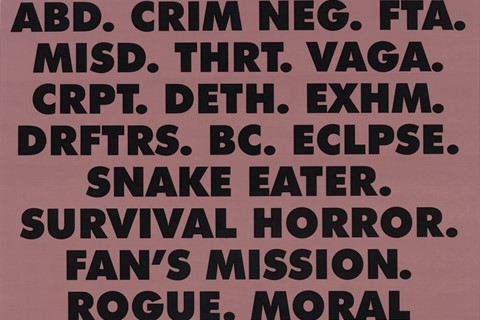

Once described as a “one-man Bauhaus”, Ruby’s output since leaving the Master of Fine Arts programme at Pasadena’s Art Center College of Design in 2005, spans manifold media: ceramics, textiles, collage, drawing, painting, photography, fashion, video, metalwork, sculpture. Breaking open the theory – the gendered attitudes to craft, the art history and minimalism – that framed his education, his works are raw and brutal, explorative of toxic masculinity, devastated by apocalypse. Freewheeling between knurled ceramics, totemic stalagmite sculptures, stuffed vampire teeth emblazoned with the Stars and Stripes, plinths inscribed with scratchiti and the hypnotic surfaces of spray-painted fabrics, Ruby garnered international acclaim. His work is included in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Tate Modern, London; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris. Regardless of the locale, the pieces collected comprise an ongoing treatise exploring the pathological psyche of America today.

