In the latest instalment of his AnOthermag.com column, Meadham writes about the fashion and portrait photographer

Edward Meadham has a remarkable mind, to which his work as a fashion designer attests. His creations are infused with references to his loves, interests and obsessions – “Beautiful things, craft and subculture,” as he once told us. In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Meadham will write about these obsessions, guiding us through the things that inspire him.

It took until the 1920s for Britain to finally shake off the last echoes of the Victorian era and fully surrender to the trappings that came along with the modern age. Almost 100 years later, the passing of Karl Lagerfeld signalled the death of that old world.

It is only right that every new generation leaves behind its predecessor in order to build their own; it is the natural cycle of cultural evolution. But as someone who has always felt as if they were born in the wrong time, in the wrong body, I could feel myself becoming extinct even in the last century. I cannot help but look upon this encroaching unfamiliarity with the trepidation of a cantankerous old person constantly complaining about how everything was better “in my day”. Which of course it probably was, but also probably wasn’t.

In fashion, the spirit of rawness and urgency have replaced skill and craft, and universality has become more highly prized than considered innovation or a finely honed point of view.

A couple of years ago, I took part in a discussion panel chaired by an over-educated moron who declared that the concept of glamour was outdated, demeaning and irrelevant. While I sit here, contemplating my diminishing desire to continue to exist in a world where talent has become archaic and beauty so passé that they have become ideas so distant that they are to be scorned, I cannot help but think about Cecil Beaton, who dedicated his life to the pursuit of beauty and surrounded himself with people whose every atom of their existence was an expression of their taste.

Few people are so epoch-defining as Cecil Beaton, and it is hard to imagine somebody who seems further removed and more irrelevant to our contemporary world than him. But perhaps inside of this obsolescence there lies a relevance.

As a child, Cecil’s nanny had bought him a Kodak camera and he began to photograph his mother and sisters. Eventually his portrait of the Duchess of Malfi was published by Vogue. Cecil signed an exclusivity contract with Condé Nast, which insured him both a healthy income and the position amongst the circles of society to which he felt he belonged.