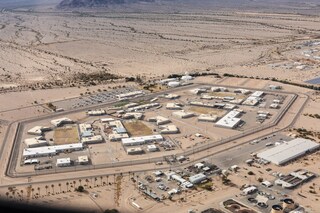

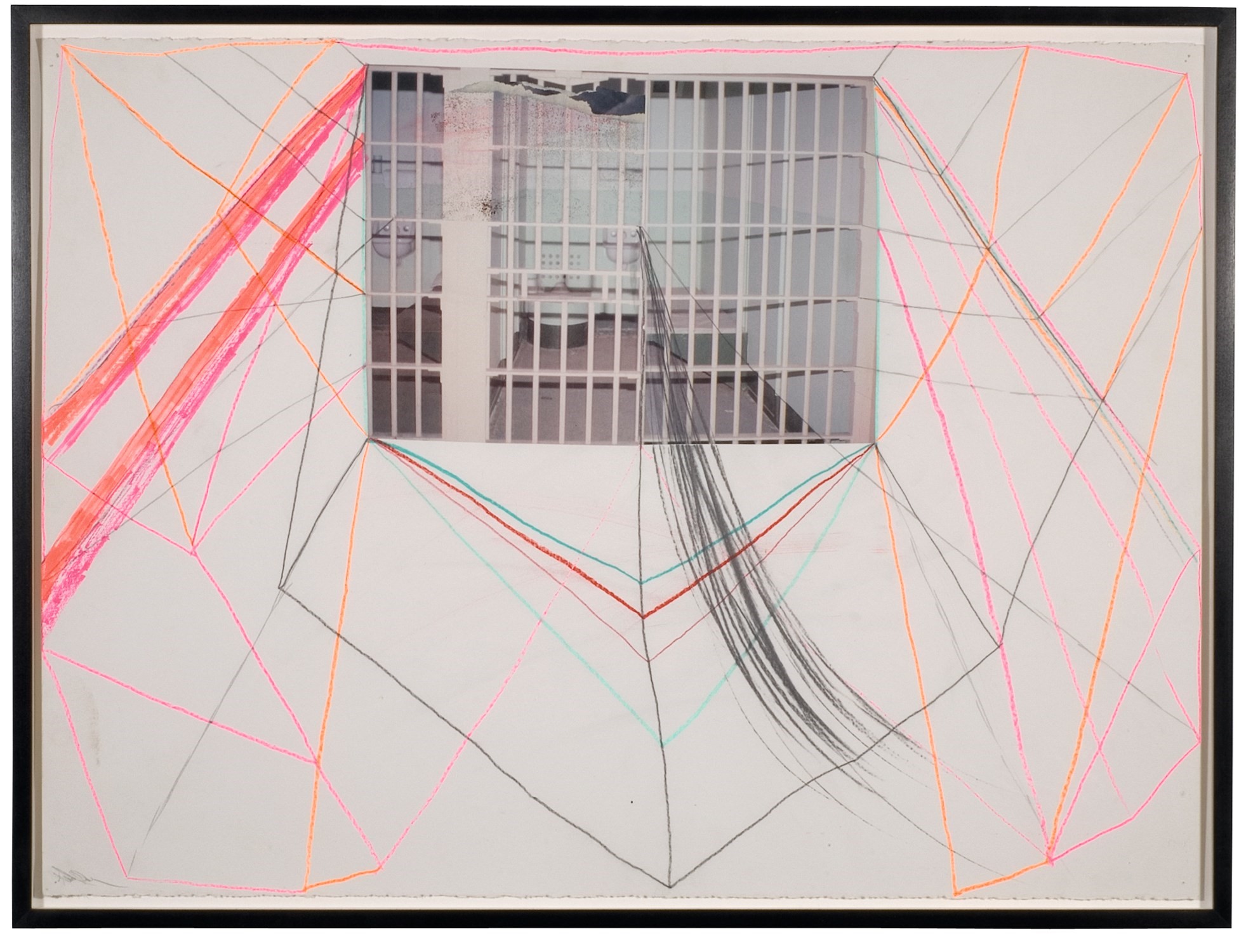

With SUPERMAX, 2005, a show at Marc Foxx Gallery, LA, Ruby first explored the notion of incarceration. “I look at Supermax penitentiaries as being an allegory for a contemporary hell... an inaccessible parallel world,” he once said. “They exist here and now, in America. There is no redemption, only a state of detainment as opposed to correction [...] I also started to think of it in terms of art – where art is and where artists of my generation are. They are largely against the wall with blasted concepts of what art should be, what it could be, what it could never be.” This work was the beginning of a trilogy, which culminated at MOCA in 2008. This year, Ruby returns to the subject matter with DAMNATION, at Sprüth Magers, LA – the result of five years of study and observation, amid political turmoil. Having shot years of aerial footage of California’s adult prisons – there are currently 35 institutions across the state – Ruby presents STATE, a single-channel video projection of this exhaustive and repetitive footage, overlaid with a drum-beat track that eventually slows, in an audible distortion of time. Sweeping over the state’s deserts, farmland and rural landscapes via helicopter, the film shows prisons emerging like ruins of ancient kingdoms or glimmers of future civilisations in a powerful exposure of America’s endless system of incarceration.

Here, the artist discusses that project with architecture critic and curator Mimi Zeiger, who is drawn to topics that subvert typical architectural discourse, and co-curated Dimensions of Citizenship, the US Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. The exhibition interrogated the spatial conditions of design and citizenship, a concept repeatedly undermined today with growing intensity. In conversation, Zeiger and Ruby explore the power and civic responsibility wielded by governments, architects and artists alike, and the collision of the concepts of freedom and justice.

Mimi Zeiger: So, how would you describe DAMNATION in relation to your previous work?

Sterling Ruby: Over the past ten to 15 years, my approach to this topic, and how I wanted to make it part of my art, has changed. I first wanted to get to the core of a kind of repression, and I felt that incarceration was somehow applicable to so many things – the psychological, the societal, the racial. All of these things are at the centre of American history. I wanted my art to somehow excavate repression in that sense. But I also started to understand that I was using the topics from the data abstractly. The artist’s prerogative is to take something from real life and turn it into something akin to poetry. My work doesn’t hinge on strict facts, and it wasn’t ever really about asking the viewer to take a position. But for this project, the abstraction of making art out of painful, real-life things didn’t sit as well with me. I think this project – the aerial shots, quite literally – distanced it from the individual, so it had to be more about the architecture, the objecthood, of these places.

MZ: The idea of repression in relation to the representation of America is interesting, given the trope – the goal of freedom, rights and democracy versus the current political moment. Not only are there those people who are most at risk, those who have been historically oppressed, but new and larger groups of people are being impacted. Do you feel like this current moment has amplified certain areas of your work, or made it more critical to bring politics to the fore?

SR: The anxiety of living in America today is heightened. I also started to become more conscious of the facts. My relationship to activism or political thought and artwork has changed. Art can have a major impact, getting people to think about their positions, or how they empathise with someone. But the problem is that the audience for most contemporary artists like myself already does that. We’re preaching to the converted. I started this project more than five years ago, with almost no objective other than documentation. A lot has changed in that time and, even though it’s hard to grasp the exact data about incarceration, in California there are currently about 130,000 people in state-run prisons, and that’s actually gone down. I started to fantasise about them becoming relics, but of course, that’s completely naive. Over the five years, I started to understand what these institutions could become. We can now conceive a future where the BoP [the Federal Bureau of Prisons] teams up with ICE [US Immigration and Customs Enforcement] to house or to detain. They’re already doing that – there’s Victorville, which is close to LA, where it’s already happening. So I felt strongly I needed to finish this project now, but I still don’t know what it means. I don’t believe that an artist necessarily needs to, or can, take all this data and turn it into a tool for activism. What an artist does is usually something else.

MZ: The question of political art or activist art also resonates within the field of architecture. Can architecture take on certain responsibilities and assert certain positions? With architecture it’s whether or not you build a prison or whether or not you build spaces of incarceration or spaces of torture. There has been pushback against architects who have tried to take on those questions and tried to play with them. There’s not a lot of poetry in the question of incarceration.

What strikes me in your work generally, but from watching the video footage, is that the work is so formal and so abstract it moves in patterns in such an elegant way, but then there’s the movement of a car or you catch a lone prisoner in an orange jumpsuit walking, and suddenly the whole scene changes. Like in your other works where you’re looking at something that is incredibly beautiful and rich and visceral and then you catch the title and the whole piece changes in a moment. I guess it’s not exactly activism but it is something else. I’m not quite sure what term to give it.

SR: Well I’m glad you agreed to this conversation because it opened up a lot of things for me. I, of course, read your Tough Cell [Zeiger’s article Tough Cell, published in The Architectural Review in February 2015, questioned the complicated ethics of whether architects should “curtail their involvement in designing certain spaces associated with prisons, specifically spaces intended for execution and prolonged solitary confinement”. The article explores the 2014 proposal made by Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), which petitioned the American Institute of Architects (AIA) to amend its Code of Ethics and Professional Conduct in order to directly address architecture’s relationship to torture. The AIA responded to the proposal with a refusal, stating that the code “should not exist to create limitations on the practice by AIA members of specific building types”.] article, and I went back to the work because I was never thinking about the architecture firms that made these places. It’s not so clear-cut to just refuse – prisons are going to be built, it’s better that architects with a conscience are at least giving it a thought. I understand some of these firms consulted criminologists and mental-health specialists to try to design less oppressive spaces. That was totally revelatory to me because I just didn’t know what was going on.

MZ: It’s hard to say what is better in some of these situations. Architecture firms that design prisons have whole revenue streams that come from making these kinds of spaces and they do have a full belief that they are helping society through making better, more secure, safer spaces. On the flip side, people argue that architects as humanists, accountable to human-rights ethics, shouldn’t be building these spaces at all. But then that always leads to the question of who, then, will design them? If not the firm, then it’s the engineers at ICE or Homeland Security or the Department of Justice or the correctional department. Someone eventually has to put pen to paper on these.

SR: Ultimately, if there’s no thought, if these spaces are just utilitarian, it’s detrimental.

MZ: I don’t want to make this too biographical, but it struck me that you grew up as a military kid. Military spaces and prison compounds both have a kind of structural logic to them – do you see your interest in prisons coming at all from your personal history?