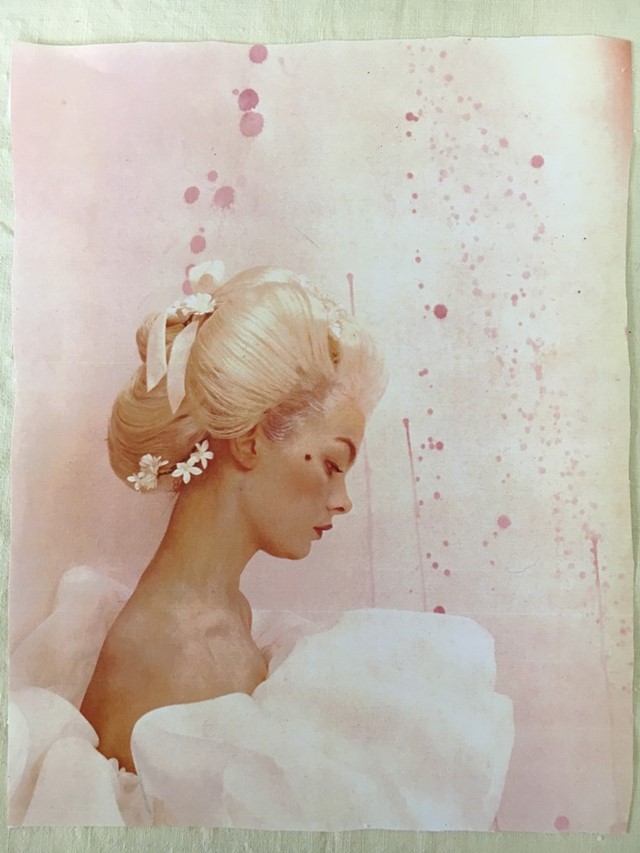

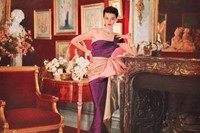

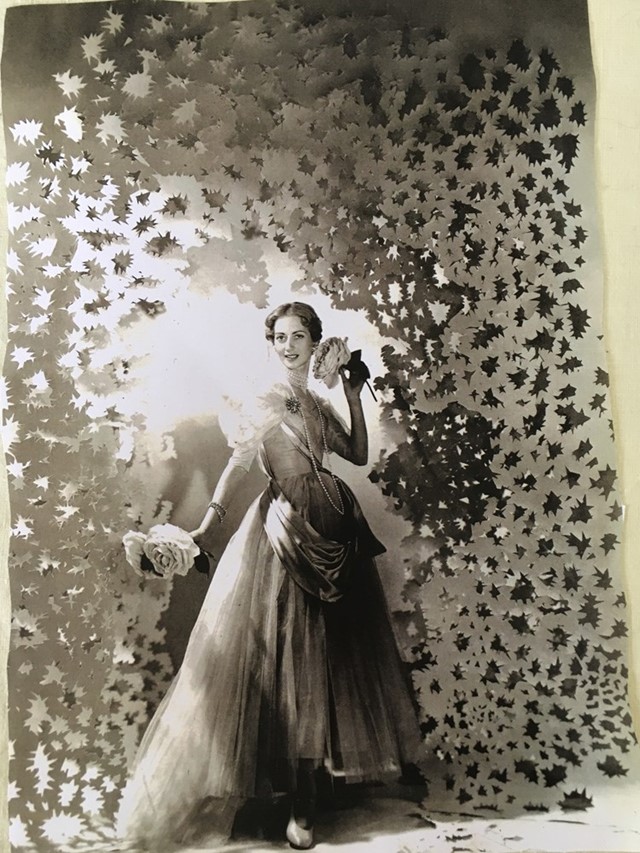

And so, the first of Cecil’s many creative endeavours began, along with the one he is best known for: his black and white portraits. These are an exercise in the drama created between the sitter and the sets, which often comprised carefully lit elaborate arrangements of fishing nets, flowers, plaster busts, torn paper, balloons and cellophane – all resourcefully utilised to the extent of their possibilities to create compositions of poetic beauty and the campest of camp high melodrama.

Cecil photographed everyone in this style: from himself in drag, to Marlene Dietrich, Elsa Schiaparelli, Marilyn Monroe, Coco Chanel, the Royal Family (including her Majesty the Queen’s Coronation portrait) and every member of the English aristocracy in the first half of the 20th century. Notably, his portraits of the tiny aristocratic subculture who were labelled by the press as “the bright young people” – Edith Sitwell, the Mitford sisters, Evelyn Waugh and Stephen Tennant – are a documentation of a short-lived and tiny scene, which to me, although the subjects are of a totally different socio-economic background, are from the same ancestral lineage as Ray Stevenson’s photographs of the Bromley Contingent, in Linda Ashbury’s flat.

Perhaps though, the aspects of Mr Beaton’s life that are more in tune with the modern world lie in that he was a creative multi-disciplinarian and a self-created product of his own imagination. As well as being a highly staged portrait and fashion photographer he also was a photographic documentarian and war photographer, illustrator, Oscar-winning costume designer and stage set designer who published 36 books including memoirs and diaries.

It is one of these books which, above all of Cecil’s other works, is the one which has most delighted and inspired me. The Glass of Fashion is a work to which I have returned over and over again, described as “a personal history of 50 years of changing tastes and the people who have inspired them”. Broken into 18 chapters, the book starts in the very early 20th century and leads us on a journey through a lost world of luxury and delight, unrecognisable from the one we live in today, with a cast of characters including artists, aristocracy, European royalty, actresses and designers, who are vividly described in Mr Beaton’s inimitable flourish of language and accompanied by illustrations from Cecil’s own hand.

Reading The Glass of Fashion offers me respites of escape from this world and transports me back into a time I wish I had been born into instead.