SR: I grew up in a bunch of locations and was born on an air force base in Bitburg, Germany, and when we came home to the US we moved from Baltimore, a relatively big city, to New Freedom, Pennsylvania, this rural community. At some point later, I realised that I had experienced the urban and the rural. Growing up in Pennsylvania, there were so many industrial-sized farms, the curriculum at the school I went to was essentially about putting students into roles running large farms and large harvesting machinery once they’d graduated. So I understood, or grew up with, space and the logic of systems. I spend five days of every week in my studio in Vernon, California, which is a massive industrialised zone, and the building I have now is on four acres, which in terms of farming isn’t a lot, but in terms of LA, the city, it is.

MZ: The footage is very beautiful but there’s not much beauty in imprisonment…

SR: I kept looking at this footage of these prison buildings and thinking it was less beautiful than it was overwhelming, all-encompassing. You fly over these massive open areas and then all of a sudden, this crazy ghost site appears. I always had a sense of its immensity – how giant and virtual the landscape looked and these giant buildings in them. I became interested in cities that merge rural and urban. I’ve been here in LA for more than 15 years now, but when I first came to LA I felt at ease because it wasn’t a real city, it had its vegetation next to a high-rise, or a massive commercial building would have a three-acre lot next to it that was essentially just plants. I really liked that about LA, so it’s a continuation of that to a certain degree.

MZ: There is this ruderal edge where the landscape and the topography merge with the city. The perimeter that you follow around each of the prisons, is that based on policy? Do you need to stay a certain distance away from a prison? In a way you’re capturing that space of visibility.

SR: The project started when I saw that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) put aerial photography on its website. I was obsessed with the fact that each prison had its own page with its own high-resolution image. I started thinking about the design aspect of these prisons, and how some of them look like faces or skulls, I was curious about their symmetry and where their divisions lie. So, I wanted to film it, I wanted to be up in the air like Robert Smithson, or produce a kind of aerial surveillance that people would recognise. We did some research, and you had to get airspace clearance – out of the 35 state penitentiaries that we shot, only one had a restriction that you couldn’t breach it from a certain distance. And we had to use a helicopter, you couldn’t use a drone, as they are used to drop contraband.

MZ: In this question of aerial photography, we have surveillance – whether or not that’s using satellites, drones or helicopters. Once we start talking about surveillance, I start thinking about Foucault and the Panopticon. [The Panopticon is a type of institutional building designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century. The scheme of the design is to allow all (pan-) inmates of an institution to be observed (-opticon) by a single watchman without being able to tell whether or not they are being watched. The French philosopher Michel Foucault adopted this concept in his text Discipline and Punish (1975), as a metaphor for modern “disciplinary” societies and their pervasive inclination to observe and normalise – the Panopticon therefore operates as a power mechanism.] For me, there was this move from the idea of Bentham’s Panopticon – for policing a prison and the visualisation of that – to making the Panopticon itself visible. With this footage are you suggesting that, in a way, we are policing these images whether we like it or not. Does that resonate at all with you?

SR: I was thinking a lot about aerial photography surveillance, this consideration of sites from above. This was something I was thinking about with my basin ceramic work, and YD [Yard] painting series. Doing this as a video project, I thought aerial videography or photography was so common, particularly when we view areas of conflict. We’re used to having this information presented in this way – war surveillance, footage of ecological devastation. It’s a way to film something that people recognise. Again, it also resonated with me as science fiction, like the trees at the end of Blade Runner, though the Panopticon reference was always going to be present.

MZ: I think there’s a tension there in representing these buildings without the individuals in it. I recently read Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room, which is all about the subjective experience, a nuanced perspective of why people – a woman in this case – end up incarcerated. And I think for people who watch cable TV, [Ruby has previously cited the MSNBC programme Lockup, for which hours of footage are used to document the lives of inmates within the American prison system, as an example of America’s revelry in the system’s own flaws, as well as inspiration for his SUPERMAX series.], or Orange Is the New Black, they begin to understand the idea of prison from the point of view of the individual. The risk in zooming out in this way is, do we lose that individual? Do we lose that story by becoming too far removed and only dealing with the kind of objecthood of these places? Do you feel that tension?

SR: I’ve been listening to prison podcasts that come from a very personal perspective. They’re personal stories, they’re sincere and they give a glimpse of what it’s like on the inside. But I didn’t want to focus in the individual – I wound up believing this project was really about the total perspective of the institutions themselves, and what they might become in the future. I don’t know if as an artist I should spell that out, or if that should be text that’s embedded into the work. I did think about whether I should address the individual experience, but I also understood I couldn’t.

I didn’t take any steps to record the footage during particular hours, but no matter how many different times of day we shot at, we typically wouldn’t see anybody. So, I also started to think that this filming should really be about the object of these buildings and less about the individual. These buildings are created to bury the individual – you just don’t see the prisoners from the outside.

MZ: I get that this then becomes landscape or topography, in the same way that patterns of suburbia became something that we can imagine – cul-de-sacs that are spreading out into world territories, green fields become brown fields – that we are starting to create patterns on the landscape of incarceration. When we were seeing all of the immigrant housing for children along the Texas border and again the aerial shots of the air-conditioned tents, or the satellite imagery in China of Muslim re-education centres growing over time, they have a biological characteristic, growing, changing and fractal-ing. Is it possible to talk about an aesthetic of incarceration? There’s ‘prison orange’, or a term that you used in one of your pieces from a few years ago, ‘institutional minimalism.’ Is this a body of work that can have its own aesthetic?

SR: Maybe. If you make the analogy about minimalist art history, these particular zones or these places of geometry tend to have a hands-off mystique, there is no artist’s hand visible in their production. Judd invented this idea that the forms just appeared, there’s no personality to these objects, no humanity. They are monoliths that you just inspect. Is it the architect’s job to think about these things from a rehabilitative or a mental-health standpoint? Or are these places built in the same utilitarian sense – no hand, no personality, as if they too had just appeared?

MZ: I know that my understanding of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty really changed when I saw the helicopter footage in the show Ends of the Earth: Land Art to 1974, at MOCA a few years ago. It made me re-think how I perceived land art. Now I can’t see it without thinking about the kind of technologies of warfare – of that Cold War headspace – that allowed for this kind of perception to exist.

SR: Right and it’s always been very interesting to look at that art history that really started right around 1968, with the Portapak – for the first time, artists were able to record real-time movement without needing huge film cameras, and politics quickly became embedded in that. If you look at the art from the late Sixties and early Seventies, from this new technology, they were making art that was somehow taking political subject matter and turning it into a repetitive motif. They were distributing it, making copies.

After I left Pennsylvania I went to Chicago and I wound up landing a job at a Video Data Bank at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I started as a secretary and kind of worked my way up to become, I don’t know if you’d call it an editor but somebody who archives and dubs, and it was an amazing education for me, because up to that point I had never really thought about video as art. So, when you look at Smithson and Nancy Holt, all of these artists in the landscape with a camera, who were doing this for the very first time, intervening and transforming the landscape, and then documenting that landscape, there’s so much embedded into it now that is political or historical, but it also reads as science fiction or formalism.

MZ: Is there a sense of exposure? The exhaustive reel of one prison after another, emerging from the landscapes – is it the showing that’s important?

SR: I don’t think that most people can visualise the scale of a penitentiary, but in using video in the same way that the Portapak artists did in the late Sixties, where this aesthetic was being brought to light through the medium itself, hopefully through the repetition – by showing the sheer scale and numbers – it’s very impactful. This is structuralism, using the medium to expose the sheer expanse, the many locations, repeating.

For me, it was just time to finish this project. In thinking about other artists’ works that resonate, and that I always come back to, they all have this existential struggle. Looking at freedom and repression – the balance of those two things, or dealing with the ramification of those things – that to me is the same scenario as artists in the past looking at life and death. I guess maybe that’s a bit of a comparison with looking at life, as a person over time, or even, to be more didactic about it, looking at America. So for me it was really to try to figure out the simplest way to make art – not that it’s simple, but that it’s stripped down. Art can be anything, but in the end it is existentialism, life and death.

DAMNATION will be exhibited at Sprüth Magers, LA, until March 23, 2019.

This story originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2019 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale internationally now.